Chapter 19: Understanding the TYCHOS Great Year

19.1 Why the stars keep drifting ‘eastwards’

Ever since antiquity, astronomers and astrologers have been aware of the so-called Precession of the Equinoxes―the fact that every 2100 years or so our firmament appears to drift eastwards in relation to Earth’s equinoxes by 30 degrees, roughly corresponding to one of the twelve ‘ages’ or constellations of the Zodiac. In our modern times, astrologers are often scoffed at for their allegedly unscientific and emotional approach to the cosmic realm. Ironically, astronomers have not been any more successful at producing a logical and scientific explanation for the Precession of the Equinoxes.

The graphic in Figure 19.1 shows how the TYCHOS model accounts for what is actually observed, as all the stars are seen to drift ‘eastwards’ by about 51” arcseconds every year. As Earth moves clockwise (i.e. ‘westards’) around its PVP orbit, it will drift by 30° every 2112 years, which will eventually add up to a full 360° circle in 25344 years (2112 X 12 = 25344).

Fig. 19.1 Earth’s clockwise motion around its PVP orbit causes our orientation vis-à-vis the stars to drift by 30° every 2112 years. A full 360° PVP revolution is completed in 25344 years (2112 × 12), corresponding to 1 ‘TYCHOS Great Year’ (TGY).

Fig. 19.1 Earth’s clockwise motion around its PVP orbit causes our orientation vis-à-vis the stars to drift by 30° every 2112 years. A full 360° PVP revolution is completed in 25344 years (2112 × 12), corresponding to 1 ‘TYCHOS Great Year’ (TGY).

Most attribute what is today called the General Precession to the so-called ‘lunisolar wobble’, a bizarre theory that has already been thoroughly refuted (see Chapter 10). Why astronomers refuse to acknowledge that heliocentrism lacks a plausible, rational explanation for the Earth’s all-important equinoctial precession is a mystery in itself (as well as a major yet unspoken embarrassment). In fact, it sometimes seems like ‘astro-nomers’ are no less prone to wishful thinking than their ‘astro-logical’ counterparts, despite being accused of trivializing the glorious cosmic milestones of human history, as suggested in this extract from Giorgio de Santillana’s fascinating 1969 essay, “Hamlet’s Mill”:

“For us, the Copernican system has stripped the Precession of its awesomeness, making it a purely earthly affair, the wobbles of an average planet’s individual course. But if, as it appeared once, it was the mysteriously ordained behavior of the heavenly sphere, or the cosmos as a whole, then who could escape astrological emotion? For the Precession took on an overpowering significance. It became the vast impenetrable pattern of fate itself, with one world-age succeeding another, as the invisible pointer of the equinox slid along the signs, each age bringing with it the rise and downfall of astral configurations and rulerships, with their earthly consequences”. “Hamlet’s Mill: An Essay on Myth and the Frame of Time” (1969)

