Chapter 1: A brief history of geo-heliocentrism

1.1 Introduction

Perhaps I should start by reminding all readers about the definitions of the three principal configurations of our Solar System proposed (and relentlessly debated) among astronomers throughout the centuries. I will do so in an extremely succint and simplified fashion:

-

GEOCENTRISM: The idea that Earth is at the centre of our Solar System (or of the Universe) and that everything revolves around Earth, including the stars. This is the ancient and long-abandoned Ptolemaic/Aristotelian model. It has been effectively and definitively disproven due to a number of incongruities which came to light as more modern observational instruments became available to astronomers (Venus, for instance, was found to transit closer to Earth than Mercury).

-

HELIOCENTRISM: The idea that the Sun is at the centre of our Solar System and that all our planets (including Earth) revolve around the Sun. This is of course the current, widely accepted configuration (i.e., the Copernican/Keplerian model). It requires Earth to be moving at 90 times the speed of sound (107226 km/h), yet this is an assumption that to this day has never been successfully demonstrated, in spite of countless sophisticated experiments performed over the last few centuries. In this book, it will be further demonstrated that the geometric configuration of the Copernican model presents a number of insurmountable problems. As few people will know, the heliocentric model proposed by Copernicus struggled for several decades to attain recognition among the world’s scientific community due to its many extraordinary and implausible implications. As we shall see, heliocentrism is, quite simply, an untenable theory.

-

GEO-HELIOCENTRISM: The idea that the Earth is at the centre of our Solar System and that all planets except Earth revolve around the Sun. The most renowned geo-heliocentric model is that put forth in 1583 by Tycho Brahe, referred to as the Tychonic system. It is a little-known fact that this model remained the most widely accepted configuration of our Solar System for at least a century after Tycho Brahe’s death in 1601. The subsequently refined yet lesser-known ‘semi-Tychonic’ system (which includes the daily rotation of Earth around its axis) was proposed by Brahe’s trusty assistant Longomontanus in 1622. The latter is generally considered every bit as valid as heliocentrism under all observational respects and is the basis upon which my TYCHOS model is founded. It is still unclear why the semi-Tychonic system was so quickly discarded in favour of the Copernican model since the latter was by no means superior to Longomontanus’ upgraded Tychonic system, as presented in his voluminous “Astronomia Danica”(1622).

Fig.1.1 Tycho Brahe and his assistant Christen Longomontanus (author of the “Astronomia Danica”).

Fig.1.1 Tycho Brahe and his assistant Christen Longomontanus (author of the “Astronomia Danica”).

1.2 Early acceptance of the Tychonic model

In the mid-17th century, the Italian astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli was the most eminent supporter of the Tychonic system. In his main treatise, the 1500-page “Almagestum Novum” (“New Almagest”- 1651), he confronted and assessed the pros and cons of the three above-mentioned models in a fair and objective manner, as most historians will acknowledge. The front cover artwork of his New Almagest shows how Riccioli eventually found the Tychonic model to be ‘weightier’ than the Copernican model.

Interestingly, Riccioli was the first astronomer to describe (in his aforementioned work) the first known pair of double/binary stars, and this some fifty years after Tycho Brahe’s death. Today, however, the astronomy literature generally credits William Herschel with having definitively proven the existence of double stars around the year 1700. In any event, it is beyond dispute that no binary stars were known before the advent of the telescope; hence, in his time, Tycho Brahe was wholly unaware of their existence.

For most of his life, Tycho Brahe apparently believed that Earth was totally stationary, did not rotate around its axis, and that the stars all revolved around it in unison every 24 hours. One can only wonder how Brahe reconciled this belief with the individual proper motions of the stars (all stars move very slowly over time in all imaginable x-y-z directions) which he must have been aware of. Moreover, if the stars all revolved ‘in unison’ around us every 24 hours, their orbital velocities would be quite unthinkably high. Eventually however, as mentioned above, Brahe’s assistant Longomontanus wisely allowed for Earth’s daily rotation around its axis in what became known as the ‘semi-Tychonic’ system. The accuracy of Longomontanus’ refined version of his master’s geo-heliocentric model has not been surpassed to this day:

“Longomontanus, Tycho’s sole disciple, assumed the responsibility and fulfilled both tasks in his voluminous ‘Astronomia Danica’ (1622). Regarded as the testament of Tycho, the work was eagerly received in seventeenth-century astronomical literature. But unlike Tycho’s, his geo-heliocentric model gave the Earth a daily rotation as in the models of Ursus and Roslin, and which is sometimes called the ‘semi-Tychonic’ system. […] Some historians of science claim Kepler’s 1627 ‘Rudolphine Tables’ based on Tycho Brahe’s observations were more accurate than any previous tables. But nobody has ever demonstrated they were more accurate than Longomontanus’s 1622 ‘Danish Astronomy’ tables, also based upon Tycho’s observations.” Christen Sørensen Longomontanus - Wikipedia

However, Longomontanus’ semi-Tychonic system still lacked an explanation for the slow alternation of our pole stars—or what is commonly known as ‘the precession of the equinoxes’; it also proposed a motionless (albeit rotating) Earth, a notion that jars with the fact that all the visible celestial bodies in our skies exhibit some orbital motion of their own.

