Chapter 29: EROS & TYCHOS: love at first sight

29.1 The discovery of Eros

“In Greek mythology, Eros is the Greek god of love and sex. His Roman counterpart was Cupid (‘desire’).”

One of my most cherished moments during the course of my ardent TYCHOS research was when I started exploring Eros, a tiny planet or, if you will, near-earth asteroid (NEA). As we shall see, not only does Eros corroborate the TYCHOS model’s tenets, it also demolishes the heliocentric theory of periodic retrograde motion. Firstly though, a summary of the history of the scientific endeavors to measure the distance between the Sun and the Earth is in order.

The discovery of Eros on 13 August 1898 aroused enormous excitement among the leading astronomers of the day. In the preceding decades, much effort had been invested in determining the all-important Earth-Sun distance, which is used today as a unit of length (AU). For example, for the sake of observing the 1874 Venus transit across the solar disk, France, England and the US organized as many as 19 official expeditions around the globe, some of which cost the lives of several sailors and astronomers. “Venus’ 1874 transit” - Wikipedia

Why all these titanic efforts, you may ask. Well, since Venus is the largest celestial body transiting close to Earth, the idea was to measure its parallax in relation to the Sun and thereby determine the exact Earth-Sun distance. In fact, both Mars and Venus had been used for this purpose, but the observations made up to that point were deemed inaccurate. The difficulty of the task is described in an essay by Edmund Ledger titled “The New Planet Eros”, published in 1900:

“It was at one time hoped that this [the Earth-Sun distance] might be accurately determined in the case of Venus by observations made on those rare occasions when it passes in transit across the sun’s disk. But the glare of the sun’s light, the ill-defined edge of the sun’s disk, and the atmosphere of Venus itself, combine to deprive such observations of the necessary accuracy. Apart from some other methods, involving long periods of time and highly complicated theoretical investigations in their use, attention was therefore next given to an attempt to obtain the distance of the planet Mars when it makes its nearest approaches to the earth. It was, however, found to be difficult to measure the exact position of the centre of its disk.” “The New Planet Eros” by Edmund Ledger (1900)

Enter Eros, the first known NEA. When Eros was discovered by German astronomer Carl Gustav Witt at the Berlin Observatory, it was soon realized it would pass much closer to Earth than either Mars or Venus. Two years after its discovery, Edmund Ledger wrote:

“But in the case of Eros we meet with something utterly different and unexpected. A new planet has been discovered whose average distance from the sun is less than that of Mars; a planet which at times comes within a distance from the earth not much more than one third of the nearest distance within which Mars ever approaches it.”

Today, Eros’ closest passages to Earth (~0.17 AU) are estimated to be roughly 2 and 3 times closer than the closest passages of Venus (~0.3 AU) and Mars (~0.45 AU), respectively. Eros is the largest member of a group of NEAs referred to as ‘the Amor asteroids’ . In Latin, ‘amor’ means ‘love’, and ‘Eros’ was the Greek God of love. Why this peculiar nomenclature is interesting will soon become clear.

As I was entering the available data on Eros (orbital size, speed, ephemerides, etc.) into the Tychosium 3D simulator, I noticed that its closest near-Earth passages occur approximately every 81 years and at virtually the same place in the sky. This is somewhat reminiscent of Mars’ 79-year cycle. But when I activated the simulator’s ‘Trace’ function for Eros and pushed ‘play’ my jaw dropped: incredibly, Eros—named after the Greek god of love—traces a huge heart around Mother Earth!

Fig. 29.1 Eros’ closest approach to Earth on 31 January 2012, as traced in the Tychosium 3D simulator. Its peculiar heart-shaped orbit is not a product of any sort of manipulation on my part; it was naturally produced by the simulator as I entered the existing, official astrometric observational data for the famous asteroid (orbital speed, size, period, and computed perigees and apogees).

Fig. 29.1 Eros’ closest approach to Earth on 31 January 2012, as traced in the Tychosium 3D simulator. Its peculiar heart-shaped orbit is not a product of any sort of manipulation on my part; it was naturally produced by the simulator as I entered the existing, official astrometric observational data for the famous asteroid (orbital speed, size, period, and computed perigees and apogees).