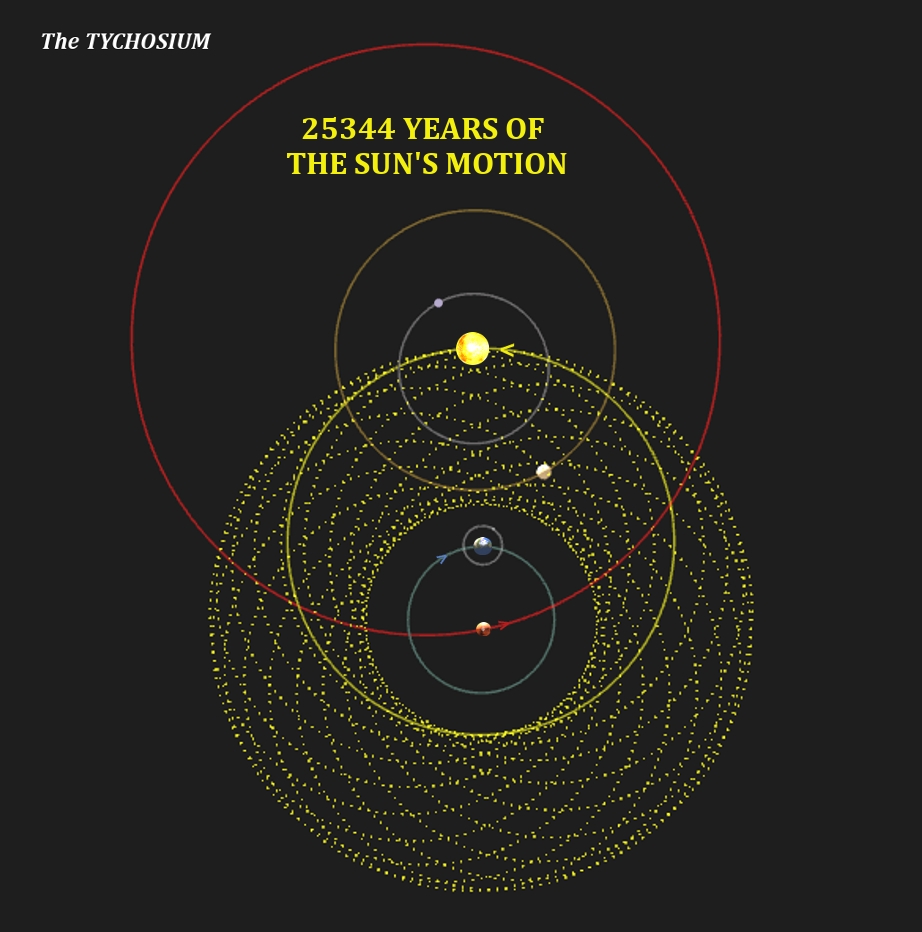

As shown in Chapter 11, the Precession of the Equinoxes can readily be explained and illustrated in the TYCHOS: it is simply the natural consequence of Earth’s slow, ‘clockwise’ revolution around its PVP orbit, which it completes in 25344 years. Figure 19.2 depicts the Sun’s trajectory over a full TGY (Tychos Great Year) of 25344 solar years, as the Earth slowly revolves in the opposite direction.

Fig. 19.2 The ‘Tychos Great Year’ (TGY).

Fig. 19.2 The ‘Tychos Great Year’ (TGY).

I computed and composed the graphic in Figure 19.2 several years ago, using pen & paper and basic image editing software. Back then I hadn’t met Patrik Holmqvist, the Swedish programmer who made it possible to translate my 2-D drawings into 3-D motion graphics by engineering the wonderful Tychosium 3D simulator. I was obviously thrilled when I saw the exact same spirographic pattern materializing in the Tychosium 3D simulator which I had pored over nights on end in the early stages of my TYCHOS research. Figure 19.3 is a screenshot from the Tychosium 3D simulator showing how the Sun will in fact trace a gorgeous spirographic mandala over a 25344-year period. Today anyone can visualize it at the touch of a button, by checking the ‘Sun’ box in the Tychosium’s ‘Trace’ menu, selecting ‘1 second equals 1000 years’–and then clicking the ‘step forward’ box 25 times:

Fig. 19.3 25344 years of the Sun’s motion demonstrated in the Tychosium 3D simulator.

Fig. 19.3 25344 years of the Sun’s motion demonstrated in the Tychosium 3D simulator.

19.2 About the Gregorian calendar’s solar year count of 365.2425 days

I shall now recount the story of an early blunder of mine which I thankfully realized and corrected in time for the printed release of this 2nd Edition of the TYCHOS book. To be sure, to admit one’s own errors should be a laudable act in all fields of scientific endeavour, so I will gladly eat some humble pie here and now—but not without noting that, as it turns out, the correction of my early mistake actually ‘scores another point’ for the TYCHOS model! All in all, my early slip highlights the difficulty of wrapping our heads around the opposed orbital motions of the Sun and the Earth, coupled with our ever-gyrating, trochoidal frame of reference (which will be illustrated in Chapter 21). As stated in the Wikipedia, the Gregorian calendar is based on a year count of 365.2425.days:

