Chapter 15: Asteroid belts and Meteor showers

15.1 About the existence of the Main Asteroid Belt

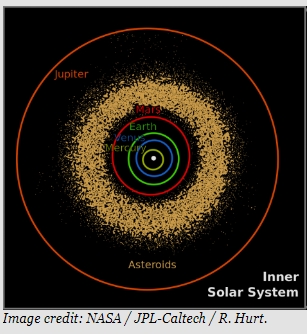

In this chapter we shall see how the existence of the Main Asteroid Belt, the Kuiper Belt and the periodic meteor showers lends support to the notion of the Sun and Mars being binary companions. The Main Asteroid Belt is located in the celestial region between Mars and Jupiter. Here’s how it is conventionally illustrated:

Fig. 15.1 The dense belt of dust / debris revolving between Mars and Jupiter image source: Wikimedia commons

Fig. 15.1 The dense belt of dust / debris revolving between Mars and Jupiter image source: Wikimedia commons

Over the centuries, many attempts have been made to explain why and how this belt of dust and debris came to be in the first place. One of the better-known theories posits that the asteroid belt consists of fragments of a large planet that occupied the Mars-Jupiter region many million years ago, before it was shattered by an internal explosion or a cometary impact. According to another theory, the hypothetical extra-Martian planet never actually formed:

“Why does our solar system have an Asteroid Belt? One theory that astronomers have is that 4.6 billion years ago, when our solar system was being formed, a tenth planet tried to form between Mars and Jupiter. However, Jupiter’s gravitational forces were too strong, so the material was unable to form a planet.” “Asteroid Belt”- Astronomical Society Astrophysics inreach at Cornell University (2006)

Clearly, these theories are mere vapid conjectures. What’s more, they are diametrically opposed: the first speculates that a planet did form in that region and then exploded. The second contends that no planet could ever have formed there due to the gravitational forces of Jupiter. Both fall short of describing any plausible cause or mechanism that would account for the Main Asteroid Belt’s formation, and the reason why it would have settled just outside of the orbit of Mars. Well, here’s the thing: asteroid belts are actually a component inherent in binary systems. They come into being as the wakes of dust and debris of the two companion bodies collide and get ejected in all directions, as illustrated in Figure 15.2.

Fig. 15.2 Mechanism of asteriod belt formation. (Source of animation: the Binary Research Institute.)

Fig. 15.2 Mechanism of asteriod belt formation. (Source of animation: the Binary Research Institute.)

Now, do we have any evidence that Mars keeps ejecting dust particles into its orbital wake? Yes, indeed: a quite recent astronomy article (March 2021) reported that the so-called ‘zodiacal light’ may be caused by Martian dust storms. This mysterious light has long been believed to be sunlight reflecting off dust particles moving in the plane of the solar system. Until the discovery in 2021, the particles were thought to derive from asteroids and comets.

“Why are these scientists confident that Mars’ dust is the source of the zodiacal light? Their statement explained: The researchers developed a computer model to predict the light reflected by the dust cloud, dispersed by gravitational interaction with Jupiter that scatters the dust into a thicker disk. The scattering depends only on two quantities: the dust inclination to the ecliptic and its orbital eccentricity. When the researchers plugged in the orbital elements of Mars, the distribution accurately predicted the tell-tale signature of the variation of zodiacal light near the ecliptic.” “Do Mars dust storms cause the mysterious zodiacal light?” - earthsky.org

As binary companions periodically cross paths along their intersecting orbits, fields of dust, particles and debris will be ejected and flung into a wider, circumbinary orbit. In the case of our Sun-Mars system, a structure like the Main Asteroid Belt is therefore expected to form just outside the orbit of Mars, in the celestial region between Mars and Jupiter. In fact, in later years, questions have been raised as to the apparent, yet unexpected, major role that ‘tiny’ Mars plays in the context of asteroids:

“Oddly enough, tiny Mars - with only 14 percent of Jupiter’s gravity - played a major role in explaining the Earth-crossing asteroids, although as Morbidelli acknowledges, “It may be astounding that Mars is so effective in stimulating chaos in the belt, because it is not massive. Did somebody say “chaos”? The Why Files is interested… Essentially “chaos” means that small perturbations - astronomese for “disturbances” - can cause large changes in orbits. Indeed, the improved simulation produced an inner asteroid belt that is almost entirely chaotic, Morbidelli says.” “Chaotic Asteroids” - whyfiles.org (1998)

