Chapter 26: Probing Kapteyn, Hubble and Esclangon

26.1 Kapteyn, my Kapteyn!

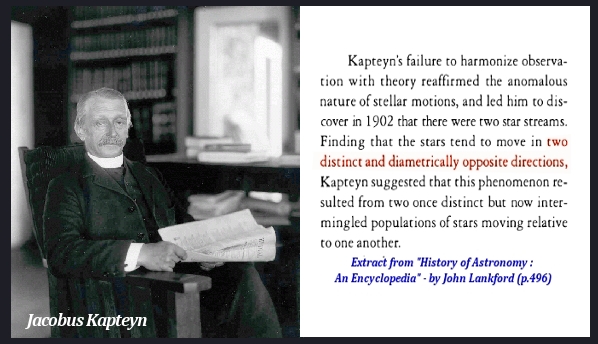

Over the past century, a number of remarkable discoveries by highly competent astronomers have been solemnly ignored by the scientific community for reasons that should become clear as we take a look at the thorough investigations of Jacobus Kapteyn, Edwin Hubble and Ernest Esclangon. When viewed through the lens of the TYCHOS model, the true significance of their findings comes to light and their work can readily be retrieved from the dustbin of history to which it has been unjustly consigned. Let us begin with Jacobus Cornelius Kapteyn and how he interpreted the vexing issue of negative stellar parallax:

“Jacobus Cornelius Kapteyn, (born Jan. 19, 1851, Barneveld, Neth. — died June 18, 1922, Amsterdam), Dutch astronomer who used photography and statistical methods in determining the motions and distribution of stars. While recording the motions of many stars, he discovered the phenomenon of star streaming — i.e., that the peculiar motions (motions of individual stars relative to the mean motions of their neighbours) of stars are not random but are grouped around two opposite, preferred directions in space.” “Jacobus Kapteyn” - Britannica

Fig. 26.1 Jacobus Kapteyn / Fig. 26.2 Extract from “History of Astronomy : An Encyclopedia”, by J. Lankford

Fig. 26.1 Jacobus Kapteyn / Fig. 26.2 Extract from “History of Astronomy : An Encyclopedia”, by J. Lankford

Jacobus Kapteyn’s conspicuously short Wikipedia entry contains the following summary of his work:

“In 1904, studying the proper motions of stars, Kapteyn reported that these were not random, as it was believed in that time; stars could be divided into two streams, moving in nearly opposite directions. In 1906, Kapteyn launched a plan for a major study of the distribution of stars in the Galaxy, using counts of stars in different directions. The plan involved measuring the apparent magnitude, spectral type, radial velocity, and proper motion of stars in 206 zones. This enormous project was the first coordinated statistical analysis in astronomy and involved the cooperation of over forty different observatories.” “Jacobus Kapteyn” - Wikipedia

I feel compelled to express my warmest gratitude for the stellar work of Jacobus Kapteyn whose gargantuan lifetime efforts were largely neglected and misunderstood, much like those of Dayton Miller and Tycho Brahe. If Kapteyn were still alive today, he would have been my first choice of peer reviewer for the TYCHOS model. In his day, he was considered the world’s foremost expert in stellar motions and distributions due to his rigorous and exhaustive statistical surveys. His “Plan of Selected Areas” involved a multitude of observatories worldwide focusing on selected stellar regions, and his astronomy laboratory was well harnessed for the analysis and synthesis of the collected data. His American colleague and friend Frederick H. Seares famously stated that:

“Kapteyn presented the figure of an astronomer without a telescope. More accurately, all the telescopes of the world were his.”

In other words, Jacobus Kapteyn had at his disposal a unique wealth of observational data, such as no past or present astronomer could ever dream of. So what exactly did Kapteyn ultimately conclude after decades of methodical studies of the stellar motions? Well, he found that the stars tend to move in two distinct and diametrically opposed directions, a phenomenon he dubbed ‘star-streaming’.

Fig. 26.3 Extract from “A History of Astronomy: from 1890 to the Present”, by David Leverington.

Fig. 26.3 Extract from “A History of Astronomy: from 1890 to the Present”, by David Leverington.

Kapteyn’s discovery obviously caused great astonishment and controversy in the global scientific community, but at the time no one (including Kapteyn himself) was able to grasp the world-shattering, ‘Copernicidal’ implications of his findings.

