Chapter 23: Are the stars much closer than believed?

23.1 What is a ‘light year’?

The most indigestible aspect of the heliocentric theory is undoubtedly its implications for the remoteness and sizes of the stars. The idea that perfectly visible stars would be located several thousand light years away is, on the face of it, outlandish. Let’s pause for a moment to consider what exactly a light year (LY) is and how it translates into astronomical units (AU) and kilometers.

• 1 AU (average Earth-Sun distance) = 149 597 870.7 km (~149.6 Mkm)

• 1 LY = 63241.1 AU = 9 460 730 472 580.8 km (~9.46 trillion kilometers)

Since the advent of heliocentrism, the apparent angular diameter of the stars as perceived from Earth by the human eye has been one of the most controversial issues of astronomy. The new theory implied that the stars were hugely more distant than previously thought, making it imperative to find some justification for the apparent size of the stars. In fact, the stars, especially the largest or closest stars of first magnitude, appear to be far too big to support the Copernican notion of formidable remoteness. Common sense tells us visible stars are not all grotesquely large and remote, but can we back this natural perception up with rational arguments? The answer to this question is firmly in the affirmative, and the TYCHOS model can help us formulate it.

23.2 The ‘42633 reduction factor’

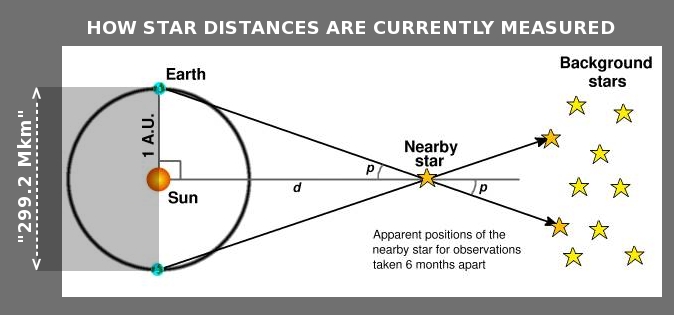

Copernican astronomers have always measured and computed star distances under the assumption that Earth moves around the Sun in an orbit 299 200 000 km wide. To do so, they ‘take a picture’ of a nearby star on two dates six months apart (say, on 21 June and 21 December). Comparing the two pictures will show how much the observed star appears displaced in relation to the ‘fixed stars’ (i.e., the far more distant background stars), and by using simple trigonometry the distance between the Earth and the star can be estimated.

Fig. 23.1 The current principle of how star distances are measured.

Fig. 23.1 The current principle of how star distances are measured.

Now, if Earth does not revolve around the Sun in a 300 Mkm wide orbit, the current basis for calculating star distances is completely wrong. As we have seen, in the TYCHOS model, Earth only moves by 14036 km every year, or by 7018 km every 6 months. Based on the 7018 km figure, the currently accepted star distances should be reduced by a factor of ~42633 (299 200 000 / 7018). This will be our TYCHOS reduction factor for all the stellar distances listed in the official star catalogues.

Applying the TYCHOS reduction factor, 1 ‘official LY’ in reality corresponds to ~1.5 AU:

• The TYCHOS reduction factor = ∼42633

• 1 ‘TYCHOS LY’ = 63241.1 AU / 42633 ≈ 1.4834 AU

Note that the ‘TYCHOS LY’ is a unit of distance, with no implication for the speed of light. But talk is cheap, so let us test the TYCHOS reduction factor in a couple of real-life scenarios, starting with the well-known star Proxima Centauri (our nearmost star). Proxima is said to be about 4.25 LY away. In the TYCHOS model, this would translate into 6.3 AU (4.25 x 1.4834).

This is rather interesting. At a distance of 6.3 AU, Proxima Centauri would be roughly halfway between Jupiter (4.2 AU) and Saturn (8.5 AU) if it were not for the fact that it is not located in the same plane as the Solar System, but some 62° ‘below’ it. Also, consider that Proxima is reckoned to be a ‘red dwarf’; as we saw in Chapter 2, this dim type of star is by far the most common in the universe..

Undoubtedly, Tycho Brahe would be most satisfied with this finding, since his primary objection to the Copernican model was that the stars would have to be absurdly large and distant and that there would be an immense void between Saturn and our nearmost stars. In fact, Brahe’s expert opinion was that the stars were “located just beyond Saturn and of reasonable size”.

“It was one of Tycho Brahe’s principal objections to Copernican heliocentrism that in order for it to be compatible with the lack of observable stellar parallax, there would have to be an enormous and unlikely void between the orbit of Saturn (then the most distant known planet) and the eighth sphere (the fixed stars).” “Parallax” - on Wikipedia

Fig. 23.2

Fig. 23.2

We shall now use Proxima Centauri as a ‘test bed’ to explore another controversial issue, namely that of the perceived telescopic size of stellar disks. As all astronomers will know, the perceived angular diameters of the stars, as viewed telescopically, are commonly believed to be spurious due to assorted diffraction phenomena which would cause the stars to appear far larger to the naked eye than they are in actuality. More on that further on.

