Chapter 4: Introducing the TYCHOS model

4.1 A general overview

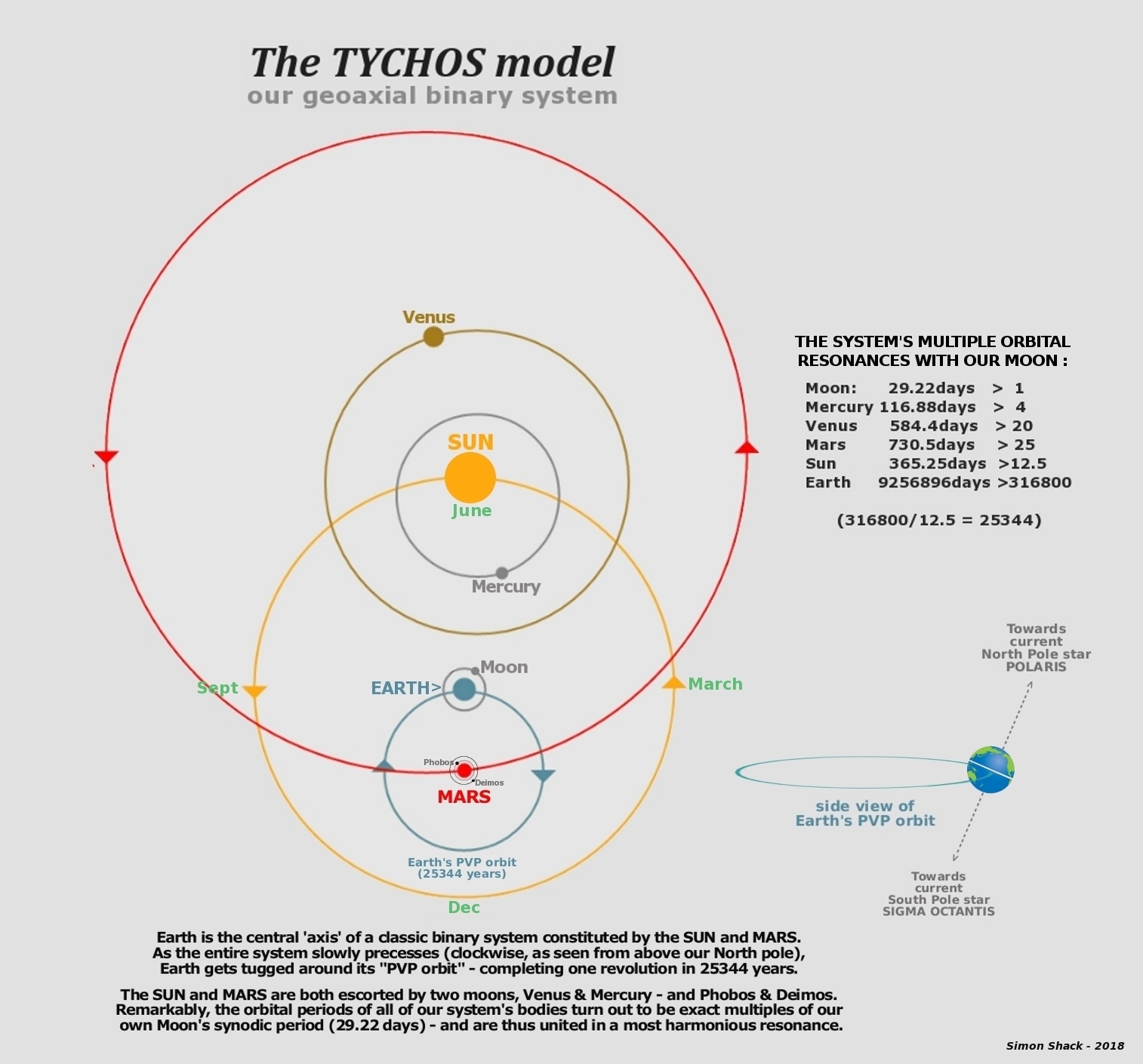

The Sun and Mars are the main players of what I have called our ‘geoaxial binary system’. At or near its barycenter, we find Earth and our Moon, while the Sun (escorted by its two moons, Mercury and Venus) and Mars (escorted by its own two moons, Phobos and Deimos) perform their binary dance around our planet. It is Earth’s physical motion around its Polaris-Vega-Polaris orbit (PVP, for short) that causes our North stars to change over time—a very slow process commonly known as the Precession of the Equinoxes.