I then proceeded to adjust Eros’ closest near-Earth passages in the Tychosium 3D simulator by perusing the data on the JPL/NASA website. Within a few hours of toggling, I was pleased to see an excellent agreement between the Tychosium 3D simulator and the JPL/NASA ephemeride tables for Eros. Table 29.1 provides a back-to-back ephemeride comparison between the JPL and the Tychosium 3D simulator for five very close passages of Eros (1850, 1931, 2012, 2093, 2174). They make for a most spectacular match.

Table 29.1 Comparison between the JPL/NASA simulator and the Tychosium of Eros’ closest passages between 1850 and 2174.

Table 29.1 Comparison between the JPL/NASA simulator and the Tychosium of Eros’ closest passages between 1850 and 2174.

On closer scrutiny, I realized that Eros’ ‘short’ cycle is more precisely 81.1 years. This piqued my curiosity, since 81.1 years is exactly 1/10000 of our Solar System’s ‘mega cycle’ of 811000 years (see Chapters 16 and 20). As may be verified in the Tychosium 3D simulator, Eros will be at almost the exact same place at both ends of any 811000-year period. For example, Eros’ position is virtually the same on 1-06-21 (RA 10h33m and DECL +1°50’) and on 811001-06-21 (RA 10h36m and DECL +1°28’).

At this point, it would be interesting to see how the two Solar System simulators, JPL/NASA and the Tychosium, depict the same super-close passage of Eros. The comparison in Fig. 29.2 should help visualize just why the TYCHOS model, in spite of its radically different geometric configuration, can perfectly account for the observations recorded by astronomers working under the heliocentric paradigm:

Fig. 29.2 A comparison of Eros’ positions (Jan 31, 2012), as of JPL’s simulator and the Tychosium simulator

Fig. 29.2 A comparison of Eros’ positions (Jan 31, 2012), as of JPL’s simulator and the Tychosium simulator

29.2 Eros falsifies the heliocentric theory of retrograde motion

We shall now look at the most ‘mysterious’ aspect of Eros’ observed behavior: the fact that Eros is hardly ever observed to retrograde (reverse direction), unlike all the other planets of our system.

“Unlike most objects in the solar system, Eros never appears to be retrograde (back-track across the sky).” “Eros” - Wikipedia

The above statement from the Wikipedia is not quite correct. As Eros passes closest to Earth, it will indeed back-track by a mere ~20 min of RA on average, and sometimes by as little as 5 min of RA. As you will recall, Copernican astronomers claim the periodic retrograde motions of our planets occur because “Earth overtakes Mars” or “Venus overtakes Earth”, giving the impression that the planets back-track for several weeks. The shifting viewing angle of the planet in relation to the starry background is said to create the optical illusion of a reversal of direction.

However, the observed celestial motions of Eros highlight the glaring problem with this explanation. As we have seen, Eros transits much closer to Earth than Venus. Thus, if retrograde motions were caused by angular shifts, as claimed by the heliocentrists, the nearly imperceptible reversal of Eros would violate the basic laws of parallax and perspective: Eros should be observed to retrograde against the starry background by a much larger amount than Venus. This should become clear by examining Figure 29.3:

Fig. 29.3 Under current theory, Eros should be observed to ‘backtrack’ against the stars for a far larger angular amount than Venus. Instead, the exact opposite is observed. This roundly falsifies the heliocentric theory for retrograde motion.

Fig. 29.3 Under current theory, Eros should be observed to ‘backtrack’ against the stars for a far larger angular amount than Venus. Instead, the exact opposite is observed. This roundly falsifies the heliocentric theory for retrograde motion.

Note that, within the Copernican model, Earth, Venus and Eros are said to have orbital speeds of 30 km/s, 35 km/s and 25 km/s, respectively. The absolute speed differential between Earth and Venus (5 km/s) is the same as the absolute speed differential between Earth and Eros. The fact that Eros hardly retrogrades at all is therefore inexplicable under the Copernican paradigm. So how exactly is Eros observed empirically as it transits closest to Earth? Figure 29.4 shows how astronomers recorded the super-close transit of Eros in the early months of 2012:

Fig. 29.4 Eros’ observed 2012 trajectory (source: Wikipedia)

Fig. 29.4 Eros’ observed 2012 trajectory (source: Wikipedia)

The abrupt, V-shaped retrograde pattern is quite bizarre if viewed within the Copernican framework. How can such a trajectory possibly be reconciled with what is claimed to be a simple, linear ‘overtaking manoeuvre’ on the part of Earth? Surely, something is amiss here. Once more, the Trace function of the Tychosium 3D simulator comes to our aid, showing precisely why Eros is empirically observed to retrograde in a V-shaped pattern:

Fig. 29.5 The Tychosium traces Eros’ peculiar V-shaped retrograde, in full accord with empirical observation.

