Chapter 7: The Copernican model is geometrically impossibile

7.1 Introduction

We have often heard that the heliocentric model and the geocentric model are geometrically equivalent. Some believe they are like the two sides of the same coin, a mere question of perspective and point of view. However, there can only be one correct interpretation of our celestial mechanics and geometry that unfailingly predicts all the interactions between the planets of the solar system and between the planets and the distant stars. Through sound logic, induction and deductive reasoning, we should be able to discard impossible hypotheses and retain that which makes physical, geometrical and optical sense and is backed up by empirical observation.

One such untenable proposition is the Copernican model. Its geometry is not only problematic and questionable, but outright impossible. Indeed, since the model was popularised in the 17th century, scientists like Kepler and Einstein have dreamt up fantastical new laws of nature to save it from bankruptcy. In the following we shall—with a little help from Mars—see how the Copernican model falls apart when exposed to honest scrutiny.

7.2 Cassini’s determination of Mars’ parallax against the stars

Before proceeding, we need to review the famous astronomical enterprise of Giovanni Cassini and his colleague Jean Richer:

“In 1672, [Cassini] sent his colleague Jean Richer to Cayenne, French Guiana, while he himself stayed in Paris. The two made simultaneous observations of Mars and, by computing the parallax, determined its distance from Earth. This allowed for the first time an estimation of the dimensions of the solar system: since the relative ratios of various sun-planet distances were already known from geometry, only a single absolute interplanetary distance was needed to calculate all of the distances.” Giovanni Cassini - Wikipedia

Fig. 7.1 Simple diagram from a French astronomy website illustrating Cassini’s ingenious observational experiment.

Fig. 7.1 Simple diagram from a French astronomy website illustrating Cassini’s ingenious observational experiment.

In short, Cassini and Richer made simultaneous observations of Mars from two earthly locations separated by 7000 kilometers. Using trigonometry, the parallax exhibited by Mars against the starry background made it posssible to determine its distance from Earth.

It is of prime interest to our argument that a mere 7000 kilometers of separation between two earthly observers was enough to cause Mars to be measurably displaced in relation to the firmament, simultaneously aligning with different stars. Now, if for the sake of argument the two astronomers had been separated by hundreds of millions of kilometers on a given day and time, I think we can all agree that the observed parallax would have been considerably larger. As it happens, this one case of missing parallax is all that is needed to disprove the Copernican theory.

7.3 How can Mars return facing the same star in only 546 days?

At certain intervals, Mars conjuncts with the star Deneb Algedi. The following two well-documented successive conjunctions occurred within 546 days:

-

On November 5, 2018 - Mars conjuncted with Deneb Algedi, a binary star located at 21h47min of RA.

-

On May 4, 2020 (i.e. 546 days later) Mars again conjuncted with that same star at 21h47min of RA.

Now, the problem is that, if the Copernican model corresponds to reality, Earth should after 546 days (about 1½ years) find itself on the opposite side of a 300 million km wide orbit around the Sun. This position simply cannot be reconciled with what is depicted by standard 3-D simulators of the heliocentric model.

Before we move on, bear in mind that there are two types of modern Copernican simulators. One attempts to simulate the orbital motions of our planets and moons (examples are the JS Orrery and the Scope planetarium , both of which feature an outer-space 3-D view of the solar system). The other type of planetarium (such as Stellarium and the now defunct Neave planetarium) are far more realistic and verifiable as they simulate our view of the stars and planets from Earth.

Fig. 7.2 Screenshots from the SCOPE and NEAVE planetariums

Fig. 7.2 Screenshots from the SCOPE and NEAVE planetariums

Figure 7.2 compares the positions of Earth and Mars on two given dates separated by 546 days. In this time interval, both Earth and Mars would according to the Copernican model have moved laterally by about 300 Mkm. Yet, on both occasions an earthly observer will see Mars neatly aligned with Deneb Algedi. How can this possibly occur if the Copernican model is true?