My proposed TYCHOS model is essentially a natural evolution of the semi-Tychonic system that further refines its unequalled consistency with empirical observation; it provides a long-overdue reassessment and completion of the extraordinary work of Tycho Brahe and Longomontanus which, sadly and inexplicably, was discarded in favour of the Copernican theory – in spite of the latter’s numerous problems and aberrations. As we shall see, these problems stem from the distinctly unphysical nature of its proposed heliocentric geometry. It is a poorly-known fact that the Copernican theory was (justly) rejected for several decades by the world’s scientific community - due the many leaps of logic that its core tenets demanded. One of the most formidable mental efforts required (in order to accept the novel Copernican theory) was the extraordinary dimensions and distances that the stars would have in relation to our system, as illustrated in the following excerpt from “The Case Against Copernicus”:

“Most scientists refused to accept Copernicus’s theory for many decades — even after Galileo made his epochal observations with his telescope. Their objections were not only theological. Observational evidence supported a competing cosmology,the “geo-heliocentrism” of Tycho Brahe. The most devastating argument against the Copernican universe was the star size problem. Rather than give up their theory in the face of seemingly incontrovertible physical evidence, Copernicans were forced to appeal to divine omnipotence.” “The Case Against Copernicus” - by Dennis Danielson and Christopher M. Graney

Another huge problem was, of course, the outrageous implication that our tranquil planet Earth would supposedly be hurtling around space at a breakneck, hypersonic speed of 90 times the speed of sound!

Fig.1.2

Fig.1.2

Caption to above image: “The frontispiece to Riccioli’s Almagestrum Novum tells his perspective on the state of astronomy in 1651. Urania, the winged muse of astronomy, holds up a scale with two competing models, a sun-centered Copernican model, and the Tychonic geo-heliocentric model. Under God’s hand from the top of the image, the scale reports the Tychonic model to be heavier and thus the winner.” New Almagest commentary

1.3 The geo-heliocentric models of Tycho Brahe and Pathani Samanta

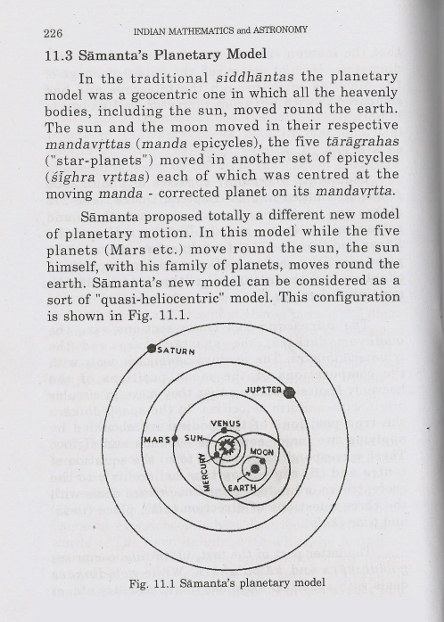

Let us now compare the proposed geo-heliocentric models of arguably the two most proficient naked-eye observational astronomers of all times, Tycho Brahe and Pathani Samanta. Independently of each other, the two astronomers reached practically identical conclusions with regard to the geometric configuration of our Solar System.

Below is a page that I scanned from a book titled “Indian Mathematics and Astronomy”. The book was graciously given to me by its author when I visited him in Bangalore, India, in April 2016: Prof. Balachandra Rao, a now retired professor of mathematics, astronomy historian and author of several captivating books on ancient Indian astronomy. The page features an illustration of the planetary model designed by Pathani Samanta, a man rightly heralded as India’s greatest naked-eye astronomer.

Fig.1.3 A page from the book Indian Mathematics and

Astronomy.

Fig.1.3 A page from the book Indian Mathematics and

Astronomy.

Fig.1.4 The remarkably similar geoheliocentric models of Pathani Samanta and Tycho Brahe

Fig.1.4 The remarkably similar geoheliocentric models of Pathani Samanta and Tycho Brahe

As you can see, the models of these two outstanding celestial observers are virtually identical. I have highlighted (in yellow and red) the intersecting orbits of the Sun and Mars which are clearly consistent with what we would call today a binary pair.

