Chapter 13: Our system’s ‘central driveshaft’: the Moon

13.1 Introduction

There is very strong evidence that our lunar satellite—the Moon—acts as a sort of ‘central driveshaft’ for the entire solar system. If this can be proven to be so, we can all say good-bye to heliocentrism. For Copernican astronomers, it simply makes no sense that our Moon would play such a central role in the solar system, but if we envision the Moon as a body revolving around Earth, at the center of the Sun-Mars binary system, things take on a very different appearance.

In the TYCHOS model, our Moon has an average synodic period of 29.2194 days, but for simplicity’s sake we shall use the rounded figure of 29.22 days. I will refer to this period as the Moon’s true mean synodic period (TMSP). It turns out that the synodic periods of all our system’s bodies are exact multiples of the Moon’s TMSP. This stands in stark contrast to the Copernican notion that the Moon is just a random peripheral appendage circling around Earth. But let us examine the numbers:

• Orbital resonance pattern of the Moon, Mercury, Venus and Mars: 1 : 4 : 20 : 25

• Sum of these four resonance ratios: 1 + 4 + 20 + 25 = 50

• The Sun-Moon orbital resonance ratio: 50 / 4 = 12.5

Moon: 1 TMSP (1 x 29.22) 29.22 days

Mercury: 4 TMSP (4 x 29.22) 116.88 days

Venus: 20 TMSP (20 x 29.22) 584.4 days

Mars: 25 TMSP (25 x 29.22) 730.5 days

Sun: 12.5 TMSP (12.5 x 29.22) 365.25 days

This lunar orbital resonance rule also applies to the so-called outer planets:

Jupiter: 150 TMSP (150 x 29.22) 4383 days - or 12 solar years

Saturn: 375 TMSP (375 x 29.22) 10957.5 days - or 30 solar years

Uranus: 1050 TMSP (1050 x 29.22) 30681 days - or 84 solar years

Neptune: 2062.5 TMSP (2062.5 x 29.22) 60266.25 days - or 165 solar years

Pluto: 3100 TMSP (3100 x 29.22) 90582 days - or 248 solar years

In other words, the synodic periods of all the bodies in our solar system are ‘round’ multiples of the Moon’s TMSP of 29.22 days!

As we shall see, the only reason why this perfect clockwork, encompassing all our system’s bodies revolving at exact multiples of the Moon’s TMSP, has gone unnoticed by astronomers throughout the ages is, essentially, Earth’s previously unimagined ‘snail-paced’ motion around the PVP orbit. Unless one is aware of this motion, all earthly determinations of the orbital periods of our system’s bodies will be ever so slightly in error. However, ordering the pieces within the TYCHOS model’s geometry unveils a breathtaking cosmic harmony.

Fig. 13.1 The Moon is manifestly at the center of our solar system, acting as a sort of ‘pacemaker’ or ‘central driveshaft’ for the entire system.

Fig. 13.1 The Moon is manifestly at the center of our solar system, acting as a sort of ‘pacemaker’ or ‘central driveshaft’ for the entire system.

At this point, some may object that the Moon’s synodic period is 29.53 days, not 29.22 days. That is indeed what an earthly observer may hastily conclude. Yet, that value will depend on the particular time window chosen to compute the Moon’s average long-term (secular) synodic period. In fact, only by spending centuries of careful observation will a correct average value of the Moon’s synodic period be obtained. That is just what the meticulous Aztecs appear to have done, as their famed Toltec Sunstone suggests.

