Chapter 5: Mars, the “key” that Kepler never found

5.1 How Kepler subverted Tycho Brahe’s lifelong work

Johannes Kepler famously stated that:

“Mars is the key to understanding the solar system.”

Kepler was notoriously obsessed with Mars for five harrowing years and, in his correspondence with fellow scientists, referred to his relentless pursuit as “his personal war on Mars”. We now know that, presumably out of sheer exhaustion, Kepler eventually resorted to the shameless manipulation of Tycho Brahe’s data, later published in his Astronomia Nova (a book still regarded as “the Bible of the Copernican Revolution”). This shocking discovery by Prof. Donahue, the American translator of Kepler’s epochal treatise, was made in 1988. Now, if Kepler had to cheat to make his heliocentric model work, what does this tell us about the overall soundness and credibility of the Keplerian and Copernican theories?

It will remain a mystery why Kepler, Brahe’s ‘math assistant’, eventually dismissed his own master’s cosmic model in favor of the Copernican―and this in spite of having once plotted a working diagram of Mars’ geocentric motions titled De Motibus Stellae Martis. History books only tell us that upon Brahe’s untimely death at age 55, Kepler seized the bulk of his master’s painstakingly collected observations and annotations only to set about flipping the Tychonian model on its head. Professor Donahue’s detailed descriptions of how Kepler fudged his all-important Mars computations to make them appear to confirm the core tenets of his thesis make for a most compelling read:

This short article succinctly sums up Kepler’s falsification of his much-heralded master work, Astronomia Nova.

“Done in 1609, Kepler’s fakery is one of the earliest known examples of the use of false data by a giant of modern science. Donahue, a science historian, turned up the falsified data while translating Kepler’s master work, Astronomia Nova, or The New Astronomy, into English.” “Pioneer Astronomer Faked Orbit Theory, Scholar Says” - by New York Times (January 23, 1990)

As I see it, Kepler’s manipulative antics are destined to go down in history as the triumph of mathematical abstraction over empirical observation. In his urge to make the befuddling behaviour of Mars agree with the heliocentric Copernican theory, he not only misused and twisted but outright subverted Brahe’s most precious and exacting observational data. In any event, there can be no doubt that Brahe’s priority and main concern was that of understanding the motions of Mars. The fact that he entrusted this crucial task to a young, ambitious and petulant assistant may well have been the greatest mistake of his life. Be that as it may, it is a documented fact that Brahe had identified an unexpected systematical inequality in the planetary motions which was “not known to Ptolemy or Copernicus”:

“Tycho also realized that Copernican predictions for all the planets differed systematically from the observations and wondered whether an additional inequality, not known to Ptolemy or Copernicus, might affect their motions. Or perhaps planetary theories should be referred to the true rather than mean Sun, as Ptolemy had done, and the other inequality could be solved by modifying the solar eccentricity. Given the similarity of Mars’s orbit to the Sun’s, Tycho suspected that the red planet might provide a key for reworking all the planetary theories.” “Longomontanus on Mars: The Last Ptolemaic Mathematical Astronomer Creates a Theory” by Richard Kremer

5.2 Mars’ two empiric sidereal intervals (ESI)

The ancient Mayan astronomers made careful observations of Mars’ motions and were clearly aware of the planet’s variable sidereal period, as viewed from Earth. As they kept count of the amount of days needed for Mars to realign with a given reference star, they saw that Mars had in fact two sidereal periods: a longer and more frequent period of about 707 days (the long ESI) and a shorter period of about 546 days (the short ESI).

It is the short ESI of approximately 546 days (nearly 1.5 solar years) that is of primary interest to us here. As will be comprehensively demonstrated in Chapter 7, the Copernican model can in no way account for this 546-day sidereal period.