“The well-known Dutch astronomer, Professor Kapteyn, of Groningen, has lately reached the astonishing conclusion that a great part of the visible universe is occupied by two vast streams of stars travelling in opposite directions.” “Astronomy of To-Day” - by Cecil G. Dolmage (1910)

Conclusion reached by Jacobus Kapteyn after decades of painstaking study:

“There are two vast streams of stars travelling in opposite directions.”

Fig. 26.4 Extract from “Kapteyn and Statistical Astronomy” - by Erich Robert Paul (1985)

Fig. 26.4 Extract from “Kapteyn and Statistical Astronomy” - by Erich Robert Paul (1985)

So what could possibly have led Professor Kapteyn to reach such an astonishing conclusion? And did he submit a theory or justification for the existence of these “two vast streams of stars travelling in opposite directions”? Unfortunately not. In the absence of a rational explanation of his findings, Kapteyn’s lifetime work became easy prey for the gatekeepers of the Copernican belief system. As one might have expected, his work was promptly attacked and ‘discredited’, especially by a bizarre character by the name of Harlow Shapley.

26.2 The TYCHOS elucidates Kapteyn’s ‘star streaming’

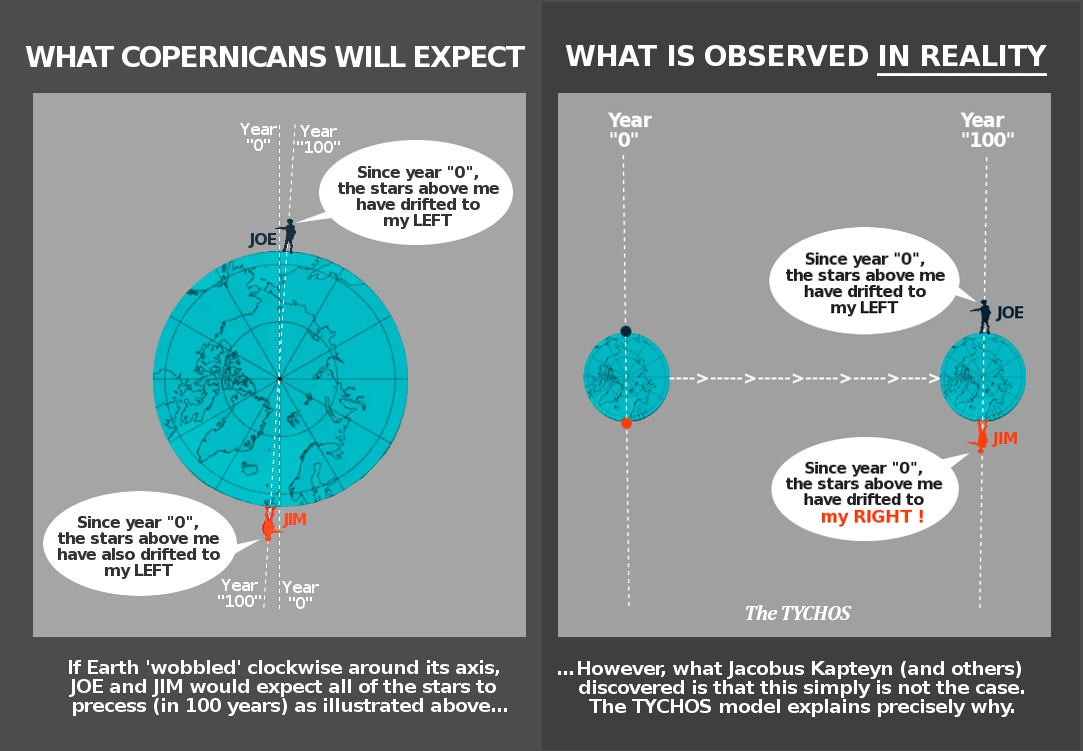

We shall now see how the TYCHOS model can readily account for what came to be known as ‘Kapteyn’s Universe’. Like so many other conundrums elucidated in this book, the ‘star streaming’ effect derives from Earth’s slow motion around its PVP orbit, something Jacobus Kapteyn, himself a Copernican devotee, could not have been aware of. The diagram in Figure 26.5 compares the stellar motions expected by the Copernican model with those actually observed and predicted by the TYCHOS model. It is crucial to understand the fundamental difference between the two scenarios, so please analyze them attentively.