“To summarize, then, the Toltec Sunstone is an image of the motion of Venus, consisting of two hundred sixty, 8-year, periods, divided up into forty 52 year periods, as encoded in the ring of 40 quincunxes surrounding the ring of 20-day names. Each 8-year period of 2922 days is counted by a rotation of the 20 day-sign ring, where each day-sign actually represents one month of 29.22 days. Therefore, one complete revolution of the day-sign ring counts 20 x 29.22 days, or the average Venus year of 584.4 days. Five of these revolutions, each uniquely named in the center quincunx, counts 100 x 29.22 = 2922 days, or five Venus years of 584.4 days each, which is equivalent to eight years of 365.25 days each. By assigning the 20 day-sign symbols to a lunar month of 29.22 days, each month of the Venus year has a unique name, just as the twelve months of our Earth year has, making it easy for the public to mark the months, or ‘moons,’ as they went by.” p.6, “The Aztec Calendar Stone is not Aztec and it is not a Calendar” by Douglas L. Bundy (2012)

For instance, if you choose a time window of 65 years +/- 2 days, a little-known interval at both ends of which the Moon will realign with the Sun, you will conclude that the Moon’s average synodic period is 29.53 days. Simply put, 65 solar years of 365.25 +/- 2 days equals ~23743 days. If we divide 23743 days by 67 (the number of possible integer lunar years in 65 years), we obtain 354.373 days. Therefore, one average long empiric synodic interval (ESI) of the Moon will compute to ~29.53 days (354.373 / 12).

On the other hand, if you choose a time window of 19 years (the Metonic cycle, a well-known interval at both ends of which the Moon will realign with the Sun), you would conclude that the Moon’s average period is 28.91 days. Simply put, 19 solar years of 365.25 days equals 6939.75 days. If we divide 6939.75 days by 20 (the number of possible integer lunar years in 19 years), we obtain 346.98 days. Therefore, one average short ESI of the Moon will compute to 28.915 days (346.98 / 12).

However, the Aztecs were smart enough to average the long and short ESIs to obtain a more accurate long-term TMSP :

• 29.53 + 28.915 = 58.445

• 58.445 / 2 ≈ 29.22 days (our TMSP)

The Moon also has a little-known 8-year cycle as it very nearly realigns with the Sun every 2922 +/-1.5 days. This number corresponds to 100 revolutions of 29.22 days (2922 days, or 8 solar years). Notably, the Moon’s 8-year cycle mirrors Venus’ 8-year cycle of 2922 days (5 synodic periods of 584.4 days).

Thus, our TMSP of 29.22 days can be considered the ‘master coefficient’ of our solar system. The higher and lower values observed (29.53 days and 28.91 days) are simply long-term fluctuations caused by the eccentricity of the Moon’s orbit and the 1-mph motion of the Earth-Moon system as it proceeds along the PVP orbit. Since the Earth-Moon system revolves in the opposite direction of the Sun, their respective revolutions will be opposed or co-directional, depending on the time of year. This explains the illusion of the Moon accelerating and decelerating, and its apparently variable synodic periods.

Fig. 13.2 As the Earth-Moon system proceeds at snail pace along the PVP orbit, the Moon’s speed will appear to alternately increase and decrease very slightly. More precisely, its synodic period will be shorter in the ‘upper half’ (pink section) and longer in the ‘lower half’ (green section). The eccentricity of the Moon’s orbit also contributes to these variations, but its orbital speed remains constant and its mean synodic period is ≈29.22 days.

Fig. 13.2 As the Earth-Moon system proceeds at snail pace along the PVP orbit, the Moon’s speed will appear to alternately increase and decrease very slightly. More precisely, its synodic period will be shorter in the ‘upper half’ (pink section) and longer in the ‘lower half’ (green section). The eccentricity of the Moon’s orbit also contributes to these variations, but its orbital speed remains constant and its mean synodic period is ≈29.22 days.

13.2 The Moon-Sun ‘synchronicities’

A string of remarkable ‘synchronicities’ emerge when comparing the respective rotations and revolutions of Earth, the Sun and the Moon. They are remarkable in the sense that, if viewed through Copernican lenses, they would be regarded as highly improbable coincidences. After all, if Earth, with its Moon, is just one of several planets circling the Sun, one would hardly expect these three separate celestial bodies to display ‘commensurate’ or ‘resonant’ gyrational periods.