“The Gregorian calendar, as used for civil and scientific purposes, is an international standard. It is a solar calendar that is designed to maintain synchrony with the mean tropical year. It has a cycle of 400 years (146,097 days). Each cycle repeats the months, dates, and weekdays. The average year length is 365.2425 days per year, a close approximation to the mean tropical year of 365.2422 days.” “Tropical Year ”- Wiktionary

In the 1st Edition of this book released back in 2018, I speculated about the Gregorian solar year count being in error—by as many as 31.5 minutes per year. As of my calculations, this seemed to imply that the Sun would end up, in 25344 years, on the diametrically opposed side of the Earth (thus inverting our summers and winters vis-à-vis our civil calendar). Only in the summer of 2023 did I realize the fallacy of my reasoning. Mind you, my argument (which proposed an ‘optimal’ count of 365.22057 days for our solar year, i.e. 31.5 minutes less than the Gregorian count) rested on sound logic and geometry and would actually be correct if the Earth did not spin around its axis but only moved at 1.6 km/ around its PVP orbit.

In short, I had strangely failed to connect the dots with a previous finding of mine, namely that of the annual 31.44-minute oscillation of the Sun in relation to our clocks (which will also be illustrated further on, in Chapter 21). In fact, probably the major—and perhaps insurmountable—difficulty of this book has been how to arrange its contents sequentially, for how can one possibly submit to the reader the “x, y, z” points of an elaborate thesis before having outlined its “a, b, c” premises? The only remedy to this dilemma, I suppose, is to read this book more than once!

Fortunately, as Patrik Holmqvist and I started building the Tychosium 3D simulator back in 2017, we judiciously chose to adopt the Gregorian solar year of 365.2425 days as the ‘constant time unit’ around which to construct the simulator—although we had briefly considered using my shorter year count. In hindsight, it was undoubtedly the right decision. For now, make a mental note of that peculiar “31.44-minute” figure which, as we shall soon see, plays a crucial role in validating the tenets of the TYCHOS model.

19.3 The apparent exponential increase of the equinoctial precession rate

The exact duration of the Copernican Great Year (or ‘Annus Magnus’) has never been determined with any degree of accuracy, as admitted by all earnest astronomers. This is because the observed precession appears to grow (at an ‘exponential rate of increase’) over the centuries, to the utter perplexity of the heliocentrists. Of course, tentative explanations abound, invoking the usual plethora of unfounded and untestable ‘gravitational perturbations’, ‘non-gravitational effects’, ‘secular turbulences’ and ‘chaotic states’.

Indeed, astronomers have vainly attempted to quantify and justify the rate of increase of the stars’ west-to-east precession rate only to find that it isn’t linear, but exponential. For instance, back in the 19th century, Simon Newcomb proposed a constant of 0.00022″ to predict the annual increase. Over time, however, this ‘constant of precession’ proved to be a misnomer since it wasn’t constant at all. In fact, the rate of increase has since then kept inflating, with a mean annual rate of 0.000337″ now being proposed for the past hundred years.

“The actual observed change between 1900, when the precession rate was 50.2564” p/y and the year 2000 when the rate was 50.290966” p/y (Astronomical Almanac) was 0.0337, equating to an annual rate of change of 0.000337” p/y over the last 100 years. (…) The constant seems to work for a while until a close examination of the precession observable shows it is increasing at an exponential rate, outstripping the fixed constant. Thus the equation, even with an annual addition falls a little farther behind each year.” “Response to The Precession Dialogues” by Walter Cruttenden at BRI blog (2009)

Could the TYCHOS model possibly provide a simple and rational explanation for the apparent exponential increase of the equinoctial precession rate, you may ask. On pains of being repetitive, the answer to that question is ‘yes’. Fig. 19.4 should clarify - once and for all - this longstanding enigma so vividly debated by astronomers throughout the centuries:

Fig. 19.4

Fig. 19.4

The difficulty of the matter lies in that the exponential increase of the equinoctial precession rate is the result of two separate, cumulative components:

-

The east-to-west lateral displacement of Earth in relation to the stars

-

The east-to-west secular rotation of Earth’s equinox in relation to the stars

The observed secular increase of the stellar precession is closely related to the apparent accelerations and decelerations of the motions of the Moon, Sun and Earth, and goes to resolve a string of long-standing and still hotly debated riddles of astronomy, including:

‒ The apparent secular decrease of the length of the tropical year

‒ The apparent acceleration of the Moon’s orbital speed

‒ The apparent secular increase of the length of the sidereal year

‒ The apparent deceleration of Earth’s rotational speed

Fig. 19.5 If Jim were aware of the Earth’s progression around its PVP orbit, all the apparent secular variations in the motions and rotations of the Moon, the Sun and the Earth would vanish.