Fig. 26.5 Note: both Joe and Jim are depicted as standing with their backs facing the viewer and looking at stars located above their respective southern horizons.

Fig. 26.5 Note: both Joe and Jim are depicted as standing with their backs facing the viewer and looking at stars located above their respective southern horizons.

We saw in Chapter 10 that the General Precession is not caused by a fanciful ‘wobble’ of Earth’s polar axis, but simply by the Earth’s motion around its PVP orbit, which in short time periods may appear like a virtually straight line, especially if you are unaware of it. A Copernican astronomer might therefore conclude that there are two distinct streams of stars moving in opposite directions. In fact, this is precisely what Jacobus Kapteyn did.

Now, as you may recall, Chapter 23 quotes various astronomy papers regarding the speed of our solar system relative to the ‘fixed stars’. Initially estimated at approximately 20 km/s, more recent testing has refined the value to 19.4 km/s (69840 km/h). By dividing 69840 km/h by the TYCHOS reduction factor (42633) we obtain ~1.638 km/h, which is nearly identical to Earth’s orbital speed of 1.601669 km/h, as proposed by the TYCHOS model. Kapteyn also had a word or two to say about the speed of ‘stellar displacement’:

“Kapteyn continued with the more literal interpretation in constructing his Universe and interpreted the two streams as two systems rotating in opposite directions. The velocity of the two streams would be around 20 km/s, but in opposite directions.” “The Legacy of J.C. Kapteyn” by Piet C. van der Kruit and Klaas van Berkel

One couldn’t wish for a better confirmation of the core concept illustrated in Figure 26.5, showing how Joe and Jim will see the stars moving in opposite directions. Evidently, Kapteyn’s statistical analyses of the observed motions of our surrounding stars yielded precisely what is predicted by the TYCHOS model. Of course, his two opposite ‘star streams’ are an optical illusion, yet his unjustly sidelined work can now finally be vindicated by the TYCHOS model. But to truly reinstate Kapteyn as one of the foremost astronomers of the early 20th century, we need to take a good look at the shady character who ‘discredited’ his inconvenient ‘star streaming’ theory.

26.3 About Harlow Shapley, Kapteyn’s ‘hangman’

Who exactly was this fellow who almost seems to have been commissioned to disenfranchise Jacobus Kapteyn? Let us start by reading from the entry for Harlow Shapley on the Wikipedia:

“Harlow Shapley (November 2, 1885 – October 20, 1972) was a 20th-century American scientist, head of the Harvard College Observatory (1921–1952), and political activist during the latter New Deal and Fair Deal. He used RR Lyrae stars to correctly estimate the size of the Milky Way Galaxy and the Sun’s position within it by using parallax. Shapley was born on a farm in Nashville, Missouri, to Willis and Sarah (née Stowell) Shapley, and dropped out of school with only the equivalent of a fifth-grade education. After studying at home and covering crime stories as a newspaper reporter, Shapley returned to complete a six-year high school program in only two years, graduating as class valedictorian. In 1907, Shapley went to study journalism at the University of Missouri. When he learned that the opening of the School of Journalism had been postponed for a year, he decided to study the first subject he came across in the course directory. Rejecting Archaeology, which Shapley later explained he couldn’t pronounce, he chose the next subject, Astronomy.” “Harlow Shapley” - Wikipedia

Remarkably enough, our failed-journalist-turned-astronomer eventually managed to make a name for himself at the highest levels of astronomy—and politics. Here he is, happy as a clam, being received in the Oval Office by none other than President Roosevelt:

Fig. 26.6 Members of the Independent Voters Committee of the Arts and Sciences for Roosevelt visit FDR at the White House (October 1944). From left: Van Wyck Brooks, Hannah Dorner, Jo Davidson, Jan Kiepura, Joseph Cotten, Dorothy Gish, Harlow Shapley.

Fig. 26.6 Members of the Independent Voters Committee of the Arts and Sciences for Roosevelt visit FDR at the White House (October 1944). From left: Van Wyck Brooks, Hannah Dorner, Jo Davidson, Jan Kiepura, Joseph Cotten, Dorothy Gish, Harlow Shapley.

Shapley is reported to have pronounced the following words in a speech at the American Association of Science in Boston, to which he was elected president: “Of the five worst enemies of mankind, the ‘genius maniac’ is the most potent killer”. He then suggested that “genius could be controlled by killing off, in infancy, all primates showing evidence or promise of genius, or even talent”.