Firstly, one has to wonder why the Sun rotates around its axis in just about the same amount of time (~27.3 days) our Moon uses to complete one orbit.

“The Carrington rotation number identifies the solar rotation as a mean period of 27.28 days, each new rotation beginning when 0° of solar longitude crosses the central meridian of the Sun as seen from Earth.” p.55, “The Sun and How to Observe It” by Jamey L. Jenkins (2009)

To my best knowledge, this remarkable synchronicity between the Sun’s rotation and the Moon’s sidereal revolution has never been pointed out, let alone discussed, in the astronomy literature.

Fig. 13.3 The Sun’s 27.3-day period explained.p.13, “Equatorial Electrojet” - by C Agodi Onwumechikli (1998)

Fig. 13.3 The Sun’s 27.3-day period explained.p.13, “Equatorial Electrojet” - by C Agodi Onwumechikli (1998)

Fig. 13.4 The Sun and Moon’s 27.3-day synchronicity, as viewed in the Copernican model.

Fig. 13.4 The Sun and Moon’s 27.3-day synchronicity, as viewed in the Copernican model.

Figure 13.4 is a screenshot from the heliocentric Scope simulator. Note what an extraordinary thing it would be, as viewed under the Copernican model, for our Moon to return facing the same star every 27.3 days (as it does), i.e., in the same time period employed by the Sun to rotate around its own axis. And all this, while the Earth-Moon system would hurtle around the Sun at Mach 90, covering some 70 million km in 27.3 days (or roughly 1/13 of its annual revolution).

Fig. 13.5 The Sun and Moon’s 27.3-day synchronicity, as viewed in the TYCHOS model.

Fig. 13.5 The Sun and Moon’s 27.3-day synchronicity, as viewed in the TYCHOS model.

Heliocentrists might rightfully wonder why only one of the hundreds of moons in our Solar System (Jupiter’s moons, Saturn’s moons, etc.) would be so fine-tuned to the Sun. But if the Moon is instead central to the Sun’s orbit, as posited by the TYCHOS model (Figure 13.5), this particularity begins to make sense, both intuitively and philosophically. So let us now compare the respective rotational speeds of the Sun, the Earth and the Moon.

These ‘resonances’ and ‘synchronicities’ would have no reason to exist if our planet were simply racing around the Sun in the Copernican third lane. However, the privileged barycentric position within the Sun’s orbit assigned to the Earth-Moon system in the TYCHOS makes the affair a lot less mysterious. This should gradually become apparent even to the most sceptical reader.

Sun’s rotational speed: 6675 km/h

Earth’s rotational speed: 1670 km/h

Moon’s rotational speed: 16.65 km/h

Orbital speed of Earth = 1.601669 km/h

From the above data we can conclude the following:

• The Sun’s rotational speed is near-exactly 4 times the Earth’s rotational speed.

• The Sun’s rotational speed is near-exactly 400 times our Moon’s rotational speed.

• Earth’s rotational speed is near-exactly 100 times our Moon’s rotational speed.

• In the TYCHOS, the Moon’s rotational speed is about 10 times the orbital speed of Earth.

13.3 The heliocentric model’s ‘lunatic’ sidereal period

For this next argument against the Copernican theory, keep in mind that if the Earth-Moon system really travelled around the Sun at 107226 km/h, it would move by about 70 million km every 27.3 days. Yet, in actual observation, our Moon lines up with the very same star at intervals of 27.3 days. It should be obvious that this easily observable pattern is incompatible with the Copernican model, which has Earth and the Moon circling the Sun in a 300 Mkm wide orbit. Now let us see how the Copernican theory fares in an imaginary ‘real-world’ scenario we can easily relate to:

Imagine a prisoner held on a ship which perpetually travels around a huge, circular route. It takes 365 calendar days for the ship to complete this circle, and the prisoner can sense the ship is moving at a constant speed. His only equipment is a magnetic compass. One night, he sees through his porthole a distant lighthouse and estimates its location as being due north in relation to the middle of the ship’s circular path. He really wants to figure out how long it takes for the ship to complete its circular journey so he raises his forefinger in front of his nose and patiently starts counting the days needed for the lighthouse to align again with his forefinger.

