Preface

The TYCHOS model is the result of almost a decade of steady research into ancient and modern astronomical literature, data and teachings. It all started as a personal quest to probe a number of issues and incongruities that, in my mind, afflicted Copernicus’ famed (and almost universally accepted) heliocentric theory. The TYCHOS model is based on, inspired by—and built around—both modern and time-honoured astronomical data.

As I gradually came to realize that the Copernican/Keplerian model presented some truly insurmountable problems as to its proposed physics and geometry, I decided to put to the test, in methodical fashion, what was once its most formidable adversary, namely the geo-heliocentric Tychonic model devised by Tycho Brahe—arguably the greatest observational astronomer of all times. After his untimely death in 1601 (at age 55), Tycho Brahe’s favourite assistant Christen Longomontanus perfected his master’s lifetime work in his Astronomia Danica (1622), a monumental treatise regarded as Tycho Brahe’s testament. The most striking feature of Tycho Brahe’s Solar System was that the orbits of the Sun and Mars intersect—as they both ‘dance’ around the Earth. Tycho Brahe, however, apparently believed for most of his life that the Earth was completely immobile, not even rotating around its own axis. This unlikely notion was amended by Longomontanus in his Astronomia Danica by giving Earth a diurnal rotation. This is known today as the “Semi-Tychonic model”, and my TYCHOS model is, in fact, nothing but a revised and ‘upgraded’ version of the same (the two are geometrically identical).

Most notably, the TYCHOS propounds and demonstrates that our rotating planet isn’t stationary in space but that it has, in all logic, an orbit of its own, just like all the celestial bodies that we can observe in our skies. In short, the essential soundness of Tycho’s (or rather, Longomontanus’) original model led me to envision the missing pieces of their rigorous yet incomplete work. If Tycho Brahe and his trusty assistant had been aware of what modern astronomers have learned in later decades, there is no doubt in my mind that they would have reached similar conclusions to those presented in this book.

In the latest decades of astronomical research, a particular realization stands out for its paradigm-changing nature: the vast majority of our visible stars have turned out to have a smaller, binary companion. Thanks to modern, advanced telescopes and spectrographic technologies, such binary pairs—formerly believed to be single stars—are now being discovered virtually every day, with no end in sight. In fact, since the so-called companion stars are often too small and dim to be detected, it is quite plausible that 100% of the stars in our skies are binary systems. In binary systems, a large star and a smaller celestial body revolve in relatively short, mutually intersecting local orbits around a common barycentre.

The TYCHOS posits that the Sun and Mars constitute a binary system, much like the vast majority (or perhaps all) of our surrounding stars. In our system, the Earth is located at or near the barycentre of the revolving Sun-Mars binary duo; it orbits ‘clockwise’ at the tranquil ‘snail-pace’ of 1 mph (or 1.6 km/h), completing one orbit in 25344 years—a period commonly known as ‘the precession of the equinoxes’. It is noted for pertinent comparison that the Sirius binary system is composed of two bodies (Sirius A and Sirius B) whose observed, highly unequal diameters are, remarkably enough, proportionally identical to those of the Sun and Mars.

Aside from Tycho Brahe’s unequalled body of empirical observations, my work has relied and expanded upon a number of lesser-known, overlooked or neglected teachings that were effectively ‘obliterated’ by the so-called Copernican Revolution. The early insightful architects who laid the groundwork for what should be our correct model for the Solar System include Nilakantha Somayaji (author of the Tantrasangraha, 1501) and Samanta Candrasekhara Simha (a.k.a. Pathani Samanta, 1835-1904), in addition to ancient Mayan, Aztec, Sumerian, Greek, Arabic and Chinese astronomers. Alas, their work and findings have long been eclipsed by a celebrated clique of modern science icons (e.g., Kepler, Galileo, Newton, Einstein), all of whom have been shown—in one way or another—to have engaged in deception, plagiarism or quackery, if not outright fraud. Having said that, I do realize that my TYCHOS model is primarily based upon the work of an astronomer from the Western world, Tycho Brahe—yet nothing suggests that he ever engaged in anything else than earnest and rigorous observations of the planetary motions in our skies, for his entire lifetime.

Unfortunately, in spite of the unprecedented accuracy of Brahe’s lifelong observational enterprise, his proposed geometric configuration of our Solar System was ultimately flipped on its head by his young and ambitious assistant, Johannes Kepler: in what must be one of the most ruinous setbacks in the history of science, shortly after Tycho’s untimely death, Kepler went on to steal the bulk of his master’s laboriously compiled observational tables only to tweak and distort them through his tortuous algebraic efforts so as to make them appear compatible with the paradigm of the diametrically opposed, heliocentric Copernican model.