Fig. 4.1 Overview of the TYCHOS, our Geoaxial Binary System

Fig. 4.1 Overview of the TYCHOS, our Geoaxial Binary System

In the TYCHOS, Earth is inclined at about 23.4° in relation to its orbital plane, yet at all times its northern hemisphere remains tilted ‘outwards’, i.e. towards the external circuit of the Sun. The Sun revolves once a year around Earth, traveling at 107226 km/h (this is the orbital speed attributed to Earth by Copernican astronomers). Every 2.13 years, its binary companion, Mars, reconjuncts with the Sun at either side of Earth (the above graphic shows Mars transiting in so-called ‘opposition’). Mars is not a third moon of the Sun, as some commentators have suggested, because it is the only body in our cosmic neighbourhood whose orbit has it transiting alternately in opposition to and in conjunction with the Sun. The only reason Mars may seem problematic to reconcile with the popular notion of ‘binary motion’ is that its orbit is not locked in a 1:1 ratio with the Sun, but in a 2:1 ratio. Hence, Mars will not return in opposition every year, but only every other year or so.

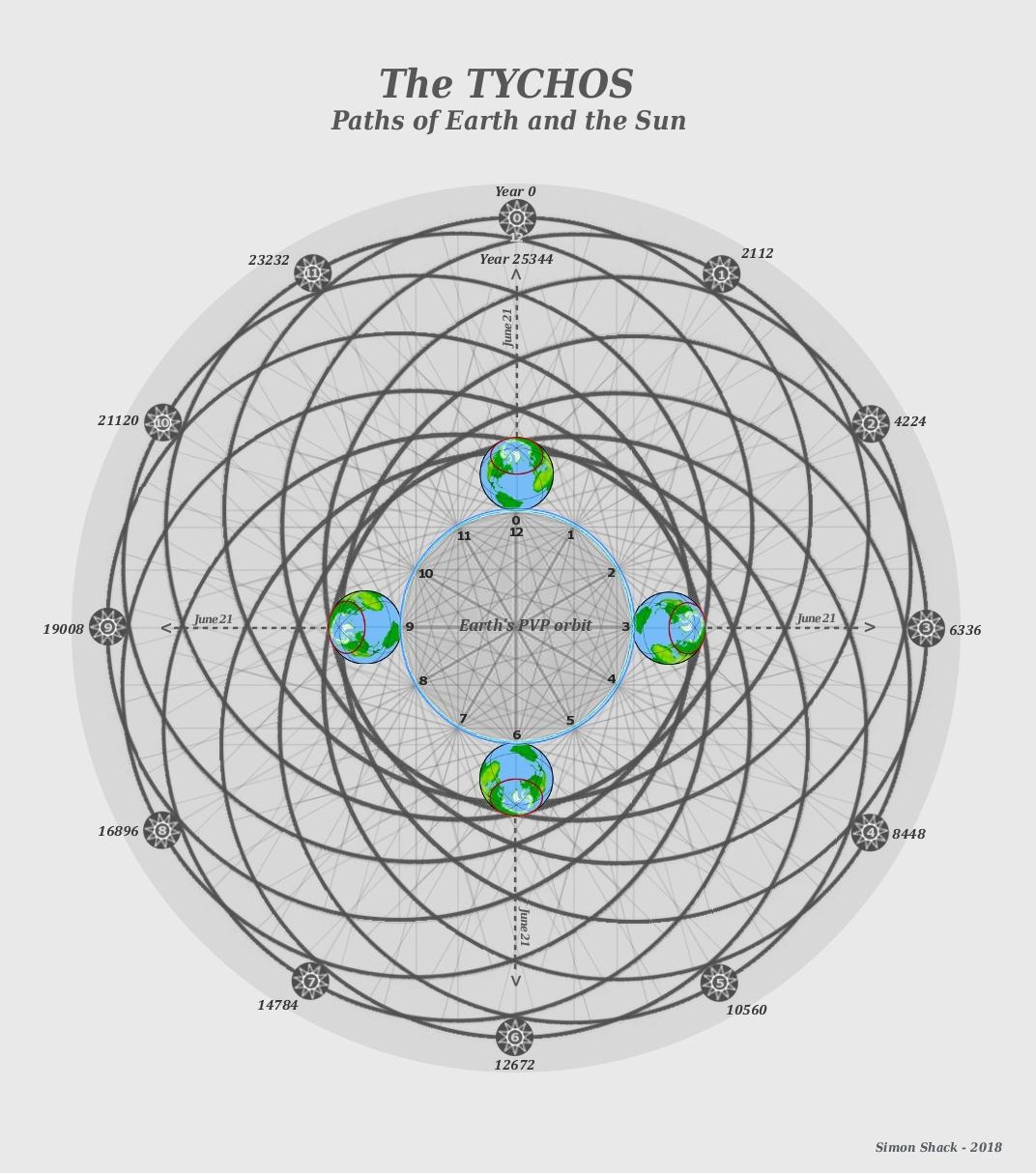

Each year, Earth moves ‘clockwise’ (as seen from above our North Pole) by 14036 kilometers along its PVP orbit—i.e. slightly more than its own diameter of 12756 km. This motion of Earth provides a perfectly simple explanation for the observed annual ‘backward’ motion of our stars referred to as the Precession of the Equinoxes. I will henceforth refer to this yearly 14036-km advancement of Earth as the EAM (Earth’s Annual Motion).

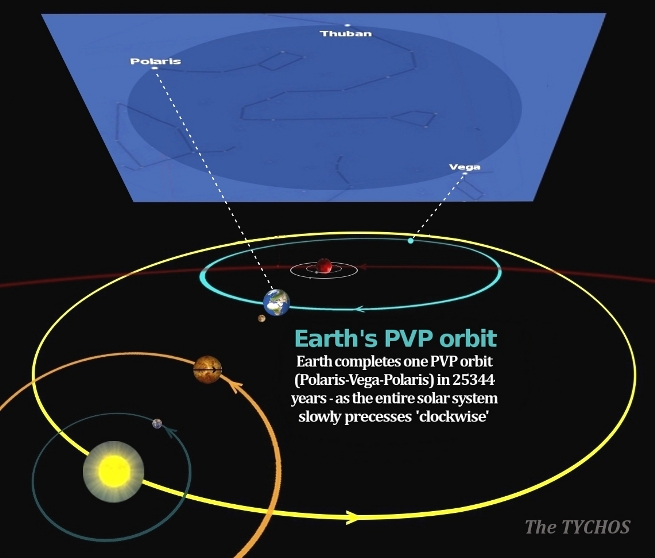