In order to put this problem in due perspective, let us take a look at the classic explanation for the observed retrograde motion of Mars. It is said to be due to a parallax effect caused by Earth overtaking Mars. Yet, how can this be reconciled with the fact that Mars can be observed to realign with star Deneb Algedi at points E and A?

Fig. 7.3 Retrograde loops in a Copernican universe

Fig. 7.3 Retrograde loops in a Copernican universe

In fact, and as can be easily verified, Mars can realign with any given star at both ends of a period of about 546 days (∼1.5 solar years). Note that the current discussion about Mars’ parallax in relation to Deneb Algedi, or any given star, is not part of the long-standing and ongoing controversy over stellar parallax. The latter refers to the nigh-undetectable parallax between nearby and distant stars, something we will take a closer look at in Chapter 25.

7.4 Summarising our challenge to the Copernican theory:

The reconjunction of Mars with a given star after both 707 days and 546 days cannot be reconciled with the geometric configuration of the Copernican model, regardless of which laws of nature are invoked.

The TYCHOS model provides a simple and testable explanation for this ‘mysterious’ behaviour of Mars. Over a 15-year period, Mars realigns with a given star 7 times at 707-day intervals, followed by a single conjunction after only 546 days. The shorter period of 546 days is known as Mars’ short empiric sidereal interval (ESI).

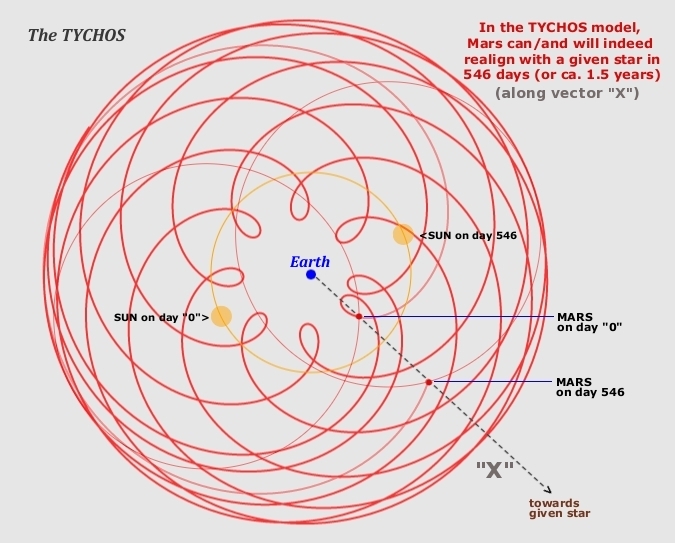

The below diagram shows how Mars can return to the same celestial longitude in only 546 days:

Fig. 7.4 Mars can return to the same celestial longitude after only 546 days.

Fig. 7.4 Mars can return to the same celestial longitude after only 546 days.

The 546-day period occurs when Mars’ spirographic orbital pattern, which has it realigning with a given star every 707 days on 7 successive occasions, ‘skips’ its retrograde loop on the 8th time around. Mars will thus transit across vector ‘X’ earlier than during the previous 7 revolutions. It’s just plain geometry. As we saw in Chapter 5, Mars returns to face a given star in a 15-year cycle, following this rather curious sequence:

Table 7.1

Table 7.1

In short, Mars returns facing the same star at 707-day intervals seven times in a row, followed by a significantly shorter interval of 546 days. So, you may ask, is this what is actually observed? And does the Tychosium 3D simulator confirm this curious behaviour of Mars? The answer to both questions is ‘yes’.

The 15-year Martian cycle. Nine documented conjunctions of Mars with Deneb Algedi between 2005 and 2020:

| 2005-04-22 | |

|---|---|

| +706 days | 2007-03-29 |

| +709 days | 2009-03-07 |

| +710 days | 2011-02-15 |

| +710 days | 2013-01-25 |

| +709 days | 2015-01-04 |

| +707 days | 2016-12-11 |

| +694 days | 2018-11-05 |

| +546 days | 2020-05-04 |

Table 7.2

Fig. 7.5 The Tychosium 3D simulator neatly accounts for each of these 9 transits of Mars at about 21h47m of RA (the celestial longitude of the star Deneb Algedi).