Fig. 29.5 The Tychosium traces Eros’ peculiar V-shaped retrograde, in full accord with empirical observation.

In conclusion, it is the heart-shaped orbital trajectory of Eros, as predicted by the TYCHOS model, that causes the peculiar, minuscule, V-shaped reversal of Eros. All the planets, comets and NEAs revolving around the Sun appear to obey some magnetic force, as if they were attached to the Sun with a magnetic yo-yo string. It is the length and speed of this ‘string’ that determines the variable shapes of our planets’ orbital, spirographic paths and their variable retrogrades. There is nothing otherworldly about moving bodies being conditioned by a magnetic field: here on Earth, we can make small magnets levitate and, with a little finger push, revolve around a larger ‘mother magnet’, as if attached by invisible strings. Of course, what remains to be understood is just what sort of ethereal force originally set all our universe’s celestial bodies in motion and how they are kept rotating like cogs in a perfect clockwork, century after century.

29.3 The NASA spell

NASA claims to have landed a probe upon Eros back in February 2001, as it found itself at 2 AU (i.e., twice the distance to the Sun). As their story goes, their remote-contolled probe landed just around Valentine’s Day (14 February). They also claim the probe captured some pretty sharp photographs of Eros from a distance of 2590 km (i.e., roughly the distance between Stockholm and Rome). These alleged photographs would have revealed a distinct heart-shaped depression on the suspiciously phallic tip of Eros.

Fig. 29.6 The caption for this NASA image reads: “Just in time for its Valentine’s Day date with 433 Eros, the Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) spacecraft snapped this photo during its approach to the 21-mile-long space rock. Taken on Feb. 11, 2000, from 1609 miles (2590 km) away, the picture reveals a heart-shaped depression about 3 miles (5 km) long. Scientists at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory—which manages the NASA mission—processed the image on Feb. 12. Photos taken from closer in during the next few days will help the NEAR team unravel the mystery of this shadowy feature.” Source: NASA (Image 0125693155)

Fig. 29.6 The caption for this NASA image reads: “Just in time for its Valentine’s Day date with 433 Eros, the Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) spacecraft snapped this photo during its approach to the 21-mile-long space rock. Taken on Feb. 11, 2000, from 1609 miles (2590 km) away, the picture reveals a heart-shaped depression about 3 miles (5 km) long. Scientists at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory—which manages the NASA mission—processed the image on Feb. 12. Photos taken from closer in during the next few days will help the NEAR team unravel the mystery of this shadowy feature.” Source: NASA (Image 0125693155)

NASA fan boys worldwide probably won’t like the TYCHOS, much like children loathe the moment when Santa Claus is revealed to be a fiction instilled in them by their own, trusted parents. Evidently, one of the hardest things for most people to overcome is their emotional attachment to such dreamy and seductive childhood beliefs. The last two or three generations have grown up under the spell of the NASA storytellers’ sagas of wondrous science and Promethean technology, although more and more people around the world are starting to realize that what they are being served is little more than wishful thinking and special effects.

The growing disbelief in NASA’s space-travelling capabilities led the agency to effect a number of structural changes and launch damage control operations with the purpose of ridiculing those who expose the hollywoodesque nature of their exploits and discouraging the general public from any further scrutiny. One such clever operation—generously funded, it would seem—is the Flat Earth Movement, launched around 2015. Successful beyond all expectations, the operation is based on the discredit-by-association (DBA) principle. Scores of seemingly independent ‘grassroot’ videomakers diffuse the silly idea that planet Earth is flat as a pancake while at the same time posing as ‘NASA deniers’. Since the Earth can easily be proved to be spherical, the general public is made to spurn the criticisms and exposés of NASA’s deceptions championed by what they see as ‘kooky, tinfoil-hatted flat earthers’.

29.4 An abiding error

Even Mother Nature herself can sometimes trick our senses, including those of our sharpest minds and observational astronomers. For example, comets are currently believed to move in unphysical ‘cigar-shaped’ orbits due to what was originally a case of mistaken identity: the ‘Great Comet of 1680’ (also called ‘Newton’s comet’) was simply the sighting of the asteroid Eros, not the appearance of a new comet. This fateful gaffe prompted Sir Isaac Newton to formulate the most bizarre theory of his entire career, namely that comets orbit in extremely elongated ellipses, in stark contrast to all other orbital motions.