Since asteroid belts consist of very small dust particles, they can be very difficult to detect. Nonetheless, more and more so-called ‘debris discs’ are being discovered and, sure enough, virtually all of them are being found around binary systems suspected of containing one or more planets. Most notably, circumbinary debris discs have been observed around systems such as Fomalhaut, Vega, Tau Ceti, Epsilon Eridani, Beta Pictoris and Copernicus (55 Cancri), all of which rank high on the lists of ‘exoplanet hunters’ (modern-day astronomers specializing in the detection of potentially habitable planets outside our solar system).

Fig. 15.3 “Debris disc” around binary system image source: “Fomalhaut” - Wikipedia

Fig. 15.3 “Debris disc” around binary system image source: “Fomalhaut” - Wikipedia

“The discovery of an asteroid belt-like band of debris around Vega makes the star similar to another observed star called Fomalhaut. The data are consistent with both stars having inner warm belts and outer cool belts separated by a gap. This architecture is similar to the asteroid and Kuiper belts in our solar system. The gap between the inner and outer debris belts for Vega and Fomalhaut also proportionally corresponds to the distance between our Sun’s asteroid and Kuiper belts. This distance works out to a ratio of about 1:10 with the outer belt 10 times farther away from its host star than the inner belt. As for the large gap between the two belts, it is likely there are several undetected planets, Jupiter-sized or smaller, creating a dust-free zone between the two belts.” “Telescopes find evidence for asteroid belt around Vega” by Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2013)

In other words, today we have empirical evidence of binary systems surrounded by both an inner and an outer asteroid belt, very much like the Main Asteroid Belt and the Kuiper Belt of our own system. Even the proportional distance (1:10) between the two closest and furthest asteroid belts observed in other binary star systems appear to be similar to that of our own solar system. How much more evidence is needed for astronomers to start entertaining the idea that we live in a binary system?

For what it’s worth, mainstream astronomers favor the hypothesis that water was brought to Earth by asteroids. No one really knows, but it is fascinating to read what is currently being hypothesized:

“FOLLOW THE WATER : More and more research suggests that asteroids delivered at least some of Earth’s water. Scientists can track the origin of Earth’s water by looking at the ratio of two isotopes of hydrogen, or versions of hydrogen with a different number of neutrons, that occur in nature. One is ordinary hydrogen, which has just a proton in the nucleus, and the other is deuterium, also known as ‘heavy’ hydrogen, which has a proton and a neutron. The ratio of deuterium to hydrogen in Earth’s oceans seems to closely match that of asteroids, which are often rich in water and other elements such as carbon nitrogen, rather than comets. (Whereas asteroids are small rocky bodies that orbit the sun, comets are icy bodies sometimes called dirty snowballs that release gas and dust and are thought to be leftovers from the solar system’s formation.) Scientists have also discovered opals in meteorites that originated among asteroids (they are likely pieces knocked off of asteroids). Since opals need water to form, this finding was another indication of water coming from space rocks. These two pieces of evidence would favor an asteroid origin.” “Where Did Earth’s Water Come From?” by Jesse Emspak (2016)

Ironically, the computer simulations rendered by exoplanet-hunting astrophysicists in order to assess the probability of the presence of water on planets in the ‘habitable zone’ of any given star system suggest that binary systems have a far higher probability (of several orders of magnitude) of containing planets harboring liquid water. In a single-star system, as that proposed by the Copernican model, there would be far less instability and fewer perturbations causing asteroids to be flung off course, making the delivery of ‘asteroid water’ to any given planet an unlikely event.

“Of course, this leaves the question of whether water transport via asteroids is a viable mechanism for supplying a single star planet system (like our own Earth) with liquid water. There are currently still several competing hypotheses as to how our planet obtained its water supply, but these sorts of simulations should shed light on the feasibility of water transport through impacting bodies.” — “Flinging Asteroids into the Habitable Zone” by Anson Lam (2015)

If these academic studies are anything to go by―and if Earth were part of a single-star system―it follows that the probability of water existing on our planet would be extremely low. Yet, about 71% of the Earth’s surface is drenched in water!