Fig. 7.5 The Tychosium 3D simulator neatly accounts for each of these 9 transits of Mars at about 21h47m of RA (the celestial longitude of the star Deneb Algedi).

In the Tychosium simulator, all these Mars transits occur on the same line of sight towards Deneb Algedi, including the last one which took place on 4 May 2020, only 546 days after the one on 5 November 2018.

Note that no existing simulator of our Solar System (other than the Tychosium) can account for the fact that Mars will cyclically conjunct with a given star as empirically observed, i.e., at the same longitude and in the peculiar pattern of 7 × 707 days and 1 × 546 days. In this respect, the TYCHOS model simply has no rivals; its detractors will have to argue that what the Tychosium simulator maps, traces and demonstrates is just a matter of random coincidence!

In stark contast, the Copernican JS Orrery simulator depicts these same 9 transits of Mars as shown in Figure 7.6. Let us not forget that it was Kepler’s ‘mathemagics’ which allowed the heliocentric model to retain some measure of credibility: by postulating ‘variable orbital speeds’ and ‘elliptical orbits’, Kepler managed to at least make Earth and Mars point in the same general direction in space…

Fig. 7.6

Fig. 7.6

Note that we are not theorising here. All the above Mars-Deneb Algedi conjunctions, as viewed from Earth at 21h47m of RA, did indeed happen—a fact not disputed by any astronomer. So how can the Earth ‘drift sideways’ by about 300 million kilometers and still provide a view of Mars neatly conjuncting with Deneb Algedi? It matters little how far away Deneb Algedi is; what matters is that the much shorter distance between the Earth and Mars would produce a marked parallax if our planet were really scurrying around the Sun in a 300 Mkm wide orbit, as posited by Kepler. Unless you believe the star Deneb Algedi is 300 Mkm across!

Now, Copernican astronomers will tell you that Deneb Algedi is so extraordinarily far away that a lateral displacement of 300 Mkm has no effect on the line of sight towards it. They will also argue that the 9 lines shown in Figure 7.6 may not be perfectly parallel. Regardless, if you choose to side with the Copernicans, you would have to dismiss the perfect juxtaposition of all 9 conjunctions in the Tychosium 3D simulator (in Figure 7.5) as a most spectacular strike of luck. It may be ‘spectacular’, but it would be stretching common sense beyond breaking point to label it a coincidence.

7.5 The extremely rare triple conjunctions of Mars with a given star

In order to verify the accuracy of the Tychosium 3D simulator, I have often used another Copernican solar system simulator, the Star Atlas, for comparison. The Mars-Deneb Algedi conjunctions between 1900 and 2099 shown in Table 7.3 highlight the high level of agreement between the two simulators.

Table 7.3 Mars-Deneb Algedi conjunctions between the years 1900 and 2099

Table 7.3 Mars-Deneb Algedi conjunctions between the years 1900 and 2099

But wait! Something unusual is predicted to happen in the year 2050: a triple conjunction of Mars with Deneb Algedi within a 117-day time frame. How could such a triple conjunction possibly occur in the Copernican model? And if it is true that Mars gets ‘overtaken’ by Earth every 2.13 years or so, why wouldn’t such triple conjunctions be observed each and every time Earth ‘overtakes’ Mars? The Copernican model offers no rational explanation for this, but the Tychosium 3D simulator promptly comes to our aid: In 2050, Mars’ retrograde loop will be almost perfectly centered around the line-of-sight vector joining Earth and Deneb Algedi. This will cause Mars to conjunct with that star on three occasions (A, B and C) within only 117 days.

Figure 7.7 The three conjunctions as displayed in the Tychosium 3D simulator. As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Figure 7.7 The three conjunctions as displayed in the Tychosium 3D simulator. As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words.