“We discuss here a kind of period that we call the empiric sidereal interval (ESI), which we define as the number of days elapsed between consecutive passages of Mars through a given celestial longitude while in prograde motion. At first glance, one would imagine that the ESI would fluctuate widely about some mean because of the intervening retrograde loop, which in the case of Mars occupies 75 days on average between first stationary (cessation of) and second stationary (resumption of normal W-to-E motion). However, a closer look at modern astronomical ephemerides reveals that for a practical observer there are really two ESIs, a lengthier one that includes the retrograde loop (the long ESI) and a shorter one that does not (the short ESI).” “Ancient Maya documents concerning the movements of Mars” - (February 2001) by Harvey M. Bricker, Anthony F. Aveni and Victoria R. Bricker

The paper quoted above is a highly recommended read. It describes in great detail the Mayan astronomers’ extensive knowledge of Mars’ sidereal periods, although it ultimately fails to address the profound implications raised by the existence of two ESI’s for the same planet. So, you may ask, if Mars’ sidereal period is clearly either ~707 days (the long ESI) or ~546 days (the short ESI), why do most astronomers accept Kepler’s figure of 686.9 days? As we shall see, the binary configuration of our solar system and Mars’ peculiar, epitrochoidal orbital motion clearly explains how Mars can realign with a given star within a year and a half.

Here are the observable facts: Mars will realign with a given reference star seven times in a row at intervals of approximately 707 days, but the eighth time around Mars will realign with that same star in only about 546 days. In other words, over a span of approximately 15 years, Mars exhibits seven long ESIs and one short ESI.

Table 5.1

Table 5.1

Now, since 5495 divided by 8 is approximately 686.9 days, we can see how Kepler simply averaged these eight periods to produce his estimate of Mars’ sidereal period. As it is, Kepler’s 686.9-day interval is not something that can ever be observed from Earth. Thus, the currently accepted value for Mars’s ESI is a mere mathematical extrapolation based on the assumption that Earth revolves around the Sun once a year. Yet, as can be directly observed, Mars’ sidereal period does indeed exhibit the 15-year sequence shown above.

You may now justly ask, “How is this even possible? How can Mars realign with the same star, as seen from Earth, at two wholly different intervals?” This is indeed a very good question, one which Copernican astronomers have never been able to answer. In contrast, the TYCHOS model not only provides an answer, but obviates the question altogether: Mars must for demonstrable geometric reasons have two sidereal periods, as I will now further expound upon.

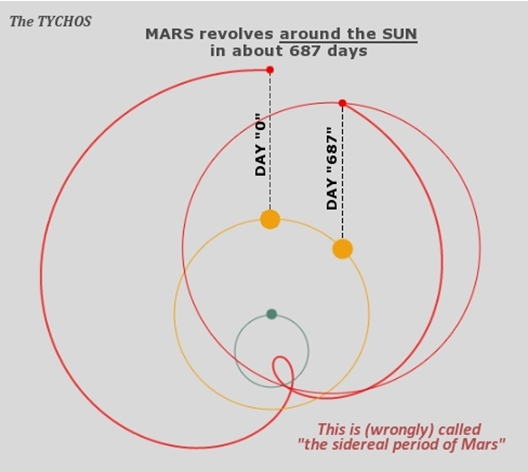

Please note that, in reality, Mars does indeed have a 686.9-day period (approximately 687 days), which is the time needed for Mars to revolve once around the Sun. This, however, is not Mars’ mean sidereal period, as viewed from Earth, but the period for Mars to return to its degree position relative to the Sun, as shown in Figure 5.1.

Fig. 5.1

Fig. 5.1

Why Mars is behaving in this way will become clear as we take a look at the synodic period of Mars.

5.2.1 The synodic period of Mars

We have just seen that Mars’ most frequent sidereal period (the long ESI) lasts on average 707 days (about 23 days less than two solar years of 730.5 days). Put differently, Mars returns facing the same star 23.3 days earlier than the Sun does, in a two-year period. The average synodic period of Mars is 779.2 days. This is the time needed for Mars to line up again with the Sun, as viewed from Earth. This is 48.7 days longer than two solar years (730.5 + 48.7 = 779.2). Thus, we have:

This leads us to a most remarkable realisation: since the two binary companions, Sun and Mars, are locked in a 2:1 orbital ratio, one might think they would ‘meet up’ every 730.5 days (2 solar years). But due to Mars retrograding biyearly by around 72 days on average, Mars will ‘slip out of phase’ with our timekeeper, the Sun―hence, with our earthly calendar. Therefore, as viewed from Earth, Sun and Mars will conjunct only every 779.2 days:

It follows that Mars completes 7.5 synodic periods in 16 solar years.