Since Tycho predated Pathani by more than two centuries, one might suspect some plagiarism on the part of the latter. However, it seems to be well-documented that Pathani Samanta (who published a monumental work in Sanskrit, the Sidhanta Darpana) reached his conclusions through his very own observations and ingenuity, working in semi-seclusion and with little or no contact with the Western world for most of his lifetime. I thus find it most unlikely that Samanta simply plagiarized Brahe’s work. Conversely, one could perhaps suspect Brahe of having ‘snatched’ some ideas from another illustrious Indian astronomer/mathematician, namely Nilakantha Somayaji (1444-1544). He predated Brahe by a century or so and was the first to devise a geo-heliocentric system in which all the planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn) orbit the Sun, which in turn orbits the Earth. However, there can be no doubt about the primacy of Brahe’s massive body of astronomical observations and their unprecedented accuracy. So, rather than pursuing this conjecture further, let us instead ask ourselves a more interesting and germane question raised by the above-illustrated identical models of Tycho Brahe and Pathani Samanta:

“How and why did such diverse astronomers, after lifetimes of tireless observations, eventually reach such strikingly similar conclusions, particularly with regard to the intersecting orbits of the Sun and Mars?”

There is probably no easy answer to this question, and we can only marvel at the stunning similarity of their models—something that, to my knowledge, has never been mentioned or discussed in the astronomy literature to this day. In any case, I find it nothing short of shocking that the remarkable lifetime achievements of Pathani Samanta and Tycho Brahe are virtually unknown to the general public today.

Now, if we take a closer look at the illustrations of Brahe’s and Samanta’s models, there is something that intuitively appears to be missing: What geometric component of all the systems observed in our skies is absent from both of the above planetary models?

In my view, this is the major logical flaw in the above models: the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn and the Sun all have circular orbital paths drawn in the model. Only one celestial body is, exceptionally, lacking an orbit: the Earth! Now, why would our planet not have an orbit and thus be motionless, unlike all the celestial bodies in the universe?

As I see it, the idea that the Earth—and Earth only—would remain completely immobile in space is a most unfortunate failure of imagination. Nonetheless, the highest praise and respect goes to these two prodigious astronomers of the pre-telescope era who provided us with the most significant clue of all: namely, that the Sun and Mars are, in fact, ‘interlocked’ in typical intersecting binary orbits, much like the vast majority, or quite possibly all, of the surrounding star systems.

Further on in this book, we shall see how the currently accepted heliocentric model presents a similar logical flaw, namely the notion that our Sun is the only star in our skies lacking a ‘local orbit’ (i.e., a relatively small orbit) of its own. The formidable absurdity of such a claim should be clear to any thinking person. Indeed, the idea that our Sun is the single odd exception to the rule truly challenges plain common sense. Yes, the Sun is believed by mainstream astronomers to have an orbit of its own—not a local orbit, but an orbit around the galaxy. This presumed ‘galactic’ orbit is said to require some 240 million years to be completed!

In the TYCHOS model, of course, the Sun has a small, local orbit of its own which lasts for exactly one solar year. The Sun has a tiny binary companion which we all know by the name of ‘Mars’. Every 2 years or so (more precisely 2.13 y, in our epoch), Mars and the Sun transit at diametrically opposite sides of the Earth: this is what we call ‘the Mars oppositions’, coinciding with Mars’ closest passages to Earth. Yet, to this day, in spite of this peculiar behaviour of Mars (reminiscent of the regular close encounters observed in binary star systems), it seems never to have occurred to modern astronomers that we may live in a binary system. As I shall progressively expound and demonstrate in the following chapters, there is ample evidence that the Sun and Mars make up a binary pair. Along the way, my TYCHOS model will help elucidate and/or resolve a number of persistent cosmological conundrums and quandaries, the existence of which no earnest astronomers or cosmologists can deny.

A fundamental point that the TYCHOS model will demonstrate is that our Solar System is a most remarkably interconnected ‘clockwork’ or ‘gearbox’, the mechanism of which features our Moon as its ‘central driveshaft’ and extends all the way to the outer planets. Yet, modern astronomers have been suggesting that our outer planets are governed by chaos, most likely because they are unaware of the Earth’s own, snail-paced orbital motion which, of course, will ever so slightly ‘upset’ their measurements of the secular motions of the more distant ‘family members’ of our Solar System. Since they are oblivious to the Earth’s true motion in the opposite direction of the other components of the Solar System, they will invoke chaos or some other extravagant concept to explain away what they take for anomalies.

“SOLAR SYSTEM IS CHAOTIC (19 March 1999): Although the stability of planetary motion helped Newton to establish the laws of classical mechanics, new research on the positions of the outer planets suggest they are governed by chaos.” “Solar System is Chaotic” - physicsworld.com

We shall now proceed and take a look at binary star systems. Modern-day astronomers have known for decades that most stars have binary companions which are almost always invisible to the naked eye and very rarely detectable with amateur telescopes. However, despite the continual discovery of new binary systems, the general public remains largely unaware of their existence. One might ask whether those charged with ‘the public understanding of science’ have been doing their job properly.