In conclusion, asteroid belts are now understood to be a distinctive feature of binary systems. Moreover, the existence of the Main Asteroid Belt just beyond the orbit of Mars appears to corroborate a fundamental premise of the TYCHOS model, as determined by Tycho Brahe over 400 years ago, namely that the orbit of Mars intersects the orbit of the Sun.

15.2 The meteor showers and the Sun-Mars orbits

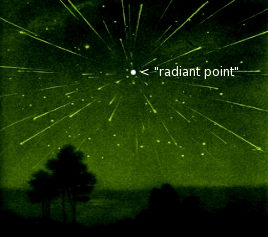

There’s probably no more fascinating celestial spectacle than the so-called shooting stars, as most of us have had the opportunity to witness. Amateur astronomers know where and when to look for even more spectacular events known as meteor showers. These events, which can last for a couple of days or up to several weeks, occur on a regular, annual basis in various parts of our skies and, quite reliably, in the same periods of the year. Most people will have heard of the largest known meteor showers, such as the Geminids, the Perseids, the Orionids and the Aquariids, all of which are named after the constellations or ‘radiant points’ from which they appear to originate.

Fig. 15.4 Radiant point of meteor shower

Fig. 15.4 Radiant point of meteor shower

But why do these meteor showers occur year after year around the same dates and appear to originate from almost the exact same celestial location? This is, in fact, an excellent question. Astronomers will tell you that these meteor showers occur every year as the Earth crosses the path of comets which leave debris behind. The problem with this theory is that none of our known comets return every single year. Halley’s comet, for instance, whose trail is believed to be responsible for two major annual meteor showers, returns only every 76 years or so. So we are actually meant to believe that the dust trails left by Halley’s comet somehow linger for decades on end along given tracts of space impacted annually by Earth, causing fairly similar meteor showers every single year.

I trust that anyone can sense the absurdity of the current justification for the annual recurrence of the various meteor showers. Surely, the fact that they occur each year over the same area of our skies must have a better and less fanciful explanation. What follows is a detailed, illustrated demonstration of how the TYCHOS can account for these recurring events.

Historically, meteor showers have been a cause of great perplexity among astronomers and cosmologists in their quest to discover what causes them and why they occur every year at virtually the same place in the sky. Let me outline the current understanding of the nature of meteor showers by reproducing a few excerpts from the Wikipedia:

“The actual nature of meteors was still debated during the 19th century. Meteors were conceived as an atmospheric phenomenon by many scientists (Alexander von Humboldt, Adolphe Quetelet, Julius Schmidt) until the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli ascertained the relation between meteors and comets in his work ‘Notes upon the astronomical theory of the falling stars’ (1867). A meteor shower is a celestial event in which a number of meteors are observed to radiate, or originate, from one point in the night sky. These meteors are caused by streams of cosmic debris called meteoroids entering Earth’s atmosphere at extremely high speeds on parallel trajectories. Most meteors are smaller than a grain of sand, so almost all of them disintegrate and never hit the Earth’s surface. A meteor shower is the result of an interaction between a planet, such as Earth, and streams of debris from a comet. Comets can produce debris by water vapor drag, as demonstrated by Fred Whipple in 1951, and by breakup.” “Meteor Shower” - Wikipedia

In other words, meteor showers are currently assumed to happen when Earth, hurtling around the Sun at 30 km/s, crosses streams of debris left over from comets which periodically visit our solar system. However, there are a number of problems with this theory:

-

Comets which enter our solar system rarely, if ever, stray right across (i.e., intersect with) Earth’s orbital plane (regardless of which solar system model is considered). Cometary orbits are almost invariably tilted in relation to Earth’s orbital plane and very few, if any, pass right through Earth’s celestial path. That is, most comets (which tend to be no larger than a few kilometers) pass either ‘above’ or ‘below’ the ecliptic and would thus be unlikely to leave any significant amount of debris for Earth to collide with.

-

Even if some comets intersected Earth’s orbit, it would take no longer than a few minutes at most for Earth to pass through the trail of debris, considering its alleged speed of 30 km/s. How then can large meteor showers last for several days or even weeks?