Fig. 26.7

Fig. 26.7

This dubious individual then went on to denigrate Kapteyn’s discoveries basically by claiming the Milky Way is far larger than previously imagined. At the time, Shapley was assisted by a team of theoretical astrophysicists who came up with purely conjectural ideas (‘stellar speed differentials around the galactic center’, or something to that effect) to explain why some stars are seen to move in the opposite direction of other stars. In fact, it appears that we have to ‘thank’ Shapley for having further inflated the size of our galaxy and further belittled the ‘cosmo-philosophical significance’ of Carl Sagan’s paltry ‘pale blue dot’. The credibility deceptively attributed to Shapley’s claims was instrumental in sweeping Kapteyn’s threatening ‘star streaming’ theory under the rug, once more postponing the inevitable demise of heliocentrism.

26.4 The ‘assault’ on the notion that all stars are binaries

There was, however, an even greater menace jeopardizing the heliocentric world view, namely the notion that all stars are locked in binary systems. As should now be crystal clear to the reader, if it should eventually emerge that all stars—without exception—have one or more binary companions, heliocentrism will be toast. As mentioned in Chapter 3, it was Jacobus Kapteyn who famously stated that:

“…if all stars were binaries there would be no need to invoke ‘dark matter’ in the Universe.”

Once again, the devious Harlow Shapley led the assault on the growing evidence pointing to the very distinct possibility that all star systems are binaries. The circumstances of this other effort by Shapley to salvage heliocentrism are recounted in a book by John B. Hearnshaw titled “Analysis of Starlight: Two Centuries of Astronomical Spectroscopy” (1990). At the beginning of the 20th century, a heated debate had broken out concerning the so-called ‘Cepheid variables’:

“A Cepheid variable is a type of star that pulsates radially, varying in both diameter and temperature and producing changes in brightness with a well-defined stable period and amplitude. The number of similar variables grew to several dozen by the end of the 19th century, and they were referred to as a class as Cepheids.” “Cepheid variable” - Wikipedia

‘Cepheids’ are claimed to heftily grow and shrink periodically in the form of ‘radial pulsations’ and most Cepheids are said to be hundreds or thousands of light years away. If the stellar distances calculated by heliocentrists were anything near realistic, this would rule out the possibility that these ‘Cepheids’ are simply binary stars periodically eclipsing each other as they revolve in intersecting orbits. Why? Because they would have to be orbiting at utterly implausible speeds. Hearnshaw’s book also documents the fact that it was Shapley who first suggested to completely abandon the idea that Cepheids were simply binary stars.

Fig. 26.8 Extract from “Analysis of Starlight” - by John B. Hearnshaw

Fig. 26.8 Extract from “Analysis of Starlight” - by John B. Hearnshaw

In the abstract of his 1914 paper titled “Of the Nature and Cause of Cepheid variation”, Shapley made his intentions clear—albeit disguised under a disingenuous ‘appeal to investigate the question’:

“The purpose of the present discussion is to investigate the question of whether or not we should abandon the usually accepted double-star interpretation of Cepheid variation.”

Eventually, none other than Sir Arthur Eddington—the man who propelled Einstein to universal stardom—joined the fray in support of Shapley’s novel and bizarre thesis that Cepheids were not eclipsing binaries, but rather some sort of ‘pulsating staroids’ that somehow grew physically larger and smaller at regular intervals. To be sure, neither Eddington nor Shapley ever explained just what kind of exotic physics would cause such stars to dramatically shrink and grow, yet their weird ‘Cepheid variable’ concept was eventually embraced by most astrophysicists around the world. The few researchers who argued against it, providing data showing that ‘Cepheids’ could very well be eclipsing binaries, were cold-shouldered.

Another tell-tale extract from Hearnshaw’s book shows that Eddington was standing on thin ice in his defense of Shapley and that his ideas about the nature of ‘Cepheids’ were vigorously rejected by a number of his international peers:

Fig. 26.9 Extract from “Analysis of starlight”, by John B. Hearnshaw

Fig. 26.9 Extract from “Analysis of starlight”, by John B. Hearnshaw

All in all, one is left with the impression that the scientific establishment is seriously allergic to the notion that all stars are binaries. Moreover, it would appear that practically anything goes when it comes to rescuing the heliocentric model from its many fallacies and aberrations. This is hardly a constructive attitude towards the advancement of human knowledge, nor is it a good example of the dialectic required by objective scientific discourse.