Should we expect the man to see that lighthouse regularly lining up with his finger every 27.3 days? Of course not. Yet, this is exactly what is implied by the heliocentric theory. Figure 13.6 shows how the Copernican model envisions the Moon aligning with a given star every 27.3 days, in spite of the Earth’s alleged orbital motion around the Sun:

Fig. 13.6 The absurdity of the heliocentric model’s geometry with respect to the Moon’s 27.3-day sidereal period.

Fig. 13.6 The absurdity of the heliocentric model’s geometry with respect to the Moon’s 27.3-day sidereal period.

To further illustrate this Copernican aberration of optical perspective, here is how the SCOPE Solar System simulator depicts the solar eclipse of 20 March 2015 at 10:00 UTC (which I personally viewed from Rome) compared to a subsequent position of the Earth-Moon pair (27.3 days later, on 16 April 2015 at 17:00 UTC). On both of these dates, the Moon conjuncted with the star Vernalis:

Fig. 13.7 During the solar eclipse of 20 March 2015, the Moon and the Sun were both aligned with the star Vernalis. 27.3 days later, the Moon was again aligned with the star Vernalis.

Fig. 13.7 During the solar eclipse of 20 March 2015, the Moon and the Sun were both aligned with the star Vernalis. 27.3 days later, the Moon was again aligned with the star Vernalis.

In fact, the entire Copernican theory relies on the misconception that very distant stars will not be affected by parallax. Allow me now to state the obvious with regard to the basic laws of perspective underpinning the concept of parallax:

YES: A very small parallax will indeed occur between two very distant objects, such as two unequally distant stars.

NO: A relatively nearby object, such as the Moon, cannot possibly remain aligned with any distant star whilst an earthly observer and the nearby object (in this case, our Moon) both drift laterally, and perpendicularly to that star’s location, for several million kilometers.

It is truly astonishing that the Copernican theory has survived, largely unchallenged, for over 400 years!

13.4 About the saros and exeligmos cycles

“The saros is a period of approximately 223 synodic months (approximately 6585.3211 days, or 18 years, 11 days, 8 hours), that can be used to predict eclipses of the Sun and Moon.” “Saros astronomy” - Wikipedia

Saros cycle = 6585.3211 days

Full moon cycle = 411.78433 days

6585.3211 / 411.78433 ≈ 15.992 ≈ 16 full moon cycles

Now, the 18-year Saros cycle is just part of a longer and more complete triple Saros cycle known as an ‘exeligmos’. An exeligmos comprises approximately 19756 days, corresponding to nearly 48 full moon cycles: 19756 / 411.78433 days ≈ 48 (or 3 x 16).

“An exeligmos (Greek: ἐξέλιγμος — turning of the wheel) is a period of 54 years + 33 days that can be used to predict successive eclipses with similar properties and location. For a solar eclipse, after every exeligmos a solar eclipse of similar characteristics will occur in a location close to the eclipse before it. For a lunar eclipse the same part of the earth will view an eclipse that is very similar to the one that occurred one exeligmos before it.” “Exeligmos” - Wikipedia

As a 54.1-year exeligmos is completed, any lunar or solar eclipse will recur close to the geographic location it occurred 54.1 years earlier, albeit approximately one month later. The lunar and solar eclipses are therefore actually seen to ‘precess’ by 1/12 against the firmament from one exeligmos to the next.

One could say that the exeligmos is the ‘master cycle’ of the Moon’s complex dance around Earth, at the completion of which the Moon returns to the same position with respect to the Sun. This 54.1-year cycle has long remained an unsolved riddle. Since the exeligmos has been observed for millennia, mainstream astronomers can only acknowledge its existence as a matter of fact, yet no attempt to explain it has materialized in the astronomy literature.

