Chapter 21: A Man’s Yearly Path, the Analemma - and the number 137

21.1 About trochoidal loops

In the TYCHOS model, the Earth proceeds at 1.6 km/h (~1 mph), covering an annual distance of ~14036 km (the EAM), a distance only 1280 km longer than Earth’s own diameter of 12756 km. The Earth makes a 360° rotation around its own axis every 23h56min (a sidereal day), but every 24 hours (a solar day) it will rotate by 361°. Hence, over the course of one month, a point on the surface of the Earth will be displaced by ~30° in relation to the firmament. Due to these combined rotational and translational motions, the path traced by a man standing still in one spot for a full year will be a trochoidal loop or, more precisely, a ‘prolate trochoid’ as shown in Figure 21.1.

Fig. 21.1

Fig. 21.1

A trochoid is simply a curve traced by a point fixed to a circle as it rolls along a straight line. Thus, an imaginary stationary astronomer in London (let’s call him Jim) patiently monitoring the annual motions of the star Vega through his telescope for a full year will be carried around a trochoidal path. This is illustrated in Figure 21.2.

Fig. 21.2

Fig. 21.2

Of course, unless Jim is aware of his own trochoidal motion (his ‘ever-looping frame of reference’), he will be baffled at star Vega’s seemingly inexplicable behavior in the course of a full year: as he records the successive positions of the star on a fixed photographic plate (which, of course, will gyrate in the same manner as himself), its annual motion will appear to trace a peculiar geometric curve known as a prolate trochoid:

Fig. 21.3 The trochoidal path of “Jim the astronomer”.

Fig. 21.3 The trochoidal path of “Jim the astronomer”.

Fig. 21.4 Modern diagram of the observed motions of the circumpolar star Vega over a 3-year period. Source: “Heliocentric parallax” by Michael Richmond (2014)

Fig. 21.4 Modern diagram of the observed motions of the circumpolar star Vega over a 3-year period. Source: “Heliocentric parallax” by Michael Richmond (2014)

Note that the shape and ‘height’ of these stellar trochoidal loops will vary depending on the celestial latitude of the star and on the observer’s earthly location. However, if the star is located along the Earth’s equatorial ecliptic, no trochoidal loop will be seen; instead, it will appear to proceed along a straight line while periodically reversing direction (retrograding) whenever Jim is temporarily ‘carried backwards’ in relation to the Earth’s forward motion, as shown in Figure 21.3.

Our Jim then decides to monitor another star, then another, and then another. He finally realizes that all the stars in our sky exhibit trochoidal motions and/or short retrograde periods. Jim, who just isn’t ready to abandon his long-nurtured convictions, may then come up with all sorts of ad hoc hypotheses to ‘explain the inexplicable’. This was, in fact, precisely the case with Astronomer Royal James Bradley who famously monitored the star Draconis for extended periods of time and, having later noticed that all the stars exhibit such looping paths, went on to formulate an abstruse theory that he named ‘Stellar Aberration’, or ‘The Aberration of Light’. But more about that in Chapter 22.

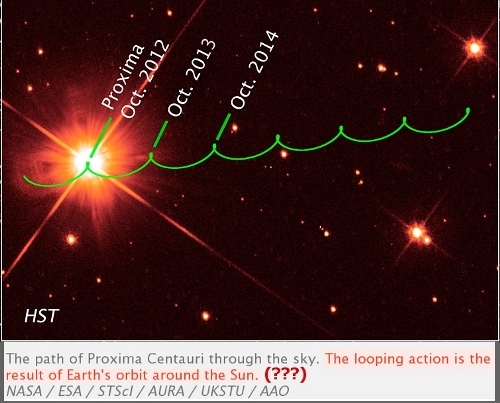

The image in Figure 21.5 is from a ‘mainstream’ astronomy website. It shows that even our nearmost star, Proxima Centauri, is seen to proceed along a trochoidal path similar to that of Vega, although the loops are ‘flatter’ due to Proxima’s lower celestial latitude (viewing angle):

FIg. 21.5 Image source: “Hunting for Planets Around Proxima Centauri” by David Dickinson (2016)

FIg. 21.5 Image source: “Hunting for Planets Around Proxima Centauri” by David Dickinson (2016)

Note the absurd, official explanation in Figure 21.5: “The looping action is the result of the Earth’s motion around the Sun”. Pray tell, how could this be the case? Surely, if our Solar System were moving at 800000 km/h (as officially claimed), thus covering some 7 billion kilometers annually, this looping pattern should be more elongated by several orders of magnitude; to wit, the spaces between the loops should be enormously larger and the loops themselves, which would only represent the 300 Mkm diameter of the Earth’s supposed orbit around the Sun, would hardly be noticeable: 300 Mkm is a mere 4.3% of 7 billion kilometers!