26.5 The great Hubble misconception

Incredibly enough, ‘Big Bang’ theorists have somehow seized upon Edwin Hubble’s work to back up their models of a constantly expanding universe. This, in spite of the fact that Hubble himself eventually stated that his findings did not suggest that our universe is continuously expanding, i.e. the higher redshift detected in ever more distant galaxies does not equate to accelerating rates of recession (the supposed drifting away of galaxies from our solar system). In any event, the expanding universe theory has been refuted in later decades by scores of eminent researchers and is a long shot from being universally accepted.

“In December 1941, Hubble reported to the American Association for the Advancement of Science that results from a six-year survey with the Mt. Wilson telescope did not support the expanding universe theory.” “Edwin Hubble” - Wikipedia

In his paper titled “Misconceptions about the Hubble recession law” (2009), Wilfred H. Sorrell made these important points:

“Almost all astronomers now believe that the Hubble recession law was directly inferred from astronomical observations. It turns out that this common belief is completely false. Those models advocating the idea of an expanding universe are ill-founded on observational grounds. This means that the Hubble recession law is really a working hypothesis. One approach is to use a simple deductive argument with only one basic premise. This premise states that the universe is static and stable. Here static means that the whole universe is undergoing no large-scale expansion or contraction. The past eight decades of astronomical observations do not necessarily support the idea of an expanding universe. This statement is the final answer to the question asked in Sect. 1 of the present study. Reber (1982) made the interesting point that Edwin Hubble was not a promoter of the expanding universe idea. Some personal communications from Hubble reveal that he thought a model universe based upon the tired-light hypothesis is more simple and less irrational than a model universe based upon an expanding space-time geometry.” “Misconceptions about the Hubble recession law” by W. H. Sorrell (2009)

It is therefore most ironic that the ‘Big Bang’ proponents are, still today, referring to Hubble’s lifelong work as supportive of their hypothesis of an explosive coming into being of the universe out of nothing. Fear not, though: the TYCHOS model does not pretend to propose an alternative to the awkward ‘Big Bang’ narrative, but merely to correctly interpret the empirical observations painstakingly gathered over the centuries by competent and level-headed astronomers in their quest to understand our cosmic environment.

Having said that, the TYCHOS model does offer a rational explanation as to why the components of distant galaxies appear to violate Newton’s gravitational ‘laws’ by revolving far too fast around their nuclei. In Chapter 21, we saw that, according to the TYCHOS model, the stars are 42633 times closer to Earth than currently believed by the mainstream astronomy establishment. If they are in fact at the distance estimated with the aid of the TYCHOS framework, there would be nothing exorbitant about their orbital velocities. Consequently, none of that elusive ‘dark matter’ currently thought to make up most of our universe and to be responsible for inordinate orbital speeds would need to exist.

26.6 The ‘double nucleus’ of the Andromeda galaxy

You will most likely have heard of Andromeda, the Milky Way’s closest ‘galactic’ neighbor, said to be some 2.5 million light years away (that’s 24 000 000 000 000 000 000 km)! It is easily visible to the naked eye on dark nights and we are told that it is expected to collide directly with the Milky Way in about 4 billion years as it is supposedly approaching us at the formidable speed of 301 km/s (that’s over 1 million km/h)! Now, one must wonder how these predictions can be harmonized with the idea of an ever-expanding universe, but the National Radio Astronomy Observatory assures us:

“The Andromeda and Milky Way galaxies are moving toward each other due to mutual gravitational attraction. This mutual gravity force is stronger than the force which causes the expansion of the Universe on the relatively short distances between Andromeda and the Milky Way.” “Why are the Milky Way and Andromeda Galaxies Moving Toward Each Other While the Universe is Expanding?”

In other words, they are actually telling us that, yes, the universe as a whole is expanding, yet if two ‘galaxies’ are close enough to each other, their ‘mutual gravitational attraction’ will prevail over the primal forces (supposedly released by the ‘Big Bang’) that govern the universe. Good Lord, does any of this make sense?

Let us leave it at that and instead take a look at a far more interesting aspect of the Andromeda system, also named ‘M31’. As few people will know, back in 1991 M31 was discovered to possess a distinct double structure: a larger and brighter component, and a far smaller and dimmer component. Still more interestingly, on the official ESA website we may read that “the true center of the galaxy is really the dimmer component”. Incidentally, in the TYCHOS the larger and brighter component (the Sun) is also not the center of the system.