Simply put, in 2050 Mars will be retrograding in the line of sight of Deneb Algedi, resulting in three conjunctions within less than 4 months. You can and should verify all this by yourself by perusing the Tychosium 3D simulator. The more curious and inquisitive readers may then wish to open the Copernican JS Orrery simulator on their laptops and visualize how it pretends to depict the expected triple Mars-Deneb Algedi conjunction of 2050 (on the three dates listed in Figure 7.7). I trust that, following this little exercise, the reader will find the title of this chapter a bit less pompous and extravagant than it may seem at first sight.

Even though the TYCHOS model—what with its ‘spirographic’, trochoidal orbits— may be initially perceived as a more complex system than the visually plain and pleasing ‘Copernican carousel’, it ultimately provides far simpler and logical answers to the motions of our Solar System as observed throughout the centuries. In the good tradition of the proverbial Occam’s razor problem-solving principle, the TYCHOS model does away with all the unnecessary, contrived and aleatory factors (‘perturbations’, ‘turbulences’, ‘gravitational & non-gravitational effects’, etc.) dreamed up by the heliocentrists in order to try and justify the many inconsistencies and aberrations afflicting their ‘long-established’ theory.

Having said that, I fully realize that—at such an early stage of this book—the reader will still have many more questions regarding the core principles of the TYCHOS model. All I can say is: read on.