-

Comets have vastly different periods (e.g., 76 years for Halley’s comet and 3.3 years for Comet Encke). Indeed, the famous Perseid meteor shower is believed to be caused by the debris left behind by the Swift-Tuttle comet which has a period of no less than 133 years. How could this possibly explain the annual recurrence of the major meteor showers and their fairly regular intensities and durations? Is this cometary debris supposed to linger for years, decades or even centuries on end in the same area of the sky?

The working hypothesis of the TYCHOS model is quite simple: the major meteor showers are caused by the tiny particles continuously shed by the Sun and Mars along their orbital paths. As their slightly (mutually) inclined orbits occasionally intersect in both right ascension (RA) and declination (DECL), the dust trails of these binary companions will collide, sending ‘meteorites’ in all directions, both ‘upwards’ (towards the Main Asteroid Belt) and ‘downwards’ (towards the Earth). In any event, there appears to be ample evidence that several types of meteorites are of Martian origin:

“The proof of their Martian origin appears to be almost absolutely conclusive, based on the chemical signatures of gases (…).” “Martian meteorites” - Vanderbilt.edu

The following 4 animations depict how the meteor showers known as the Gemenids, the Perseids, the Orionids and the Aquariids would “play out” in the TYCHOS model. The animations were made with sequential screenshots from the Tychosium 3D simulator .

15.2.1 The Gemenid meteor shower

The famous Gemenid meteor shower recurs every year roughly between December 4th and December 17th, peaking on December 14th. The observed radiant point of this shower is located around 7h30min of RA. According to the Wikipedia, the average speed of the Gemenid meteors is 35 km/s. This means that, since the collision between the Sun’s and Mars’ orbital debris occurs at a distance of 1 AU (~150 million km), the Gemenid meteors take about 7 weeks to reach Earth’s atmosphere. Hence, we should expect the impact to take place in the last days of October and the shower to occur in mid-December. And, in fact…

Fig. 15.5 Genesis of the Gemenid meteor shower

Fig. 15.5 Genesis of the Gemenid meteor shower

15.2.2 The Perseid meteor shower

The well-known Perseid meteor shower recurs every year roughly between July 17th and August 24th, peaking on August 12th. The radiant point of this shower is located around 3 h of RA. According to the Wikipedia, the average speed of the Perseid meteors is 58 km/s. This means that, if the collision between the Sun’s and Mars’ orbital debris occurs at a distance of 1 AU, the Perseid meteors will reach Earth’s atmosphere after about 4 weeks. Hence, we should expect the impact to take place in the last days of July and the shower to become visible around mid-August. And, in fact…

Fig. 15.6 Genesis of the Perseid meteor shower.

Fig. 15.6 Genesis of the Perseid meteor shower.

15.2.3 The Orionid meteor shower

The Orionid meteor shower recurs every year roughly between October 2nd and November 7th, peaking on October 21st. The observed radiant point of this shower is located around 6h24min of RA. According to the Wikipedia, the average speed of the Orionid meteors is 67 km/s. This means that, if the impact between the Sun’s and Mars’ orbital wakes occurs at the distance of 1 AU, the Orionid meteors will employ about 3.7 weeks to reach Earth’s atmosphere. Hence, we should expect the impact to take place in early October and the shower to occur at the end of October. And, in fact…

Fig. 15.7 Genesis of the Orionid meteor shower

Fig. 15.7 Genesis of the Orionid meteor shower

15.2.4 The Delta Aquariid meteor shower

The beautiful Delta Aquariid meteor shower recurs every year roughly between July 12th and August 23rd, peaking on July 30th. The radiant point of this shower is located around 23h20min of RA. According to the Wikipedia, the average speed of the Delta Aquariid meteors is 41 km/s. This means that, if the impact between the Sun’s and Mars’ orbital wakes occurs at the distance of 1 AU, the Aquariid meteors will need about 6 weeks to reach Earth’s atmosphere. Hence, we should expect the impact to take place in mid-June and the shower to occur at the end of July. And, in fact…

Fig. 15.8 Genesis of the Delta Aquariid meteor shower.

Fig. 15.8 Genesis of the Delta Aquariid meteor shower.

15.2.5 Conclusion

You may now rightly wonder if those impact periods coincide with the actual intersections of the orbits of the Sun and Mars in both longitude and latitude. The answer to that most important question is ‘yes’. For instance, the annual impact zone of the Solar and Martian orbits responsible for the Perseid meteor shower is located at about 3h of RA and 15° of DECL, at a point in space where the orbits of the Sun and Mars intersect, as shown by the Tychosium 3D simulator.