Fig. 26.11 Original caption: “The center of M31 is twice as unusual as previously thought. In 1991 the Planetary Camera then onboard the Hubble Space Telescope pointed toward the center of our Milky Way’s closest major galactic neighbor: Andromeda (M31). To everyone’s surprise, M31’s nucleus showed a double structure.”

Fig. 26.11 Original caption: “The center of M31 is twice as unusual as previously thought. In 1991 the Planetary Camera then onboard the Hubble Space Telescope pointed toward the center of our Milky Way’s closest major galactic neighbor: Andromeda (M31). To everyone’s surprise, M31’s nucleus showed a double structure.”

When viewed through the lens of the TYCHOS model, this little-known 1991 discovery credited to Tod R. Lauer of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory becomes quite interesting: if even ‘galaxies’ are observed to exhibit double structures (the smaller component of which is located at the center), we have a clear parallel to the binary structure of our own system, in which the smaller component (Earth) orbits near the barycenter. Now, even if we apply the TYCHOS reduction factor (see Chapter 23), Andromeda would still be a hefty (though far more reasonable) 3 763 000 AU away from us (i.e., about 3.7 million times farther away than our Sun).

Binary or multiple systems appear to be the rule in the universe. A paper published recently (June 2022) in the Astrophysical Journal looks at the various discoveries of binary systems within the Andromeda system itself:

“In this paper, we report the discovery of two massive binaries with twin components (identified as massive twin binaries) in M31. These two twin binaries were reported in the catalog of Vilardell et al. (2006). (…) A large number of EBs (eclipsing binaries) have been discovered in M31 by ground-based surveys, e.g., DIRECT (Kaluzny et al. 1998, 1999; Stanek et al. 1998, 1999; Mochejska et al. 1999; Bonanos et al. 2003), Pan-STARRS 1 (PS1; Lee et al. 2014), and other photometric observations (Todd et al. 2005; Vilardell et al. 2006). So now we have the opportunity to test stellar evolutionary models by analyzing the evolutionary stages of these EBs (eclipsing binaries) in M31.” The Astrophysical Journal(2022)

Incidentally, the fact that Andromeda is currently observed to approach our solar system would make sense in the TYCHOS model since Earth is currently moving towards 00h42min of RA, which is almost straight in the direction of Andromeda. If we apply the TYCHOS reduction factor to the officially estimated approach velocity, we obtain 25.4 km/h (1 083 600 km/h / 42633), or what we might call a ‘bicycle speed’. This relatively tranquil displacement does not necessarily imply that the two systems are on a cataclysmic collision course, but could be due to some cyclical dynamic involving our system and Andromeda.

In conclusion, it may reasonably be posited that:

‒ Andromeda may just be a particularly large binary system.

‒ Its larger component revolves around its smaller component, much like the Sun revolves around the Earth.

‒ The ‘bicycle speed’ (25.4 km/h) at which it approaches our solar system does not mean the two systems will eventually collide.

26.7 Esclangon’s ‘dissymmetry of space’

I never cease to marvel at the amazingly precise observations made by some of the best astronomers of yesteryear. Their relentless commitment to the noble quest of unveiling the secrets of our cosmos has not been in vain, even if it has sometimes remained hidden from the public eye. I am glad to have been able to help renew interest in their fine contributions. Professor Ernest Esclangon is one such ‘unsung hero’.

Fig. 26.12 Ernest Esclangon

Fig. 26.12 Ernest Esclangon

Ernest Esclangon (1876-1954) was the director of the Strasbourg Observatory and the Paris Observatory before becoming the president of the Société Astronomique de France. In France, he is acknowledged as one of the most rigorous and exacting astronomers of his time. In his Wikipedia entry we can read that “Esclangon was attached to the establishment of the Chart of the Sky; it improved the precision of measurements in the fields of astronomy: measurement of time, variation of longitudes, variation of gravity”.