Every 16 years Mars and the Sun do in fact conjunct with Earth, although on opposite sides of our planet. Mars will need another 7.5 synodic cycles for a total of 32 years (i.e. 2 x 16, or 15 + 17) to complete one of its 32-year cycles. Since Mars processes biyearly (in relation to the Sun) by an average of ~45 min of Right Ascension, in 32 solar years it will process by about 1440 min RA:

Next, we will see how, as discovered by Tycho Brahe, the respective orbital paths of Sun and Mars can and do indeed intersect in typical binary fashion, much like the observed orbital behaviour of Sirius A and Sirius B―the brightest star system in our skies.

5.3 The binary dance of Sun and Mars

As mentioned earlier, Brahe’s boldest contention was undoubtedly that the orbits of Mars and the Sun intersect. Back then, his opponents would jeer: “Preposterous! Sooner or later, Mars and the Sun must collide!” Their pooh-poohing may perhaps be excused for back in Brahe’s day no one was aware of the existence of binary systems, the ubiquity of which was only established long after the invention of the telescope. In hindsight, one may graciously say that Brahe was ridiculed out of pre-telescopic academic ignorance.

The orbital configuration shown in Figure 5.2 is consistent with the models of Tycho Brahe and Pathani Samanta, with the exception of the ‘clockwise’ orbital motion of Earth―my main personal contribution to Brahe’s brilliant geoheliocentric model. For now though, let us focus our attention on Mars and its peculiar motion around the Sun and Earth.

Fig.5.2

Fig.5.2

The motions of Mars had the greatest astronomers of yore, including Brahe, scratching their heads:

“We have seen that Tycho, like Ptolemy and Copernicus, assumed the solar orbit to be simply an excentric circle with uniform motion. But already in 1591, he might have perceived from the motion of Mars that this could not be sufficient, as he wrote to the Landgrave that ‘it is evident that there is another inequality, arising from the solar excentricity, which insinuates itself into the apparent motion of the planets, and is more perceptible in the case of Mars, because his orbit is much smaller than those of Jupiter and Saturn.” p.346, “Tycho Brahe: a picture of scientific life and work in the sixteenth century” by John Louis Emil Dreyer (1890)

Mars has been the single most problematic body of observational astronomy for reasons that should become clear as we go along. The astronomy literature is sprinkled with comments hinting at the ‘uniqueness’ of Mars’ cosmic behaviour:

“Among the planets, Mars is a maverick, wandering off from the deferent-epicycle model more than most of the other planets.” “The Ballet of the Planets: A Mathematician’s Musings on the Elegance of Planetary Motion” by Donald Benson (2012)

Of course, all this head-scratching is unnecessary if one uses the correct configuration of the Solar System. Mars has been viewed as a ‘maverick’ for the simple reason that it is the binary companion of the Sun. In hindsight, one of Kepler’s most famous quotes rings like a most appropriate omen, the irony of which I trust future astronomy historians will underline:

“By the study of the orbit of Mars, we must either arrive at the secrets of astronomy or forever remain in ignorance of them.” — Johannes Kepler

Most remarkably, it so happens that, during his five-year-long “war on Mars”, Kepler evidently spent some serious time considering a geocentric configuration and even called Mars a “star”. His little-known diagram, De Motibus Stellae Martis (“Of the Motion of the Star Mars”), traced the motions of Mars between 1580 and 1596 (a 16-year period). It was obviously based on and computed from Brahe’s accurate observations, yet he ultimately discarded it. In Figure 5.3, we compare Kepler’s diagram with the same 16-year period as traced in the Tychosium 3D simulator. It looks like Kepler had at one time really been on to something!

Fig. 5.3 Mars in the TYCHOS model_________________________Fig. 5.4 Kepler’s little-known diagram.