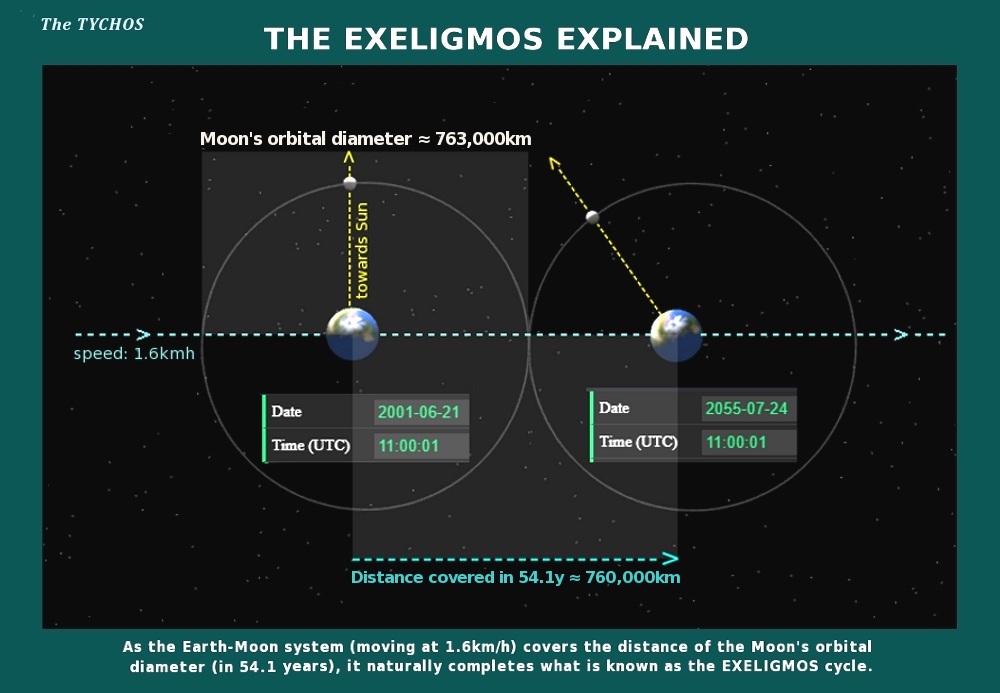

We shall now see how the TYCHOS model accounts for the peculiar kinematics responsible for the exeligmos cycle. Considering the daily displacement of Earth (38.428 km), moving at 1.6 km/h, the distance covered by the Earth-Moon system in the course of an exeligmos cycle turns out to be very close to the orbital diameter of the Moon (~763000 km).

→ Duration of 1 exeligmos = 19756 days

→ Daily displacement of Earth along the PVP orbit = 38.428 km

→ 19756 x 38.428 = 759184 km

This is only about 3816 km less than the Moon’s orbital diameter. However, it is reasonable to assume this discrepancy can be accounted for by the diameter of the Moon itself (3476 km). In short, it would seem intuitively logical that an exeligmos cycle will be completed when the Earth and the Moon have together covered a distance almost equal to the Moon’s orbital diameter of 763000 km. Let’s see how this 54.1-year period would look like in the TYCHOS model. As ever, an image speaks more than a thousand words:

Fig. 13.8 As the Earth-Moon system (moving at ∼1.6km/h) covers the distance of the Moon’s orbital diameter (in 54.1 years), it naturally completes what is known as the ‘exeligmos cycle’.

Fig. 13.8 As the Earth-Moon system (moving at ∼1.6km/h) covers the distance of the Moon’s orbital diameter (in 54.1 years), it naturally completes what is known as the ‘exeligmos cycle’.