In short, Esclangon was certainly a major authority in astrometry, even though most people will never have heard of him. I came across his work while navigating a website dedicated to Maurice Allais—the man who effectively disproved Einstein’s theory of relativity. The following extract from the website of the Maurice Allais Foundation describes Esclangon’s most peculiar observational program carried out in 1927-28:

The observations of Ernest Esclangon

Between 25th February 1927 and 9th January 1928 Ernest Esclangon carried out, at the Strasbourg Observatory, a programme of optical observations following a very different procedure from that which had been almost exclusively used until then in interferometric observations. It was as follows:

a) A refracting telescope placed in the horizontal plane facing north-west, autocollimation is used to cause a horizontal thread located at the focus of the telescope to coincide with its image reflected on a mirror that is integrated with the telescope. The angular displacement required for this coincidence is denoted by c.

b) Turning the device to face north-east, the operation is repeated. The angular displacement required to obtain the coincidence this time is denoted by c’. The magnitude whose evolution has been monitored over time is (c-c’).

These observations comprised 40 000 sightings carried out by day as well as by night and divided into 150 series. The published reports included, in addition to a detailed description of the equipment used, the values for (c-c’) for each series and the average temperature during each series as well as temperature evolution over each series.

By adopting the standpoint of sidereal time, Ernest Esclangon had detected a sidereal diurnal periodic component, whereas nothing in particular emerged when solar time was adopted.

He published his findings in a communication to the Académie des Sciences: “Sur la dissymétrie optique de l’espace et les lois de la réflexion” (On the optical dissymmetry of space and the laws of reflection - December 27, 1927) in the April 1928 issue of the “Journal des Observateurs”, in which he also provided the experimental data collected: “Sur l’existence d’une dissymétrie optique de l’espace” (On the existence of dissymmetry of space). In making use of these data, Maurice Allais established the presence, in addition to the sidereal diurnal component, of at least one long periodic component (estimated on the basis of a rapid analysis to be half-yearly). “The re-examination of Miller’s interferometric observations and of Esclangon’s observations” - Fondation Maurice Allais

To the layman, this may sound like a dreadfully complex affair and it certainly took me a while to wrap my head around what exactly Esclangon’s observational program was all about. What could ‘an optical dissymmetry of space’ possibly signify? Well, allow me to illustrate the physical cause of this ‘dissymmetry’ observed by Esclangon. Believe it or not, it is yet another confirmation of the main pillar of the TYCHOS model, namely the Earth’s orbital speed of 1.6 km/h around its PVP orbit. Figure 26.13 reproduces the conclusion of Esclangon’s paper describing his observational program of Earth’s daily motions:

Fig. 26.13 Extract from: “ESCLANGON - Séance du 27 décembre 1927”

Fig. 26.13 Extract from: “ESCLANGON - Séance du 27 décembre 1927”

In short, Esclangon’s extensive telescopic observations from Strasbourg established that:

‒ Between 3 am and 3 pm (a 12-hour interval), the star quadrants at either side of Earth (looking north and south) appear to be ‘offset’ by -0.036″ and +0.036″, totaling 0.072″.

‒ Between 9 am and 9 pm (a 12-hour interval), the star quadrants at either side of Earth (looking east and west) display no dissymmetry in relation to the meridian.

These were Esclangon’s concluding thoughts:

“What is the origin of this dissymmetry? Does it come from the absolute movement of our star system? Categorical explanations would be premature. The question for now belongs to the experimental domain.”

Before proceeding, keep in mind the following key parameters stipulated by the TYCHOS model:

‒ Earth moves at 1.6 km/h in its PVP orbit, covering 38.428 km per day and 14036 km per year.

‒ This yearly motion of Earth causes stars located perpendicularly to Earth’s motion to appear to ‘precess’ by 51.136 arcseconds annually.

‒ In 12 hours, Earth will move by approximately 19.2 km (1.6 x 12). This amounts to 0.1368% of 14036 km.

Thus, the distance covered by Earth in 12 hours (19.2 km) represents 0.1368% of the distance covered by Earth in one year (14036 km). Now, Esclangon’s observed ‘dissymmetry’ amounted to 0.072″, although he slightly reduced this value to 0.070″ in a subsequent paper from 1928 .

And, lo and behold, 0.070″ amounts to ~0.1368% of 51.136″, the precession value of the TYCHOS model! It may therefore be concluded that the minuscule ‘dissymmetry’ detected by Esclangon was caused by the Earth’s 19.2-km displacement between 3 am and 3 pm. In fact, what he witnessed, to his great puzzlement, is fully consistent with Figure 26.5 featuring ‘Joe and Jim’(see top of this chapter).