As few people will know, Kepler was ultimately exposed (in 1988) for having crudely manipulated Brahe’s all-important observational data of Mars; Brahe had specifically entrusted him with the task of resolving the baffling behaviour of this particular celestial body, and Kepler’s laws of planetary motion were, in fact, almost exclusively derived (‘mathemagically’, one might say) from his harrowing “war on Mars”, as he liked to call it in his correspondence with friends and colleagues. Just why Mars presented such exceptional difficulties should become self-evident in the following pages.

“Kepler’s Laws are wonderful as a description of the motions of the planets. However, they provide no explanation of why the planets move in this way.” “Kepler’s Laws and Newton’s Laws” - from a course at Mount Holyoke College, Massachusetts

It is a widespread popular myth that Johannes Kepler was the man who brought on the era of “rational scientific determinism” to the detriment of dogmatic religious belief. However, as pointed out by J. R. Voelkel in his 2001 treatise “The Composition of Kepler’s Astronomia Nova”, nothing is further from the truth:

“He (Kepler) sought to redirect his religious aspirations into astronomy by arguing that the heliocentric system of the world made plain the glory of God in His creation of the world. Thus he made the establishment of the physical truth of heliocentrism a religious vocation.” “The Composition of Kepler’s Astronomia Nova” – by J.R. Voelkel (2001)

Paradoxically, the so-called Copernican Revolution was hailed as “the triumph of the scientific method over religious dogma”. Yet, when challenged by the likes of Tycho Brahe about the absurd distances and titanic sizes of the stars that the Copernican model’s tenets implied, the proponents of the same invoked the ‘omnipotence of God’:

“Tycho Brahe, the most prominent and accomplished astronomer of his era, made measurements of the apparent sizes of the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets. From these he showed that within a geocentric cosmos these bodies were of comparable sizes, with the Sun being the largest body and the Moon the smallest. He further showed that within a heliocentric cosmos, the stars had to be absurdly large - with the smallest star dwarfing even the Sun. Various Copernicans responded to this issue of observation and geometry by appealing to the power of God: They argued that giant stars were not absurd because even such giant objects were nothing compared to an infinite God, and that in fact the Copernican stars pointed out the power of God to humankind. Tycho rejected this argument.” “Regarding how Tycho Brahe noted the Absurdity of the Copernican Theory regarding the Bigness of Stars, while the Copernicans appealed to God to answer that Absurdity” by Christopher M. Graney (2011)

Indeed, if you had been questioning the Copernican model back in its heyday, you might have been called “a person of the vulgar sort”, since, according to Copernicans, you were questioning God’s divine omnipotence!

“Rather than give up their theory in the face of seemingly incontrovertible physical evidence, Copernicans were forced to appeal to divine omnipotence. ‘These things that vulgar sorts see as absurd at first glance are not easily charged with absurdity, for in fact divine Sapience and Majesty are far greater than they understand,’ wrote Copernican Christoph Rothmann in a letter to Tycho Brahe. ‘Grant the vastness of the Universe and the sizes of the stars to be as great as you like - these will still bear no proportion to the infinite Creator. It reckons that the greater the king, so much greater and larger the palace befitting his majesty. So how great a palace do you reckon is fitting to GOD?’” “The Case Against Copernicus” by Dennis Danielson and Christopher M. Graney (2014)

It can hardly be denied that the Copernican model is marred by a number of problems and oddities which, objectively speaking, challenge the limits of our human senses and perceptions. In any event, there is nothing intuitive about the Copernican theory; it is safe to say that its widespread acceptance relies upon the authority accorded to the edicts of a few prominent luminaries who, about four centuries ago, established for all mankind the definitive configuration of our Solar System. Since then, a myriad of questions have been raised as to the validity of its foundational tenets—yet such criticism keeps being dismissed and condemned as nothing short of heretical by the scientific establishment. Indeed, the fundamental premises of the Copernican model have been subjected over the years to countless critiques and falsifications, all of which have been ‘patched up’ by assorted ad hoc adjustments.