There is thus no need for Earth to “wobble around its polar axis” (also known as “Earth’s 3rd motion”) as posited by Copernican theory; nor does Earth hurtle around space at hypersonic speeds. Earth only rotates around its axis once every 24 hours at the extremely sluggish rate of 0.000694 rpm while it gently gets tugged around its orbital path at 1.6 km/h (about 1 mph), , as the entire Solar System precesses ‘clockwise’ (as viewed from above our North Pole). In such manner, Earth completes one revolution around the PVP orbit every 25344 years, a period also known as the Great Year. I submit that what I have called the PVP orbit is the missing piece of the puzzle of Tycho Brahe’s admirable geoheliocentric system. The PVP orbit will of course be thoroughly expounded and illustrated further on in this book, as it constitutes the core discovery upon which the TYCHOS model is founded.

It is essential to understand that in the TYCHOS model all the planets and moons orbit at constant speeds around uniformly circular (albeit eccentric) orbits. In other words, there never was any need for Kepler’s variable orbital speeds or for his proposed elliptical orbits—the latter being just an illusion caused by Earth’s motion around its PVP orbit. To wit, since Earth slowly proceeds along an almost straight line (over, say, 100 years) the Sun and our surrounding planets will appear to oscillate slightly back and forth. In the summer of the northern hemisphere the Sun will be moving in the opposite direction of Earth, whereas in the winter it will be moving in the same direction as Earth. Thus, the illusion of elliptical orbits is created, while other apparent speed variations are due to the fluctuating distances between Earth and the various bodies of our solar system. The circular orbits of those bodies are all eccentric, which means they are slightly off-center in relation to Earth.