It would seem the mysterious exeligmos is not so enigmatic after all, provided we use the right configuration of the solar system. The exeligmos cycle is a natural consequence of the Earth-Moon system’s 1.6 km/h motion: every 54.1 years, the system will cover a distance equal to the Moon’s orbital diameter and, therefore, the Moon will return to an Earth-Moon-Sun alignment similar to the one observed 54.1 years (19756 days) earlier. Simple as that!

We can use the Tychosium simulator to verify the exactitude of the exeligmos’ 19756-day period. For instance, the solar eclipse I witnessed in Rome on 20 March 2015 at 10:00 UTC will recur exactly 19756 days later, on 21 April 2069 at 10:00 UTC.

Finally, let us verify whether the TYCHOS model can mathematically reconcile the exeligmos cycle with the TYCHOS Great Year:

→ TGY (Tychos Great Year) = 25344 solar years

→ Circumference of the PVP orbit = 355 724 597 km.

→ Distance covered by the Earth-Moon system over 1 exeligmos = 759184 km.

→ Number of exeligmoi in 1 TGY = 355 724 597 / 759184 ≈ 468.5

→ 468.5 x 54.1 years = 25345.85 years ≈ 1 TGY

Hence, the exeligmos cycle turns out to be in perfect agreement with the Earth-Moon system’s orbital speed of ~1.6 km/h. The odds of all this being entirely coincidental are, you may admit, ‘astronomical’. And thus the TYCHOS elucidates the Moon’s ‘master cycle’ of 54.1 years

13.5 The Moon’s 76-year Callippic cycle

Named after the Greek astronomer Callippus (~330 BC), the Moon’s Callippic cycle of 76 years (27759 days) allows for greater accuracy than the so-called Metonic lunar cycle of 19 years. Indeed, the Moon returns to almost the exact same celestial longitude in the sky at intervals of 27759 days. For instance, using the Tychosium simulator, the Moon may be seen to return near-exactly to 6 h of RA on the two dates below, separated by 27759 days:

-

2001-06-21 (12:00:00 UTC)

-

2077-06-20 (15:00:00 UTC).

Callippic cycle = 27759 days The Moon’s TMSP = 29.22 days 27759 / 29.22 = 950 TMSP

Another interesting aspect of our Moon’s Callippic cycle is its officially estimated ‘error rate’ of 1 day for every 553 years.

“The (Callippic) cycle’s error has been computed as one full day in 553 years.” “Callippic cycle” - Wikipedia

When viewed in the TYCHOS model, this Callippic ‘error rate’ may be interpreted as follows: As will be expounded in Chapter 21, the Sun’s annual ‘error rate’ in relation to our earthly clocks amounts to about 31.4 min, as the Sun is empirically observed to oscillate from east to west around its ‘mean zenith’ by a little more than half an hour every year. However, thanks to the ingenious gimmick known as the Equation of Time, our clocks, which tick at a constant rate, are nonetheless able to give us a useful approximation of the passage of time—accurate enough for our daily purposes.

Now, we see that 31.4 min amounts to 2.18% of 1440 min (the complete celestial sphere). Similarly, 553 years amounts to about 2.18% of 25344 years (The duration of 1 TYCHOS Great Year). It would therefore be reasonable to assume that the ‘error rate’ of the Callippic cycle is actually the lunar equivalent of the annual ‘error rate’ of the Sun.

13.6 Testing the Moon’s perigee precession in the TYCHOS

Fig. 13.9 The current astronomical understanding of the Moon’s perigee precession, or ‘apsidal precession’

Fig. 13.9 The current astronomical understanding of the Moon’s perigee precession, or ‘apsidal precession’

“The lunar perigee precesses in the direction of the moon’s orbital motion at the rate of n−n˜ = 0.1114 ◦ per day, or 360◦ in 8.85 years.” “A Modern Almagest: An Updated Version of Ptolemy’s Model of the Solar System” by Richard Fitzpatrick (2010)

• Daily precession of the Moon’s perigee = 0.1114°

• Annual precession of the Moon’s perigee = 0.1114° x 365.25 = 40.68885° (146480″)

• Time to complete a full cycle = 360° / 0.1114° ≈ 3231.5978 days (8.8476327 years)

A comparison of this empirically observed annual precession of the Moon’s perigee with our annual constant of precession (ACP) reveals that the Moon’s perigee precesses 2864.5 times faster than the firmament.