Fig. 19.5 If Jim were aware of the Earth’s progression around its PVP orbit, all the apparent secular variations in the motions and rotations of the Moon, the Sun and the Earth would vanish.

As should be clear from Figure 19.5, all these apparent secular variations are part of the same effect of perspective. They are caused by the gradual angular shift of the Earth in relation to the Sun, the Moon and the background stars. Of course, under the heliocentric paradigm, no such angular shift would be expected since the Earth is believed to revolve around the Sun and to return to the ‘same place’ every solar year. For astronomers who choose to persist in the Copernican error, these apparent variations will forever remain a conundrum and a pretext for the concoction of extravagant hypotheses. Figure 19.5 illustrates what sort of erroneous conclusions Copernican astronomers may reach as they analyze the relative, secular motions of the Earth, the Sun and the Moon.

In the TYCHOS model, these perceived accelerations and decelerations of the Moon and Earth are illusory and only a matter of inverted geocentric/heliocentric spatial perspectives. The Moon’s revolution isn’t speeding up, nor is Earth’s rotation slowing down. All such assumptions made by Copernican astronomers are illusions that the TYCHOS can demonstrate to be—both qualitatively and quantitatively—a direct corollary of the Earth’s (hitherto unknown) motion along its PVP orbit.

In a 1932 astronomy paper, J. K. Fotheringham provided a precious piece of information that can help understand the impasse of the heliocentrists:

“It should be noted however, that when it was discovered that precession was subject to acceleration, the acceleration of precession was not usually included in the acceleration of the Moon’s motion, so that acceleration is generally expressed as if it were a term in the sidereal longitude, not in the longitude as measured from the equinox.” “The Determination of the Accelerations and Fluctuations in the Motions of the Sun and Moon” by J.K. Fotheringham (1932)

In other words, the Copernican astronomers who vividly discussed the Moon’s puzzling, apparent secular acceleration were measuring the Moon’s motion against the starry background and not in relation to Earth’s equinoctial points! Thus, they never envisioned the possibility of an illusory acceleration caused by the clockwise motion of the Earth-Moon system, slowly curving in space against the starry background. Nor did they, of course, ever entertain the prospect of the Sun revolving on an external orbit around Earth.

19.4 The Great Year of Mars

As we saw in Chapter 10, Copernican theorists attribute our Great Year (the period required for a complete Precession of the Equinoxes) to a clockwise wobble of the Earth’s polar axis—the infamous and roundly disproved lunisolar wobble theory. One might ask: if the wobble theory were correct, why would Mars exhibit a ‘Great Year’ of its own almost precisely twice as long as ours? What sort of ‘cosmic harmony’ could cause the orbital precession rate of Mars and the axial precession rate of the Earth to be locked in a 2:1 ratio? To be sure, Mars is indeed officially reckoned to have a 51000-year equinoctial cycle:

“The Martian equinoxes also precess, returning to an initial position over a period of about 51,000 years.” “A Change in the Weather” by Michael Allaby and Richard Garratt (2004)

Now, the fact that the Martian equinoxes precess in about 51000 years, equivalent to two of our ‘Great Years’, would be entirely expected under the TYCHOS paradigm since our two binary companions, the Sun and Mars, are locked in a 2:1 orbital ratio. Mars will thus naturally employ twice as much time to complete its own equinoctial precession.