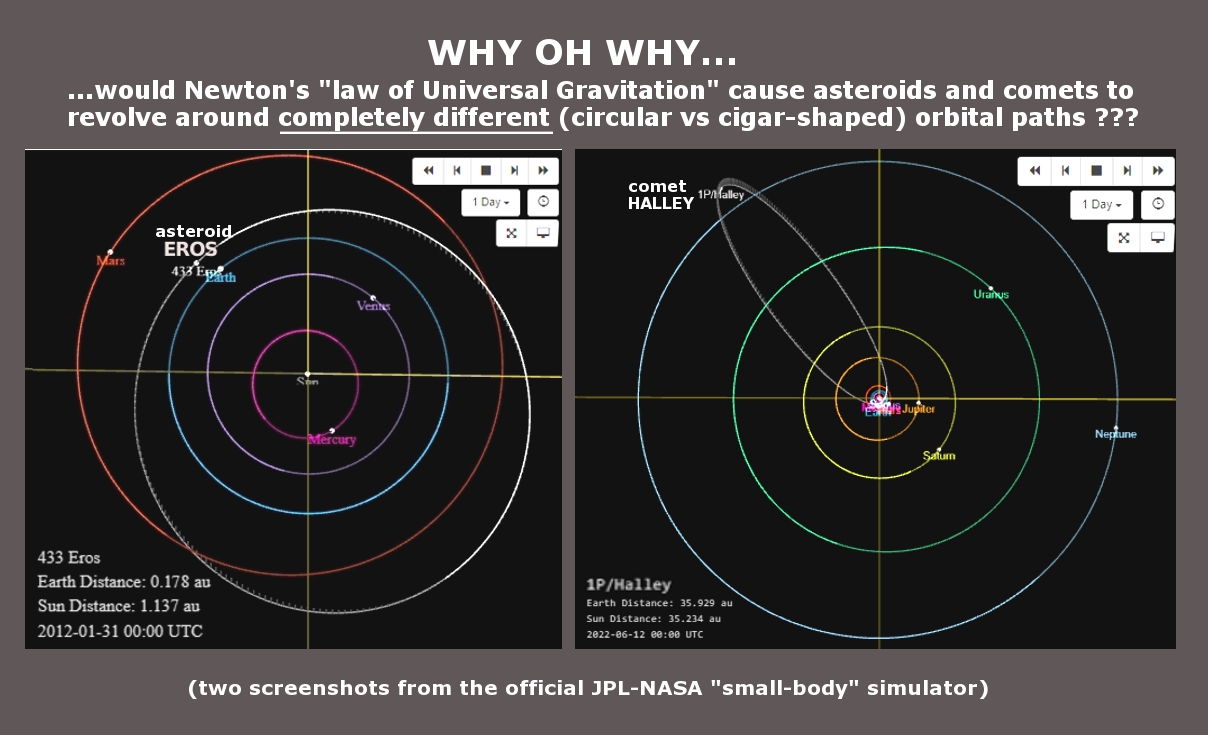

Keep in mind that asteroids and comets can be very similar in size and approach Earth at very similar distances. For instance, Eros measures ~16 km and Halley’s comet measures ~15 km, and both may transit as close to Earth as ~0.1 AU. It is therefore reasonable to ask why asteroids and comets would have wildly different orbital shapes. Aren’t Newton’s ‘laws of universal gravitation’ precisely meant to apply everywhere in the universe? The term ‘universal’ is clearly a misnomer if two types of Earth-grazing celestial objects of similar dimensions obey wholly different physical principles.

Fig. 29.7 The orbital shapes of asteroid Eros and Halley’s comet, according to the JPL/NASA simulator .

Fig. 29.7 The orbital shapes of asteroid Eros and Halley’s comet, according to the JPL/NASA simulator .

Rational thinkers should pause and ask themselves why a universal law of gravity would govern the orbital paths of asteroids and comets in totally different manners. While we wait for the best of our astrophysicists to answer that question, in Chapter 30 we shall meticulously demonstrate that comets do not revolve in ‘cigar-shaped’ orbits, as erroneously concluded by Newton, but have circular (yet trochoidal) trajectories, like all other celestial bodies. The ‘reverse engineering’ of the secular motions of Halley’s comet as recorded (and messed up) by astronomers throughout the ages is a prime example of the explanatory power of the TYCHOS.