→ ACP = 51.136″

→ 146480 / 51.136 ≈ 2864.5

→ TGY = 25344 solar years

→ ACP x TGY = complete precession of the firmament (360°)

→ TMSP = 29.22 days

→ TMSPs in a complete perigee precession => 3231.5978 / 29.22 ≈ 110.5954

→ TMSPs in 1 TGY => 110.5954 x 2864.5 ≈ 316800 (i.e. 9 256 896 / 29.22)

In other words, the Moon’s empirically observed perigeal precession is in excellent agreement with the TYCHOS Great Year (25344 solar years, or 9 256 896 days).

13.7 The Moon’s apsidal precession ‘mirrors’ the EAM

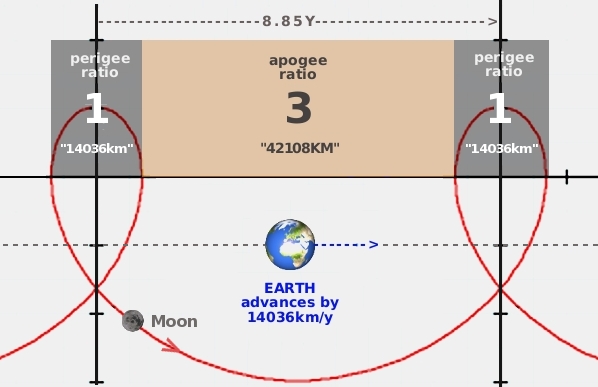

What follows is nothing short of astounding: using the TYCHOS model, the Moon’s so-called apsidal precession can be shown to ‘mirror’ Earth’s annual motion (EAM) of 14036 km. In simple words, the apsidal precession is the gradual rotation of the line connecting the apsides of an astronomical body’s orbit (referred to as the ‘line of apsides’). The apsides of the Moon are the orbital points closest (perigee) and farthest (apogee) from Earth.

We have just seen that the observed angular rate of the Moon’s perigee precession nicely agrees with the TGY. We shall now look at two other aspects of the Moon’s oscillations, namely the observed magnitude (in km) of the Moon’s perigee precession and the observed magnitude (in km) of its full apsidal precession (from perigee to apogee). The Moon completes a full apsidal precession in ~8.85 years.

Let us first have a look at how the Moon’s perigee and apogee are conventionally illustrated. Figure 13.10 is a classic diagram one can find in astronomy books depicting the minimum and maximum Earth-Moon distances (perigee vs. apogee):

Fig. 13.10 Schematic view of the orbit of the Moon as seen from above. The eccentricity is overemphasised, and size and distance are scaled differently. (Source: http://beltoforion.de )

Fig. 13.10 Schematic view of the orbit of the Moon as seen from above. The eccentricity is overemphasised, and size and distance are scaled differently. (Source: http://beltoforion.de )

The Astro Pixels database features annual charts of the Moon-Earth distances for the lunar perigee and apogee transits, and this may well be of interest to the TYCHOS model. As I consulted their detailed chart of the Moon’s perigee transits, my attention was naturally drawn to this statement regarding the long-term (secular) average minimum and maximum lunar perigee distances:

“Over the 5000-year period from -1999 to 3000 (2000 BCE to 3000 CE), the distance of the Moon’s perigee varies from 356,355 to 370,399 km.” AstroPixels.com

So let’s see: the difference between 356355 km and 370399 km is 14044 km. This distance is almost identical to the EAM. In fact, by carefully consulting these lunar perigee charts, one can easily verify that the Moon’s perigee regularly oscillates back and forth every solar year by an average distance of approximately 14000 km.