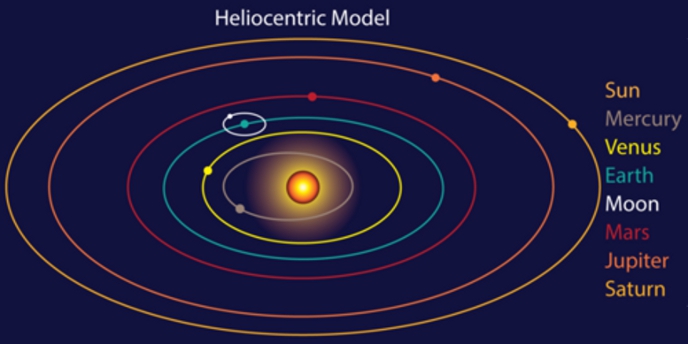

The Copernican/Keplerian “carousel”: pretty - but impossible

Let us now remind ourselves of the Copernican model’s simple geometric configuration, ‘starring’ the Sun as occupying the centre of a multi-lane ‘carousel’ of planets revolving around our star in concentric/elliptical orbits. Here it is, as presented to us since our school days:

The Copernican model undeniably appeals to our natural senses, what with its plain and orderly layout; there is a clear ‘middle’, and what’s more: there is an object occupying the middle, which happens to be the brightest object in our skies: the Sun. The problem is that its geometric layout gravely conflicts with empirical observation—unless you are willing to reject the core principles of Euclidean space. To wit, it simply doesn’t hold up to scrutiny as it implies impossible planet/star conjunctions and retrograde planetary periods. It cannot therefore possibly represent reality, as will be amply demonstrated in the following chapters. The Copernican model is outright non-physical since it violates the most elementary laws of geometry and perspective.

The current Copernican theory (which claims that the Sun needs some 240 million years to complete one orbit) clashes with the observable fact that the overwhelming majority of our visible stars appear to have small ‘local’ orbits of their own, with relatively short periods. For instance, Sirius A and B revolve around each other in about 50 (solar) years, the Alpha Centauri A and B binary pair do so in 79 years, while the Polaris A and B binary pair do the same in just 29.6 years. Other recently discovered binary systems exhibit even shorter ‘mutual orbital periods’ of only a few months, weeks, days, or hours. None of our visible stars are observed to have orbits in the range of hundreds of millions of years. Moreover, no star system has ever been observed to resemble the ‘Copernican carousel’ (as illustrated above), with a central, ‘fixed’ star surrounded by bodies revolving in neat, concentric circles.

I will venture to say that the TYCHOS model satisfies both sides of the age-old heliocentric vs. geo-heliocentric debate, since it proposes an ideal and ‘unifying’ solution that may appeal to both parties—if only they would agree to sit down for a rational discussion. In the TYCHOS, the Earth is neither static nor immobile; nor does it hurtle across space at hypersonic speeds. Nor is our planet located smack in the middle of the Universe “by the will of God”. Instead, it is simply located at (or near) the barycentre of our very own little binary system. All in all, the TYCHOS harmoniously combines elements from both of these competing cosmological models and even revives Plato’s ideal concept of uniform circular motion:

“In fact, for Plato, the most perfect motion would be uniform circular motion, motion in a circle at a constant rate of speed.” “The Geocentric View of Eudoxus” - Princeton University

Yes, this book is a quite unorthodox scientific publication, much unlike those conventional academic papers we are all accustomed to. I make no apologies for it and can only hope it will be appreciated for its earnest attempt to attract a larger audience to the wondrous realm of astronomy, interest in which, sadly, appears to have reached an all-time low amongst the general public (for a number of reasons which would deserve a separate study). To ease explanations, I have done my best to illustrate the TYCHOS model’s tenets visually, with the aid of colourful graphics and diagrams, much in the manner of a children’s school book; I have also striven to use the simplest possible maths at all times to make the text accessible to the widest possible readership—including myself: I have always found complex equations exceedingly tedious, abstract and inadequate to describe our surrounding reality. Fortunately, the core principles of the TYCHOS model can be expressed and outlined with a bare minimum of computations—all in the good tradition of Tycho Brahe’s philosophical outlook which the great astronomer succinctly summarized in this famous maxim:

“So Mathematical Truth prefers simple words since the language of Truth is itself simple.”

The TYCHOS model is built upon the mostly unchallenged raw data collected over the ages by this planet’s most dedicated and rigorous observational astronomers. Yet, it also integrates and highlights numerous recent studies and discoveries, many of which appear to have been ‘swept under the rug’ by our world’s scientific establishment. Its tenets have been developed around a holistic and methodical reinterpretation of ancient, medieval and modern astronomical knowledge, combined with a few ‘lucky strikes’ of my own. I will kindly ask all freethinking people of integrity to carefully assess its core principles with an open mind, devoid of any prejudice or preconceptions. If you can overcome the first and most obvious thought hurdle (i.e., “how could all our world’s astronomers possibly be wrong?”), I trust you’ll enjoy the journey across the richly illustrated pages of this book which, after all, presents a fully working geometric configuration of our Solar System while resolving a great many puzzles of modern astronomy.