We shall now proceed to show how the annual trochoidal motion of an earthly observer can account for other still unexplained, or dubiously interpreted, celestial phenomena. Perhaps the most curious of them all is the observed annual motion of the Sun, as it traces an elongated ‘8’-shaped pattern in our skies. This geometric pattern traced by the Sun’s yearly motion is known as the ‘analemma’.

21.2 The analemma: a qualitative analysis

Any patient photographer can empirically verify the existence of the analemma by setting up a tripod and snapping pictures of the Sun at noon (say, every ten days or so) for a full year. What will be obtained is an elongated ‘8’-shaped curve (wider at the lower end) well-known to astronomers. In the past, the analemma used to be printed on the pretty globes adorning people’s living rooms. For some reason though, this is no longer the case.

Fig. 21.6 The analemma pictured on a world globe.

Fig. 21.6 The analemma pictured on a world globe.

Everyone has heard of the proverbial broken clock which will nonetheless show the correct time twice a day. However, not everyone knows that our earthly clocks are, strictly speaking, almost never on time. In fact, our clocks only agree with the Sun’s midday zenith 4 times a year. For the remaining part of the year, our clocks will be slipping in and out of sync with the Sun by as many as +16.5 minutes or -14 minutes, depending on the time of year.

But what exactly causes this curious analemma? Of course, the vertical component (December-June) of the analemma is due to the Sun’s shifting elevation between winter and summer associated with Earth’s axial tilt (23.4° x 2 = 46.8°), so no mystery there. On the other hand, the lateral component of the analemma (i.e. the alternating east/west drift of the Sun) has never been adequately explained. As current theory has it, it is caused by Earth’s elliptical orbit and its variable velocity around the same. This, we are told, would explain why the Sun’s zenith oscillates in our skies by more than half an hour. What sort of magical forces would cause Earth to speed up and slow down? And why would its orbit be elliptical? No such phenomena have ever been observed in nature. Yet, this has somehow been accepted as scientific fact, in the complete absence of experimental corroboration.

Fig. 21.7 The cause of the analemma’s vertical shift is readily explained. But what exactly causes its horizontal 3:1 asymmetry? No rational explanation for this has been submitted to this day.

Fig. 21.7 The cause of the analemma’s vertical shift is readily explained. But what exactly causes its horizontal 3:1 asymmetry? No rational explanation for this has been submitted to this day.

Note: Current theory about elliptical orbits and variable orbital velocities is roundly falsified by the observable fact that the Sun appears to ‘accelerate’ in June and July when the Sun-Earth distance reaches its maximum and a ‘deceleration’ would be expected. Direct observation is all that is needed to refute Kepler’s ‘laws’.

Indeed, the most curious aspect of the analemma is its conspicuously asymmetric 8-shape (thinner at the top and thicker at the bottom). Now, what could possibly cause this uneven distribution of the Sun’s annual east-west oscillation? Various theories have been advanced, yet none have definitively settled the question. In section 21.1, we saw that a man’s yearly path takes the form a prolate trochoid. Over a full year, this trochoidal motion has a lateral displacement ratio of 3:1 and, in fact, the asymmetry of the analemma exhibits a similar 3:1 ratio (readers may also recall the 3:1 ratio of the Moon’s trochoidal apsidal precession demonstrated in Chapter 13). The comparative diagram in Figure 21.8 should clarify the matter.

Fig. 21.8 How the TYCHOS model accounts for the analemma phenomenon.

Fig. 21.8 How the TYCHOS model accounts for the analemma phenomenon.

Note how the four occasions on which our earthly clocks ‘agree with the Sun’ (i.e. 16 June, 24 December, 29 August and 15 April) neatly coincide with the observed analemma. At this point, it should be intuitively evident to the reader that the analemma is, at least qualitatively speaking, closely related to what I like to call ‘a man’s yearly path’. Let’s now take a brief look at the math involved.

21.3 The analemma: a quantitative analysis

If in the course of a year our clocks can be ‘ahead’ by about 16.5 min and ‘behind’ by about 14 min, the total east-west offset of the Sun in relation to the true zenith would amount to 30.5 minutes. You may now ask: how then can we accurately measure time and calibrate our clocks (which, of course, tick at constant speed) with the solar motion if our celestial timekeeper (the Sun) keeps ‘accelerating’ and ‘decelerating’? Well, the thing is, we can’t.