“As a combined effect of the precession of the spin axis and the advance of the perihelion, alternate poles of Mars tilt towards the Sun at perihelion every 25,500 years – that is, on a 51,000-year cycle.” “The Planet Mars: A History of Observation & Discovery” by William Sheehan (1996)

In the TYCHOS model, 1 TGY lasts 25344 years. However, since the Earth ‘subtracts’ one of the Sun’s counter-clockwise revolutions every time it completes one clockwise PVP revolution, the TGY may more adequately be defined as the ‘25345-year solar cycle’. The Martian Great Year would therefore be expected to last 50690 years (25345 × 2). And, in fact, the Tychosium 3D simulator has Mars transiting in practically the same place in our skies on 21 June 2000 and on 21 June 52690 (a 50690-year interval).

As you can see, the body of evidence in support of Mars having a binary relationship with the Sun is overwhelming. Remarkably enough, as can be verified in the Tychosium 3D simulator, even our Moon exhibits a regular 25345-year cycle and, just like Mars, returns to virtually the same place in our skies every 50690 years (2 × 25345)!

19.5 Why Mars appears to rotate around its axis a little slower than Earth

As of the best astronomical observations, Mars appears to rotate once around its axis only about 40 minutes slower than Earth. One may rightly wonder: why would the rotational periods of Earth and Mars be so similar? Could perhaps Mars’s rotation around its axis be, in actuality, synchronous with Earth’s axial rotation rate? Let’s see if we can find any indications in support of this interesting hypothesis.

• Circumference of Earth’s PVP orbit = 355 724 597 km

• Circumference of Mars’ orbit = 1 435 079 524 km

• Earth/Mars ‘orbital ratio’: 1 435 079 524 / 355 724 597 ≈ 4.03

In a two-year timespan, Earth will move along its PVP orbit by 28072 km (14036 km x 2 ), an ‘angular amount’ which will correspond to a 113130-km ‘slice’ (28072 x 4.03) of Mars’ orbit. Hence, any Copernican astronomers wishing to determine Mars’ exact rate of motion will fail to account for half of this ‘slice’ (i.e. 113130 km / 2 = 56565 km) as they assess to their best capacities its biyearly return point against the stars.

Since Mars completes one of its long ESIs around the celestial sphere in 707 days (or 16968 hours), its ‘perceived orbital speed’―relative to terrestrial time―will be about 84575.6 km/h (1 435 079 524 km / 16968 h ≈ 84575.6 km/h). We see that Mars would thus employ approximately 40 minutes to ‘make up’ for the aforementioned 56565 km:

56565 km / 84575.6 km/h = 0.6688 h, or about 40.13 min

In other words, Mars will only appear to an earthly observer to rotate around its axis slower than Earth because the earthling will be offset by that amount in relation to Mars’ celestial position. He will thus wrongly conclude that Mars rotates around its axis about 40 minutes slower than Earth.

Fig. 19.6

Fig. 19.6

The conceptual graphic in Figure 19.6 illustrates how an earthly Copernican observer (Joe) will be led to think that Mars rotates around its axis slightly slower than Earth. The green dot marking a given point on the Martian surface will be seen by Joe from another angle after about 2 years, but in reality Mars has returned to the exact same angular orientation in space it had two years earlier.

Curiously, Mars’ equatorial rotational speed would thus be 890 km/h, or 1.88 times slower than that of the Earth (1670 km/h), while its mean circumference is 1.88 times smaller than Earth’s. Also, as we saw in Chapter 5 (Fig. 5.1), Mars revolves around the Sun in 687 days, or 1.88 x 365.25 days.

Lastly, consider this: the tilt of Mars’ polar axis is reckoned to be 25.2°. This is 1.8° more than Earth’s current axial tilt of 23.4°. However, the inclination of Mars’ orbit in relation to our ecliptic is reckoned to be 1.8°. In other words, the ‘absolute spatial orientation’ of Mars’ polar axis may quite possibly be identical to that of Earth’s polar axis.

In conclusion, Mars would appear to rotate around its axis in the very same amount of time as Earth and to be tilted at the very same angle as Earth. The significance of this is unclear, but it is certainly not supportive of the heliocentrists’ understanding of Mars and Earth as two independent and largely unrelated bodies randomly revolving around the Sun.