Fig. 5.3 Mars in the TYCHOS model_________________________Fig. 5.4 Kepler’s little-known diagram.

Presumably, Kepler was simply unable to conceive how and why Mars―or any celestial body, for that matter―could possibly trace such oddly ‘looping’ trajectories. When it comes to envisioning the geometric dynamics of two magnetically bound, mutually orbiting objects (such as the Sun and Mars), the cognitive power of the human mind meets its limits. Modern motion graphics can help us overcome this mental hurdle and realise that these spirographic orbital patterns are merely the visual effect of an object revolving around another revolving object.

5.4 Is Mars a planet or a star?

Readers might wonder how a planet could possibly be the binary companion of our Sun, when binary systems like Sirius A and Sirius B are understood to be pairs of stars revolving around each other. But is Mars really a planet? Well, while Mars is identified as a planet in every modern school book, we have seen that Kepler for unknown reasons referred to Mars as a star. Although it is beyond the scope of this treatise to investigate how stars and planets are formed, I nonetheless wish to state my support for the hypothesis that planets are in reality very old stars which have cooled down and solidified into rocky spheres.

To be sure, this is not the position of mainstream astronomers who regard stars and planets as wholly different, mutually exclusive entities. On the other hand, in their voluminous study, Stellar Metamorphosis, Jeffrey Wolynski and Barrington Taylor make a compelling case that all the bodies in our cosmos are stars at different stages of evolution, and that planets and moons are quite simply very old, cooled-down stars:

“It is suggested that the rule of thumb of stellar age delineation is that old stars orbit younger ones, the younger ones being the more massive, hotter ones.” “Stellar Metamorphosis” by Jeffrey Wolynski & Barrington Taylor (2017)

Under this hypothesis, the “older star” of our binary Solar System would be Mars, as it orbits a “younger and hotter star” (the Sun). Interestingly, it has also been suggested that our Earth-Moon system may be a former binary star system which, as the two ‘shed their skin’, ended up as a planet and a satellite. To wit, the notion that Earth may be a former star shouldn’t sound too outlandish: after all, the fiery magma trapped in Earth’s core which occasionally spurts out of volcanoes may well be viewed as an indication that we are, in fact, living on the surface of an old, cooled-down star. In turn, our barren and volcano-less lunar satellite, the Moon, would according to the same hypothesis be an even older and cooler extinct star.

5.4.1 The 79-year cycle of Mars

“Long before Ptolemy, the Babylonians knew that the motion of Mars is repeated, very nearly, in a 79-year cycle – that is, oppositions of Mars occur at nearly the same longitude every 79 years.” The Ballet of the Planets: A Mathematician’s Musings on the Elegance of Planetary Motion by Donald Benson (2012)

The intervals between two Mars oppositions closest to (56.6 Mkm) or farthest from (101 Mkm) Earth will alternate between 15 and 17 years, due to the peculiar epitrochoidal path of Mars around the Sun and Earth. This produces a 15y / 17y / 15y / 15y / 17y pattern repeated every 79 years. Or you could think of it as five cycles of nearly 16 years: 79 / 16 = 4.9375

Mars’ unique, alternating 15/17-year pattern has never been satisfactorily explained until now. None of our other outer planets exhibits such an irregular pattern. Jupiter, for instance, invariably returns to the same place in our skies in about 12 solar years.

Here follows an extract from a Mars Opposition Catalogue, listing some past and future opposition dates of Mars (between September 1956 and September 2035) along with the respective Mars-Earth distances. As you can see, these distances vary from a minimum of ca. 56 Mkm to a maximum of ca. 101 Mkm. This full Mars opposition cycle resumes every 79 years — in the cyclic 15 y / 17 y / 15 y / 15 y / 17 y pattern mentioned earlier:

Table 5.2 Mars Oppositions from 1956 to 2035 - from “Mars Oppositions” - by Hartmut Frommert (2008)

In the Tychosium 3D simulator, Mars is shown to revolve around a uniformly circular orbit at constant speed. In fact, Kepler’s ‘laws’ of planetary motion, with their odd elliptical orbits and variable speeds, are simply a mathematical construct to make astronomical data compatible with the Copernican model. The same is true for Einstein’s temporally warping time-space, something we will come back to further on when we look at Mercury. It bears reminding that, before Kepler introduced these ‘laws’, astronomers all over the world had been relentlessly pursuing the ideal concept of uniform circular motion. In fact, so had Kepler himself, before he started stretching and squeezing the recalcitrant Martian motions observed by Brahe into ever more complex equations.