The so-called Equation of Time is a clever man-made convention devised to deal as best as possible with this pesky lateral oscillation of the Sun. In fairness, the Equation of Time has provided an ingenious solution to the problem. Yet, the fact remains: our clocks, as useful as they are for our daily purposes, are cosmically speaking almost always ‘offset’ in relation to the Sun.

Note that the total observed annual ‘lateral drift’ of the Sun adds up to 30.5 min (16.5 min + 14 min) of RA. However, this is without accounting for the fact that an extra 3.93 min is added by convention, via the leap-year gimmick, every four years or so. To be precise, the long-term average is 3.76 min since some leap years are skipped. Therefore, 0.94 min (¼ of 3.76 min) should be added to the annual count of the Sun’s lateral drift:

30.5 min. + 0.94 min. = 31.44 min

In other words, the full annual east-west oscillation of the Sun around its ‘mean zenith’ amounts to 31.44 minutes. As you will recall, we already met this peculiar figure in Chapter 19 where I mentioned how one might ‘mathematically expect’ a TYCHOS solar year to last for 365.22057 days, i.e. circa 31.5 minutes less than the Gregorian solar year of 365.2425 days. However, such a calculation doesn’t take into account either the trochoidal path of the terrestrial observer (and time-keeper) nor the alternating Sun-Earth orbital directions and fluctuating Sun-Earth distances, nor the 23.4° tilt of our planet’s polar axis.

Now, to find the average rate of oscillation of the Sun over the four quadrants of our celestial sphere (i.e., the four seasons), we must divide our 31.44-minute figure by 4:

31.44min / 4 = 7.86min

Note that it matters not whether this mean figure of 7.86 min takes the minus sign or the plus sign, since the Sun’s motion can be either co-directional or counter-directional to Earth’s motion. We shall now verify whether this rate might be correlated with Earth’s orbital speed.

• Orbital speed of the Sun = 107226 km/h

• Orbital speed of the Earth = 1.601169 km/h

• 1.601169 km/h represents 0.00149326% of 107226 km/h

• Duration of 1 sidereal year = 525969.17 min

• 7.86 min represents 0.00149438% of 525969.17 min

Fig. 21.9

Fig. 21.9

Interestingly, the Sun (travelling at 107226 km/h) will employ just about 7.86 minutes to cover 14036 km, i.e. the annual distance covered by the Earth as it revolves along its PVP orbit.

In conclusion, the analemma could conceptually be envisioned as Earth’s ‘speedometer’ since its mean rate of east-west oscillation reflects our planet’s orbital speed of 1.6 km/h. In addition to this important realization, the following should be kept in mind:

- All astronomical observations must necessarily take into account the annual trochoidal motion of our earthly reference frame. This includes all matters pertaining to stellar motions and parallaxes—as well as when optimizing the solar year count for the purpose of perfecting our civil calendar’s synchrony with the Sun.

- This trochoidal motion is the main reason why we need the Equation of Time, along with the other factors and variables described above.

- The Sun’s annual 31.44-minute east-west oscillation goes to explain why the Gregorian calendar’s solar year count (365.2425 days) is about 31.5 minutes longer than that which might be expected in the TYCHOS model (365.22057 days), as discussed in the 1st Edition of this book.

Fig. 21.10 As Earth rotates and moves, a man will be carried around a trochoidal path. As he monitors the Sun’s position at noon over a full year, the Sun will appear to speed up and slow down (longitudinally) in relation to his clock. This is due to a combination of factors caused by (1) his own asymmetric spatial displacements, (2) the seasonally fluctuating relative Sun-Earth speeds, (3) the

Sun’s variable distance from Earth. The man’s clock will only ‘strike noon’ correctly 4 times a year—as the Sun traces in the sky the curious 8-shaped analemma.

Fig. 21.10 As Earth rotates and moves, a man will be carried around a trochoidal path. As he monitors the Sun’s position at noon over a full year, the Sun will appear to speed up and slow down (longitudinally) in relation to his clock. This is due to a combination of factors caused by (1) his own asymmetric spatial displacements, (2) the seasonally fluctuating relative Sun-Earth speeds, (3) the

Sun’s variable distance from Earth. The man’s clock will only ‘strike noon’ correctly 4 times a year—as the Sun traces in the sky the curious 8-shaped analemma.