Fig. 13.11 Graphic showing how the Moon’s perigee will oscillate radially by about 14000 km, arguably in harmony with the EAM.

Fig. 13.11 Graphic showing how the Moon’s perigee will oscillate radially by about 14000 km, arguably in harmony with the EAM.

But it gets even more exciting! This is what the Astro Pixels website has to say about the mean variations between the lunar perigee and apogee:

“The Moon’s distance from Earth (center-to-center) varies with mean values of 363,396 km at perigee (closest) to 405,504 km at apogee (most distant).” Astropixels.com

→ 405504 km - 363396 km = 42108 km

→ 3 EAM = 3 x 14036 km = 42108 km

This leads us to a most sensational realization: our Moon’s apsidal precession is a perfect ‘reflection’ of the EAM, as proposed by the TYCHOS. Since the Moon revolves around Earth, while Earth itself advances in space, the lunar trajectory will be a looping geometrical curve known as a trochoid. The longer and shorter loops of this prolate trochoid exhibit a 3:1 ratio and, in fact, we just saw that the Moon’s apogee and perigee exhibit just such a 3:1 ratio (42108 / 14036 = 3). One truly couldn’t wish for a better confirmation of the TYCHOS’ proposed earthly rate of motion. Please make a mental note of that trochoidal 3:1 ratio: we will encounter it again further on in the book

The conceptual graphic in Figure 13.12 illustrates the basic geometry of the Moon’s apsidal precession. Of course, the Moon doesn’t complete just one such trochoid loop in 8.85 years, but the diagram should help envision the peculiar geometrics at play, particularly with respect to the above-mentioned 3:1 ratio.

Fig. 13.12 A conceptual diagram illustrating the 3:1 ratio of the Moon’s trochoidal path around the moving Earth

Fig. 13.12 A conceptual diagram illustrating the 3:1 ratio of the Moon’s trochoidal path around the moving Earth

I was then curious to see whether this trochoidal pattern could be reproduced in the Tychosium 3D simulator over an extended period, plotting a hypothetical time-lapse ‘picture’ of our Moon’s long-term orbital progression. I figured that, in order to ‘see it’, I needed to increase Earth’s speed in the simulator by a few orders of magnitude. This was the result:

Fig. 13.13

Fig. 13.13

In this chapter I have highlighted a number of aspects concerning our lunar satellite:

• Its role as the ‘central driveshaft’ or ‘pacemaker’ of our solar system

• The synchronicity of its orbital revolutions with the Sun’s axial rotations (~27.3 days)

• The absurdity of the sidereal period kinematics proposed by the heliocentric theory

• The concordance of its exeligmos cycle with the orbital speed of the Earth-Moon system in the TYCHOS

• The concordance of its Callippic cycle with the TMSP proposed by the TYCHOS (29.22 days)

• The most remarkable commensurability, at a 3:1 ratio, between its apsidal precession and the EAM proposed by the TYCHOS (14036 km)

The Moon’s so-called ‘librations’ in longitude and latitude are also accounted for by the TYCHOS model’s geometry, what with the Moon’s eccentric (not elliptical) orbit and the 6.7° inclination between the Moon’s axis of rotation and its orbital plane around Earth. This is why we can actually observe up to 59% of the lunar surface―an undisputed, empirically observable fact:

“Over time, slightly more than half (about 59% in total) of the Moon’s surface is seen from Earth due to libration.” “Libration” - Wikipedia

However, the complex orbital behaviour of our Moon has never been fully understood or justified, in spite of it being the body closest to our planet. The next chapter will therefore take a closer look at the subtler aspects of our Moon’s long-term motions which, notoriously, caused Sir Isaac Newton many a headache. As we shall see, the TYCHOS model can elucidate several other aspects of the Moon’s puzzling behaviour which, as famously stated by Pierre-Simon Laplace, “failed to conform in all respects with the laws of universal gravity”.