“The testimony of the ages confirms that the motions of the planets are orbicular. It is an immediate presumption of reason, reflected in experience, that their gyrations are perfect circles. For among figures it is circles, and among bodies the heavens, that are considered the most perfect. However, when experience is seen to teach something different to those who pay careful attention, namely, that the planets deviate from a simple circular path, it gives rise to a powerful sense of wonder, which at length drives men to look into causes.” (Extract from a short illustrated webpage: “Kepler’s Discovery” )

Please make a note of Mars’ peculiar 79-year cycle. We will soon look into the lesser-known 79-year cycle of the Sun and demonstrate an even closer, interrelated pattern between Mars and the Sun.

5.5 Mars’ opposition ring

With an average minimum distance from Earth of 56.6 Mkm and average maximum distance of 101 Mkm, the Mars oppositions allow to establish the diameter of the opposition ring: approximately 157.6 Mkm.

Fig. 5.5 Mars’ opposition ring.

Fig. 5.5 Mars’ opposition ring.

As it happens, this value (157.6 Mkm) reflects the difference between the orbital diameters of Mars and the Sun. Why is this significant? Consider the following:

→ Difference between orbital diameters of Mars and the Sun: 456.8 Mkm – 299.2 Mkm = 157.6 Mkm

→ Diameter of the “opposition ring” of Mars (around which all Mars oppositions occur) = 157.6 Mkm

→ When Mars finds itself in opposition (as it is observed to reverse direction in the sky for 72 days on average) it can transit as close to Earth as 56.6 Mkm or as far as 101 Mkm: 56.6 + 101 = 157.6 Mkm

5.6 Mars’ retrograde periods falsify the Copernican model

As Mars transits in so-called opposition (i.e. when Mars and the Sun find themselves on opposite sides of the Earth), its usual West-to-East motion will appear to reverse direction (or ‘retrograde’, as we say) and to proceed East to West against the starry background for a variable number of weeks. Figure 5.6 shows how the famed astro-photographer Tunc Tezel expertly captured the Mars retrogrades of 2003 and 2012, and how these two periods are traced in the TYCHOSIUM 3D simulator

Fig. 5.6

Fig. 5.6

Note that, in 2003, Mars passed almost twice closer to Earth (0.373AU - or 55.8 Mkm) than it did in 2012 (0.674AU - or 100.8 Mkm). Also, note that in 2003, Mars was observed to retrograde against the starry background by about 40min of RA (over 61 days) - whereas, in 2012, it retrograded by as many as 72min of RA (over 83 days) - as highlighted in my next diagram:

Fig. 5.7

Fig. 5.7

In other words, Mars reversed course for a shorter time and shorter distance in 2003 than in 2012. This is most remarkable because, according to the Copernican model, it should be precisely the other way around. As you may know, Copernicans contend that Mars appears to retrograde whenever Earth (in the ‘inside lane’) overtakes Mars (in the ‘outside lane’). The resulting change in perspective (or parallax) would then produce the optical illusion of Mars back-tracking in the sky against the starry background. If this were the case though, the closer Earth is to Mars during the ‘overtaking’, the larger the retrograde effect should be. Instead, the exact opposite is empirically observed.