Figures 26.14 and 26.15 should help illustrate the point: if we assume stars “X” and “Y” to be Esclangon’s referential points on either side of Earth, he would have expected both of them to be displaced towards the right of his meridian (or ‘line of sight’) following each of his 12-hour measurements. This, because he believed that the Earth revolves around the Sun.

Fig. 26.14 and 26.15

Fig. 26.14 and 26.15

Instead, to his great surprise, Esclangon saw his control stars “X” and “Y” moving in opposed directions in relation to his meridian. He therefore concluded that there must be some “dissymmetry of space” at play. Needless to say, Esclangon could not have realized the crucial significance of his observations or identified their underlying cause. But, if it is any consolation so belatedly, his expert observations may now be given the merit they deserve.

As a final note, the optical illusion of dissymmetry described by Esclangon is most probably what led Kepler to propose his bizarre theory of elliptical orbits. This is supported by a fascinating paper by Laurence Hecht titled “Optical Theory in the 19th Century - and the Truth about Michelson-Morley-Miller”. The entire paper is well worth the read, but the following statement stands out:

“The difference between the major and minor axis of the ellipse, which, as every school child is taught, constitutes the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, is about one part in one thousand.” Optical Theory in the 19th Century

One part in one thousand? Well, in the TYCHOS model the Earth moves across space at about 1.6 km/h and rotates at 1670 km/h at the equator. In other words, its orbital velocity is approximately 1/1000 of its rotational velocity. Similarly, the Earth’s daily motion along the PVP orbit amounts to approximately 1/1000 of its equatorial circumference. Let us perform the calculation with the most precise figures at our disposal:

Rotational speed of the Earth at the equator = 1670 km/h

Orbital speed of the Earth along the PVP orbit = 1.601169 km/h

Equatorial circumference of Earth = 40075 km

1670 km/h / 1.601169 km/h = 1042.98

40075 km / 38.428 km = 1042.86

In other words, the “one part in one thousand” mentioned by Hecht is commensurate with the ~1/1043 ratio observed between the rotational speed and orbital speed of the Earth, and between its equatorial circumference and its daily motion. It begins to make sense why Kepler erroneously concluded that Earth’s hypothesized orbit around the Sun would have to be slightly elliptical rather than uniformly circular. In fact, the Wikipedia entry for Johannes Kepler clearly states that he never explained how elliptical orbits could be derived from observational data and that the concept was really extrapolated from his work on Mars. Later on, in his “Epitome of Copernican Astronomy”, he arbitrarily applied the assumption to all the other planets.

“Finding that an elliptical orbit fit the Mars data, Kepler immediately concluded that all planets move in ellipses, with the Sun at one focus—his first law of planetary motion. Because he employed no calculating assistants, he did not extend the mathematical analysis beyond Mars. The Epitome contained all three laws of planetary motion and attempted to explain heavenly motions through physical causes. Although it explicitly extended the first two laws of planetary motion (applied to Mars in Astronomia nova) to all the planets as well as the Moon and the Medicean satellites of Jupiter, it did not explain how elliptical orbits could be derived from observational data.” “Johannes Kepler” - Wikipedia

For those with advanced knowledge of Kepler’s and Newton’s theorems, I would warmly recommend a paper by Gopi Krishna Vijaya, the conclusions of which are summarized below:

“Newtonian celestial mechanics is dependent on a proper understanding of Kepler’s Third Law, and its application, the wording of the law has been studied in its entirety in this paper. It has been shown that the form of Kepler’s Harmonic Law that is used in the literature, with reference to the semi-major axis alone, is primarily Newtonian – and ignores the constraint introduced by Kepler that the Law works in the way he had presented it only for small eccentricities. The implicit application of the Newtonian version of Kepler’s Harmonic Law in order to make it suitable for rectilinear ascents and descents is shown to be fundamentally flawed.” “Original form of Kepler’s Third Law and its misapplication in Propositions XXXII-XXXVII in Newton’s Principia” by Gopi Krishna Vijaya (2019)

In any event, it is safe to say that Kepler’s and Newton’s theories, despite their near-universal acceptance, have been shown to be mutually contradictory. They cannot therefore be invoked as evidence against the tenets of the TYCHOS model or in support of heliocentrism. In the next chapter, we shall take a look at what may be the gravest and most ‘momentous’ incongruity of Newtonian physics, namely the ‘missing’ (or ‘near-zero’) angular momentum of the Sun implied by the heliocentric paradigm.