21.4 The TYCHOS and the ‘magic’ 137 number

In Chapter 12 we saw that the solar year is shorter than the sidereal year. Our earthly estimates of the average daily distance covered by the Sun are of course based on the shorter solar year. However, a hypothetical observer on the Sun—let’s call him Prof. Sunstein—will gauge his own mean daily motion against the full celestial sphere of 1440 min of RA rather than the 1436.024 min of RA against which we gauge what we call ‘the solar year’ (a 0.2762% difference). In fact, here on Earth we see the Sun moving daily by 3.976 min of RA on average, which amounts to about 0.2762% of 1440 min. Since the Sun revolves around the Earth once a year, it will subtract one day (or a 0.2762% slice) from our earthly calculations. Prof. Sunstein is not subject to this illusion and so will correctly estimate the Sun to move by 0.2762% of its orbital circumference every day.

-

Circumference of the Sun’s orbit: 939 943 910 km

-

0.2762% of 939 943 910 km amounts to ~2 596 125 km

This 2 596 125 km value represents the ‘absolute’ daily distance covered by the Sun. Interestingly, it also turns out to be approximately 1/137 of the circumference of the PVP orbit:

-

Daily displacement of the Sun: 2 596 125 km

-

Circumference of the PVP orbit: 355 724 597 km

-

355 724 597 km / 2 596 125 km ≈ 137.02

Put differently, the distance covered by the Earth in 1 TGY (25344 solar years) is about 137 times longer than the distance covered by the Sun in one day. Or you could say that for each daily rotation of the Earth, the Sun covers a distance corresponding to 1/137 of the Earth’s orbital circumference.

But why bother about a seemingly random number like 137? Well, it so happens that this peculiar 1/137 ratio is one of the most hotly debated ‘mysteries’ in physics:

“Why the number 137 is one of the greatest mysteries in physics. Does the Universe around us have a fundamental structure that can be glimpsed through special numbers? The brilliant physicist Richard Feynman (1918-1988) famously thought so, saying there is a number that all theoretical physicists of worth should “worry about”. He called it “one of the greatest damn mysteries of physics: a magic number that comes to us with no understanding by man”. That magic number, called the fine structure constant, is a fundamental constant, with a value which nearly equals 1/137. Or 1/137.03599913, to be precise. It is denoted by the Greek letter alpha – α.(…) Appearing at the intersection of such key areas of physics as relativity, electromagnetism and quantum mechanics is what gives 1/137 its allure.” “Why the number 137 is one of the greatest mysteries in physics” by Paul Ratner (2018)

The ‘fine-structure constant’ has kept the world’s most eminent physicists busy for decades, including Nobel Prize winner Wolfgang Pauli (1900-1958) who was obsessed with it his whole life: “When I die my first question to the Devil will be: What is the meaning of the fine-structure constant?” - Pauli joked. Physicist Laurence Eaves, a professor at the University of Nottingham, would choose the number 137 to signal to aliens as an indication that humanity has some measure of mastery over the planet and is familiar with quantum mechanics. He believes the hypothetical aliens would be aware of the significance of the number as well, especially if they developed advanced sciences. “Fine Structure Constant” - a video featuring Professor Eaves)

Without delving too deeply into nuclear physics, a domain beyond the scope of this book, suffice it to remind the reader that electrons have long been thought to revolve around the atomic nucleus “much like planets orbit the Sun”, as Niels Bohr would have put it when he proposed his famous model of the atom in 1912. Today, the orbital velocity of electrons is believed to be 1/137 the speed of light. Theoretical physicists refer to this perplexing and relatively recently discovered 1/137 ratio as the ‘fine-structure constant’ or the ‘coupling constant’ (or simply ‘Alpha’) of the electromagnetic force that binds atoms together.

“Perhaps the most intriguing of the dimensionless constants is the fine-structure constant α. It was first determined in 1916, when quantum theory was combined with relativity to account for details or ‘fine structure’ in the atomic spectrum of hydrogen. In the theory, α is the speed of the electron orbiting the hydrogen nucleus divided by c. It has the value 0.0072973525698, or almost exactly 1/137. Today, within quantum electrodynamics (the theory of how light and matter interact), α defines the strength of the electromagnetic force on an electron. This gives it a huge role. Along with gravity and the strong and weak nuclear forces, electromagnetism defines how the Universe works. But no one has yet explained the value 1/137, a number with no obvious antecedents or meaningful links.” “Light Dawns” by Sidney Perkowitz (2015)