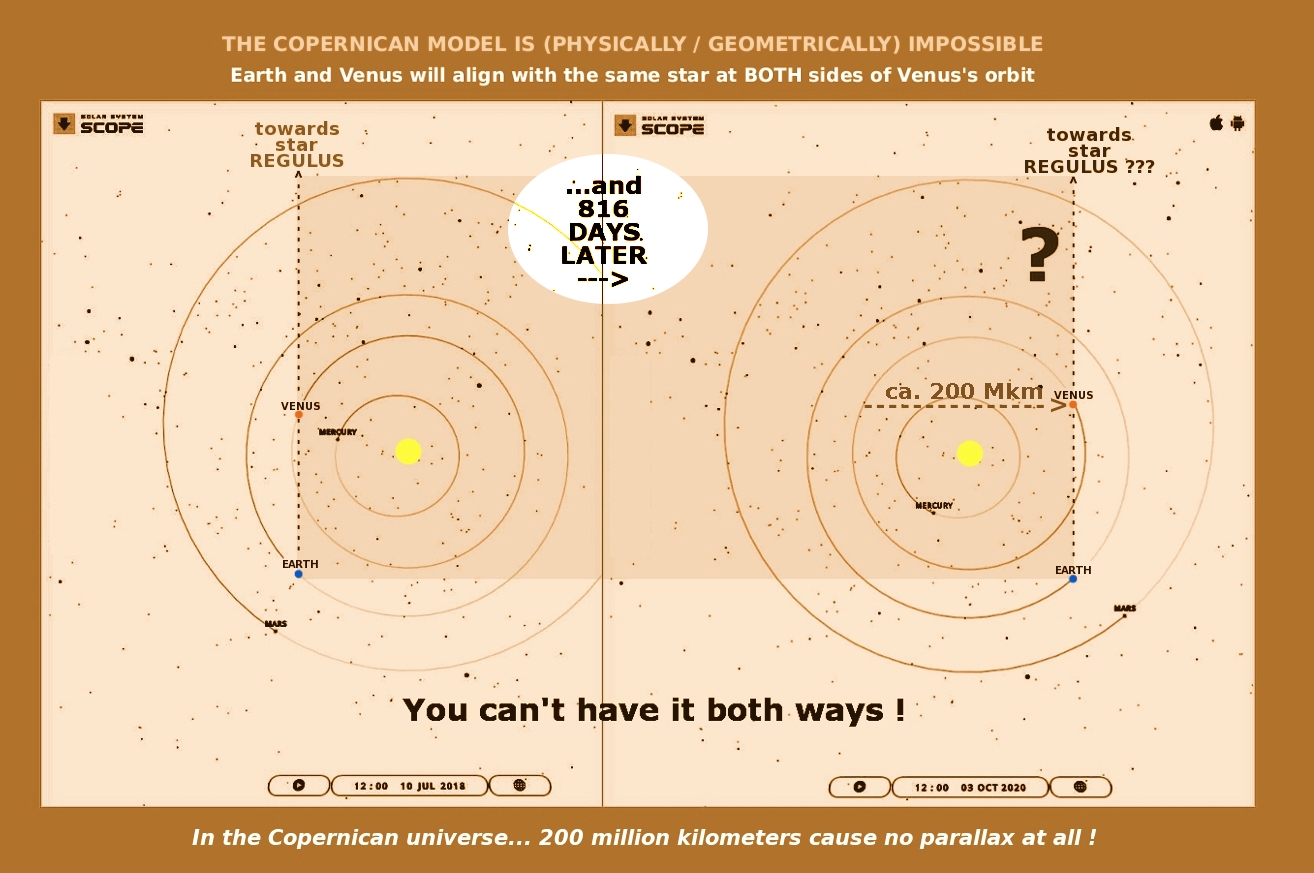

7.6 The impossible 816-day reconjunction of Earth and Venus with a given star

We shall now take a look at Venus by comparing two screenshots from the Scope planetarium depicting two conjunctions of Earth and Venus with the star Regulus in the constellation Leo at an interval of 816 days (or 2.234 years). During that period, according to the Copernican model, Earth and Venus would both be displaced laterally (i.e., perpendicularly to Regulus’ location) by about 200 million km. Yet, Venus was actually observed to conjunct with Regulus on both these dates (2018-07-10 and 2020-10-03). Just as the Copernican model fails to explain the full cycle of Mars-Deneb Algedi conjunctions, it is at a loss to account for the alignment of Venus and Regulus, as empirically observed in 2018 and 2020.

Fig. 7.8 Two screenshots from the SCOPE planetarium. Earth and Venus will align with the same star at both sides of Venus’ orbit.

Fig. 7.8 Two screenshots from the SCOPE planetarium. Earth and Venus will align with the same star at both sides of Venus’ orbit.

Again, Copernican astronomers will claim that Regulus is so immensely distant that the lines of sight towards Venus and Regulus are not totally parallel, but will somehow ultimately converge towards Regulus. Now, we may debate this question of parallelism until the cows come home, but the fact remains: Venus did indeed conjunct with Regulus on those two dates, as documented by astronomers.

The NEAVE planetarium, which realistically simulates the firmament as observed from Earth, confirms that Venus and Regulus did indeed conjunct on both 10 July 2018 and 3 October 2020, 816 days apart:

Fig. 7.9 Two screenshots from the NEAVE planetarium showing what actually was observed from Earth.

Fig. 7.9 Two screenshots from the NEAVE planetarium showing what actually was observed from Earth.

The Tychosium 3D simulator shows why Venus can and will return facing a given star in 816 days:

Fig. 7.10 Two superimposed screenshots from the Tychosium 3D simulator.

Fig. 7.10 Two superimposed screenshots from the Tychosium 3D simulator.

The TYCHOS model clearly accounts for Venus’ physical return to the same celestial longitude after an 816-day interval to reconjunct with the star Regulus, whereas the Copernican configuration plainly contradicts empirical observation.

→ In the Copernican model, Venus conjuncts with the star Regulus every 816 days, but Earth and Venus are also said to travel ‘sideways’ for about 200 million km during the same period—enough to create a measurable parallax.

→ In the TYCHOS model, Venus conjuncts with the star Regulus every 816 days simply because it physically returns to that same celestial longitude. No parallax. No ‘mystery’ to explain away.

Next, we shall take a closer look at the Sun’s two moons, Venus and Mercury. Referring to Venus and Mercury as lunar satellites may sound beyond heretical, but the compelling and easily verifiable facts presented in Chapter 8 leave no room for doubt.