Fig. 15.9

Fig. 15.9

In conclusion, I would submit that the TYCHOS model’s hypothesis for the occurrence of our major meteor showers holds water in terms of plausibility, logic and empirical probation―something that cannot be said for the current mainstream theories. Let us not forget that no comets are known to transit in our skies on a yearly basis and, thus, it makes little sense that week-long meteor showers would be caused by Earth annually scooting through tiny wakes of lingering cometary dust.

15.3 Are Mars meteors correlated with red rain?

As a speculative addendum to this chapter and a suggestion for further study, let us take a quick look at the possible connection between ‘Martian meteor dust’ and the controversial phenomenon known as ‘red rain’. Before moving on, keep in mind that―for what it’s worth―at least some meteorites have been shown to possess a chemical composition consistent with the elements believed to be found on Mars.

“It has for some time been accepted by the scientific community that a group of meteorites came from Mars. As such, they represent actual samples of the planet and have been analyzed on Earth by the best equipment available. In these meteorites, called SNCs, many important elements have been detected. Magnesium, Aluminium, Titanium, Iron, and Chromium are relatively common in them. In addition, lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, niobium, molybdenum, lanthanum, europium, tungsten, and gold have been found in trace amounts.” “Ore resources on Mars” - Wikipedia

Red rain (or ‘blood rain’ as it was called in Antiquity) is a hotly debated phenomenon which still lacks a satisfactory explanation, even though the Wikipedia boldly proclaims that “there is now a scientific consensus that the blood rain phenomenon is caused by aerial spores of green microalgae Trentepohlia annulata”. However, and as admitted by its very proponents, this theory lacks any rational explanation for the uptake (or ‘evaporation’) of these terrestrial algae into the clouds.

In recent decades, a flurry of controversy has surrounded the rare occurrence around the world of red rain downpours which can last for several weeks, much like the famous meteor showers treated in this chapter. For instance, a number of red rain showers took place between 2001 and 2012 in India and Sri Lanka, some of them following suspected and/or subsequently confirmed meteor airbust events. Samples of red rain were analyzed for their chemical composition by the Centre for Earth Science Studies (CESS):

“Some water samples were taken to the Centre for Earth Science Studies (CESS) in India, where they separated the suspended particles by filtration. Sediment (red particles plus debris) was collected and analysed by the CESS using a combination of ion-coupled plasma mass spectrometry, atomic absorption spectrometry and wet chemical methods. The major elements found were Carbon, Silicon, Calcium, Aluminium and Iron. The CESS analysis also showed significant amounts of heavy metals, including nickel (43 ppm), manganese (59 ppm), titanium (321 ppm), chromium (67ppm) and copper (55 ppm)”.

The chemical composition found in red rain appears to be fairly consistent with that found in Martian meteorites, but this is where my own musings on this particular subject will end. I will leave you with the abstract of a rather intriguing study published in 2003 by Godfrey Louis and Santhosh Kumar of the Mahatma Gandhi University:

“Red coloured rain occurred in many places of Kerala in India during July to September 2001 due to the mixing of huge quantity of microscopic red cells in the rainwater. Considering its correlation with a meteor airbust event, this phenomenon raised an extraordinary question whether the cells are extraterrestrial. Here we show how the observed features of the red rain phenomenon can be explained by considering the fragmentation and atmospheric disintegration of a fragile cometary body that presumably contains a dense collection of red cells. Slow settling of cells in the stratosphere explains the continuation of the phenomenon for two months. The red cells under study appear to be the resting spores of an extremophilic microorganism. Possible presence of these cells in the interstellar clouds is speculated from its similarity in UV absorption with the 217.5 nm UV extinction feature of interstellar clouds.” Cometary panspermia explains the red rain of Kerala - by Godfrey Louis & A. Santhosh Kumar (2003

Then there is of course Prof. Chandra Wickramasinghe’s thought-provoking Panspermia Theory, but disquisitions about how life arose on this planet are, as you may appreciate, well beyond the scope of this book. In my humble view, we ought to focus our efforts on getting the configuration of the solar system right before engaging in ambitious Promethean quests to unravel the origins of terrestrial life and the inception of the universe.