This brings up the age-old question: “Orbital speeds, in relation to what?” The short answer is: in relation to the ‘fixed’ stars. Now, the stars also have motions of their own (proper motions). That is, they move ever so slightly (typically 0.1 arcsec/year) in random directions. Hence, we should be satistied that the star backdrop (the firmament) constitutes a quite reliable, near-static reference frame against which we may compute the orbital speeds of the various bodies of the solar system, provided we duly account for Earth’s own orbital motion. What is empirically observed is that all stars in the firmament drift from west to east in our skies by about 50 arcseconds a year. In the TYCHOS model, this slow 25344-year revolution of the firmament is merely the optical effect of Earth’s tranquil 1-mph motion around its PVP orbit.

Fig. 4.2 The estimation of the PVP orbit’s orbital diameter (113.2 Mkm) is illustrated in Chapter 11. Note for now that the average Mars-Earth perigee distance (i.e., as Mars transits closest to Earth) is 56.6 Mkm, or precisely the PVP orbit’s radius (113.2 / 2 = 56.6).

Fig. 4.2 The estimation of the PVP orbit’s orbital diameter (113.2 Mkm) is illustrated in Chapter 11. Note for now that the average Mars-Earth perigee distance (i.e., as Mars transits closest to Earth) is 56.6 Mkm, or precisely the PVP orbit’s radius (113.2 / 2 = 56.6).

4.2 Distances to our solar system’s bodies versus distances to the stars

Copernican astronomers use the diameter of the Earth (12756 km) as a baseline to measure the distance between the bodies of our solar system. The TYCHOS rigorously respects these universally approved measurements, but estimating the distance between the Earth and the stars is an entirely different matter. This is because astronomers have for this purpose chosen as baseline the diameter of Earth’s purported orbit around the Sun, which is claimed to be approximately 300 Mkm. Since they are using a nonexistent 300 Mkm, 6-month lateral displacement as baseline, all their calculations of Earth-star distances are grossly and systematically inflated. In the TYCHOS model, Earth moves by only 7018 km every six months, not by 300 000 000 km. This means that the stars are over 42600 times closer to us than currently claimed—a notion Tycho Brahe would undoubtedly have welcomed and supported. In any case, the notion that stars can be located several thousand light years away and still be visible to the naked eye has to rank among the most bizarre ideas entertained by this world’s scientific community.

4.3 The Tychosium 3D simulator

As I timidly started my TYCHOS research back in 2013, I certainly had no ambition or pretence to build a digital planetarium that could remotely attain―let alone challenge―the accuracy of the currently available heliocentric simulators. My initial calculations were done with pen and paper and aided by simple graphic editing programs. However, as my research progressed over the years, I started entertaining the possibility of finding an IT wizard to help me bring to life the TYCHOS model by animating it on an interactive digital 3D platform. At the time of writing (January 2023), I am happy to say that the wondrous Tychosium 3D simulator has already surpassed my wildest dreams and expectations.

Fig. 4.3 Tracing planet movements in the Tychosium 3D simulator.

Fig. 4.3 Tracing planet movements in the Tychosium 3D simulator.

The Tychosium 3D simulator is a joint effort by yours truly and Patrik Holmqvist, a Swedish IT programmer I had the good fortune to meet in the summer of 2017. The Tychosium is still being developed and refined, yet we are both satisfied with its potential to become the most realistic and accurate digital simulator of the solar system ever devised. The principal feature of its superior nature lies in the fact that, once refined and completed, it should correctly show the conjunctions of the bodies of our solar system with the stars, without any geometric aberrations of parallax and perspective; i.e., without the anomalies and discrepancies that have vexed Copernican astronomers ever since the heliocentric model was introduced.

Before proceeding, I strongly encourage readers to open the Tychosium 3D simulator on their laptop computers and get familiar with its interactive functions. This is an essential requirement to fully visualize, assess and comprehend the workings of the TYCHOS model.

Go to the —>TYCHOSIUM 3D SIMULATOR ts.tychos.space

Fig. 4.4 The Tychosium 3D simulator and its control panel.