Figures 5.8 and 5.9 provide a closer comparative view of the retrogrades of Mars in 2003 and 2012, as described above:

Fig. 5.8 and 5.9

Fig. 5.8 and 5.9

Mars’s observed retrograde motions are enough to falsify the entire Copernican theory beyond appeal. The heliocentric model’s explanation for the retrograde motions of our planets is inadmissible and must be discarded since it violates the most basic laws of spatial perspective. Allow me to further demonstrate this with a representation of a real-world optical situation anyone can easily relate to:

Fig. 5.10

Fig. 5.10

In Fig. 5.10, point ‘M’ (think Mars) will seem to retrograde by a larger amount to the driver of the red van than to the driver of the yellow van. However, Mars’ actual motion is quite simply the opposite of what we would see if the Copernican inner-lane/outer-lane hypothesis were correct.

In fact, there’s an even simpler way to experience and verify this for yourself without leaving your living room:

-

Raise your forefinger (think of it as being Mars) in front of your nose and stretch out your arm as far as you can.

-

Next, aim your outstretched arm at the books on the shelves (think of them as stars) at the far side of your living room.

-

Now rotate your neck from left to right as much as you can while keeping your eyes focused on your forefinger and the books on the shelves.

-

Observe how many books move from side to side in relation to your raised forefinger.

-

Now bring your forefinger 50% closer to your nose and repeat your left-to-right neck rotation.

-

Observe how a significantly larger portion of books will move from side to side in relation to your forefinger.

Fig. 5.11 When Mars was closest to Earth in 2003, it retrograded against the stars far less than it did in 2012.

Fig. 5.11 When Mars was closest to Earth in 2003, it retrograded against the stars far less than it did in 2012.

This basic law of perspective is as incontestable as it gets. Yet, incredibly enough, no Copernican astronomer has ever publicly admitted that the observed retrogrades of Mars roundly falsify their explanation of retrograde motions. As we shall see further on, the issue of Mars’ retrograde periods is not by any means the only aberration afflicting the Copernican model; there are a number of far graver―indeed insurmountable―problems with the heliocentric model children are taught in school.

By now it should be clear why Kepler decided to fudge with the highly accurate observational data provided by his master, Tycho Brahe. As the staunch Copernican he was, he missed the opportunity to make sense of the complex motions of Mars, what with its unequal retrograde periods and seemingly fluctuating orbital speeds. Kepler’s “war on Mars” was simply unwinnable, since the man was obstinately attached to the idea that the Sun had to be at the center of the system. I will thus dare say that his devious and obdurate ways will go down in history as a textbook case of how scientific investigations should not be pursued; Kepler’s ardent quest was fogged by that all-too-common defect of the human intellect: confirmation bias.

5.7 Is Mars’ orbital speed the same as the Sun’s?

The average orbital velocity of Mars is conventionally given as 86677 km/h, but this is without accounting for the distance covered by Mars during its retrograde loops, which heliocentrists believe can be dismissed as a mere optical illusion.

As shown in Table 5.1, the short ESI of Mars amounts to 546 days. However, this period is subject to fluctuations due to the eccentricity of Mars’ orbit, the lower bound being 546 days and the higher bound 565 days. If we average these two figures we get 555.5 days and ― lo and behold! ― the Tychosium 3D simulator shows that Mars can in fact complete one full revolution around the Earth in 555.5 days, or 13332 hours (Fig. 5.12). We thus have:

-

Official estimate of the circumference of Mars’ orbit: 1 429 085 052 km

-

Average time employed by Mars to complete a short ESI: 13332 hours

-

Orbital speed of Mars: 1 429 085 052 km / 13332 h = 107192 km/h

This is a whisker short of the Sun’s orbital speed (107226 km/h), but given the many variables involved, it may be reasonably assumed that the orbital velocities of the Sun and Mars are identical. Indeed, it would seem perfectly logical that binary companions in intersecting orbits would move around space at the same pace, notwithstanding their different orbital circumferences.

Fig. 5.12 The orbital speeds of the Sun and Mars may well be identical.

Fig. 5.12 The orbital speeds of the Sun and Mars may well be identical.

In the next chapter, we will take a good look at the astounding similarities between the Sirius binary system and our own system. Sirius, of course, is the brightest star in our skies. I trust the reader can imagine my pleasant surprise when in the early stages of my TYCHOS research I realised that the observed diameters of Sirius A and Sirius B are proportionally identical to those of the Sun and Mars.