The ‘magic’ 137 number is also described as a constant related to an electron’s magnetic moment, or the ‘torque’ that it experiences in a magnetic field. In the TYCHOS, the Sun may be conceptualized as the ‘electron’ that revolves around, and in the opposite direction of, the spinning ‘nucleus’, which may be envisioned as ‘the central magnetic field’ constituted by the Earth’s PVP orbit. As shown at the beginning of this section, for every diurnal rotation of the Earth, the Sun moves by a distance corresponding to 1/137 of the PVP orbit’s circumference. Could this be entirely accidental? Or could it perhaps be a precious clue towards a better understanding of the ‘magic’ 137 number? There certainly couldn’t be a more fascinating prospect than discovering that the microcosm and the macrocosm are governed by the same universal constant.

Fig. 21.11 Conceptually, a light beam travelling around the PVP orbit in one day will cover 137 times the distance covered daily by the Sun. In atomic physics, electrons are reckoned to travel 137 times slower than light.

Fig. 21.11 Conceptually, a light beam travelling around the PVP orbit in one day will cover 137 times the distance covered daily by the Sun. In atomic physics, electrons are reckoned to travel 137 times slower than light.

Prof. John K. Webb of the University of New South Wales, Australia, has committed much effort to exploring the secrets of the ‘fine-structure constant’:

“There’s something stange going on… a spatial variation… because when we look in one direction of the Universe we see Alpha being a little bit smaller - and when we look in exactly the opposite direction it’s a little bit bigger.” Source: “Is Our Entire Universe Held Together By One Mysterious Number?”

In another speech, Webb muses about the perplexing issue of the observed, spatially opposed variations of the constant Alpha. He explains that the two sets of data he uses are collected by two of the world’s largest observatories (the Keck Observatory in Hawaii and the VLT in Chile), located practically on opposite sides of the planet: “Using the Keck telescope, it seems as if Alpha decreases, while using the VLT, it seems as if Alpha increases. Very strange…” Once more, the TYCHOS model offers a straightforward explanation for this “very strange” phenomenon: since the Earth slowly proceeds through space at 1.6 km/h along a virtually straight line rather than around an annual circle, the stars ‘to our left’ will seem to move in the opposite direction of the stars ‘to our right’. This is also why stars exhibit both ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ parallax, as will be thoroughly explicated in Chapter 25. But the best is yet to come with regard to Prof. Webb’s rigorous research:

The Wikipedia entry on the ‘fine-structure constant’ informs us that Webb’s first, groundbreaking findings (published in 1999) described a minuscule variation in the Alpha constant. This variation in the constant amounted to about 0.0000057 of the 137 value, which allows us to the following math:

-

0.0000057 is tantamount to 0.0000041% of 137.03599913

-

Circumference of the Sun’s orbit: 939 943 910 km

-

0.0000041% of 939 943 910 km amount to 38.537 km

-

Daily displacement of the Earth in the TYCHOS: 38.428 km

So could this minuscule variation in the constant detected by Webb possibly be related to the Earth’s daily motion? If not, we shall just have to chalk this up to yet another extraordinary coincidence, the odds of which you may choose to characterize as ‘astronomical’ or ‘atomical’.

In conclusion, as viewed within the TYCHOS model, the 1/137 ratio would not only be ‘reflected’ by the Sun’s daily motion in relation to the ‘nucleus’ of the system (represented by the Earth’s PVP orbit), but its tiny observed variation can also be shown to be ascribable to the daily motion of the Earth itself. One can only marvel at the explanatory power of the TYCHOS model which, as we progressively test its tenets against empirical observations, would even appear to extend to arcane quandaries of physics, such as the mysterious 1/137 fine-structure constant, a subject matter widely considered to be “one of the greatest unsolved problems in physics” “Why Is 1/137 One of the Greatest Unsolved Problems In Physics?” - by PBS SPace Time

At this juncture, it would appear that we have a solid groundwork with which we can start to dismantle the heliocentric theory once and for all. However, we will first need to demonstrate, in methodical fashion, that the last centuries’ most celebrated ‘science icons’ were ignorant of the true geometric configuration of our Solar System. Some are still hailed today for having “definitively proven that Earth revolves around the Sun”, despite the absence of any experimental evidence in support of this contention. Two names come to mind: James Bradley and Albert Einstein. In the next chapter, we shall see how the convoluted theories put forth by these two science celebrities were founded upon illusory observations, fallacious interpretations and—quite literally—thin air.