Fig. 4.4 The Tychosium 3D simulator and its control panel.

The Tychosium simulator is built upon the official astronomical tables compiled over the centuries by the world’s foremost astronomers. That is to say, all the orbital sizes, relative distances and empirically verifiable sidereal periods within the solar system have been rigorously respected. In the Tychosium, all the planets and moons move in uniformly circular orbits and at constant orbital speeds. This is in stark contrast with the elliptical orbits and variable speeds Kepler had to postulate to make the heliocentric model mathematically compatible with empirical observation. In all logic, I have therefore used the mean values of our planets’ estimated orbital velocities, disregarding their putative ‘maximum’ and ‘minimum’ values, as computed by Kepler.

Throughout the ages, astronomers have been in ceaseless pursuit of a configuration of the solar system consistent with the natural perception of uniformly circular orbits and constant orbital speeds. The TYCHOS provides an answer to their quest―one which can be challenged and tested in a state-of-the-art simulator.

Patrik and I hope you enjoy interacting with the Tychosium 3D simulator which―we dare say―is already the most realistic and true-to-nature simulator of the solar system available. If you are puzzled by the spirographic/trochoidal orbital patterns traced out in the Tychosium, keep in mind that all star systems observed in modern times display such patterns (see Chapter 2). From a purely probabilistic viewpoint, it would be unreasonable to think that our own solar system is the only one in the universe lacking trochoidal orbital patterns like the ones illustrated in Fig.4.5.

Fig. 4.5 Examples of observed patterns exhibited by the barycentric motions of 4 different exoplanet host stars.

Fig. 4.5 Examples of observed patterns exhibited by the barycentric motions of 4 different exoplanet host stars.

Using the TYCHOSIUM 3D simulator

A comprehensive users’ manual will be implemented in future upgrades of the Tychosium simulator. Meanwhile, here are some basic instructions and tips to get started:

-

- Click the “play” button > to start the TYCHOSIUM. You may then choose to speed up or slow down its motion with the “1 sec/step equals” function.

-

- Left-clicking (and holding) your mouse will let you toggle at will the 3-D orientation of our cosmos. The scroll wheel regulates the zoom level.

-

- Click on the “Trace settings” menu and choose any solar system body whose path you wish to be traced. You will then have to check the “Trace On/Off” box. Now, click “play” and enjoy the beautiful spirographic trajectories of our solar system’s various bodies, such as the charming 5-petalled flower pattern traced by Venus.

-

- To see the orientation of our zodiac’s 12 constellations, click on the “Stars & Helpers” menu and check the ‘Zodiac’ box.

-

- To see the celestial positions (ephemerides) of any of our solar system’s bodies, check the “Show positions” box in the “Controls” menu. You may also hover with your mouse over any celestial body to see their respective ephemeris data at any given time.

-

- By default, some of the bodies included in the simulator (e.g. Halley’s comet and asteroid Eros) are inactive. You can activate them in the “Planets & Orbits” menu.

-

- Currently, a dozen stars or so are included in the simulator. Their distances are all set by default to 200AU (in order to be readily visible as you open the Tychosium). You may however toggle their distances in the “Stars & Helpers” menu.

Fig. 4.6 The Sun’s path over 25344 years (the TYCHOS Great Year - or TGY).

Fig. 4.6 The Sun’s path over 25344 years (the TYCHOS Great Year - or TGY).

So far, the Tychosium has attained some quite remarkable concordance with all recorded planetary ephemerides, Mars oppositions, the transits of Venus and Mercury across the Sun’s disk, Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions, most other periodic interplanetary alignments and most solar and lunar eclipses. A few issues remain to be addressed (e.g., the secular rate of oscillation of our Moon’s declinations), yet we are confident that they will be resolved in due time. Fine-tuning a Solar System simulator is a tricky and time-consuming task, especially when you are a small team of two brains!

In the next chapter, we shall take a close look at Mars, which Kepler famously stated was the key to understanding the solar system. Sure enough, Mars is the ‘master key’ to unlock and unveil the true configuration and mechanics of our system. Ironically though, in spite of his obstinate attempts to reconcile the Martian motions with the heliocentric model, Kepler never found that all-important key, which is why he ultimately decided to forge it.