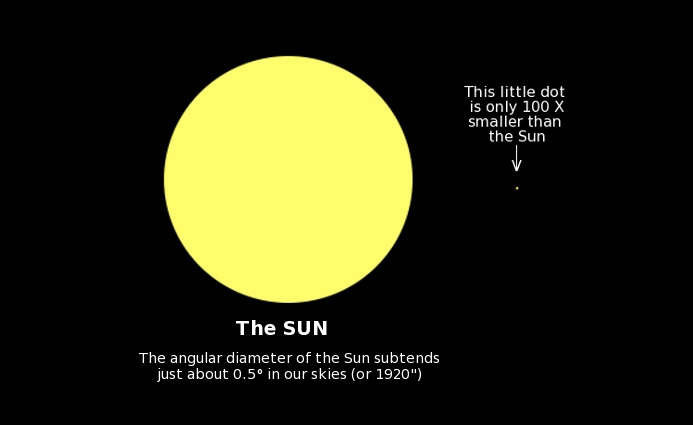

Proxima’s officially estimated ‘true’ angular diameter is 0.001 arcseconds, though it certainly appears much larger in our telescopes. Since the Sun’s observed angular diameter is 1920 arcseconds, Proxima’s ‘actual’ angular diameter is thus reckoned to be 1 920 000 times smaller than the Sun’s. That’s almost 2 million times smaller! To put this into perspective, Figure 23.3 shows how an object a hundred times smaller than the Sun would look like in the night sky. Now, if the tiny dot in the figure was not just a hundred times but 2 million times smaller, I think we can all agree it would be invisible. Let that sink in.

Fig. 23.3 What a dot only 100 x smaller than the Sun would look like.

Fig. 23.3 What a dot only 100 x smaller than the Sun would look like.

Proxima’s actual diameter is estimated by mainstream astronomers to be 1/7 that of our Sun. If the star were really 40 trillion km away (4.25 x 9 460 730 472 580.8 km), it would be 268775 times more remote than our Sun. According to this reasoning, the ‘true’ angular diameter would be 0.001″, an absurdly small value, whichever way you look at it.

• Angle subtended by Proxima if it were as big as the Sun = 1920” / 268775 ≈ 0.007”

• Officially claimed ‘true’ angular diameter of Proxima = 0.007” / 7 ≈ 0.001”

Now, is Proxima perhaps an exceptionally bright star? Well no, not according to officialdom. Here is what the Wikipedia has to say about Proxima’s luminosity:

“(Proxima’s) total luminosity over all wavelengths is 0.17% that of the Sun, although when observed in the wavelengths of visible light the eye is most sensitive to, it is only 0.0056% as luminous as the Sun.” “Proxima Centauri” - Wikipedia

In other words, the official data are telling us that Proxima, our very nearmost star…

• is about 7 times smaller than our Sun.

• is located 268775 times farther away than our Sun.

• has a far lower luminosity than our Sun (0.17% or less).

• has a ‘true’ angular diameter almost two million times smaller than our Sun

In light of these official claims, it is hard to fathom how Proxima Centauri can possibly be observed with a run-of-the-mill amateur telescope. On the other hand, assuming the TYCHOS reduction factor for star distances is correct, Proxima’s true angular diameter would amount to a more reasonable 42.633 arcseconds (42633″ x 0.001 = 42.633″), making its angular diameter only 45 times smaller than the Sun’s mean angular diameter of 1920″ (1920″ / 42.633″ ≈ 45). Note that 42 arcseconds is well below the angular resolution of the human eye (60″), so applying the TYCHOS reduction factor does not imply Proxima would be visible to the unaided eye from a distance of 6.3 AU. Yet, if it were placed next to our Sun, at a distance of only 1 AU, it would indeed be seen to be about 7 times smaller than the Sun (45 / 6.3 ≈ 7.1).

Let us now see how this same line of reasoning works out when applied to Sirius, the brightest and visually largest star in the firmament..

“At just 8.6 light years away, Sirius is the seventh closest star to Earth.” “What is the brightest star in our skies?” - Sky & Telescope

If we apply our 42633 reduction factor (1 ‘TYCHOS LY’ = 1.4834 AU) to the Earth-Sirius distance, we get about 12.76 AU (8.6 × 1.4834 ≈ 12.76). Offcially, the ‘true’ angular diameter of Sirius is taken to be a mere 0.005936”, again an incredibly small value. This would mean that the ‘actual’ size of the disk of light we call Sirius is 323450 times smaller than that of the Sun (1920” / 0.00593600 = 323450). Now, Sirius is officially estimated to be 1.7 times larger than the Sun; so let us see what the Earth-Sirius distance would be under the TYCHOS model’s proposed 42633 reduction factor. First we divide 323450 by 42633 to obtain the hypothetical Earth-Sirius distance if Sirius were the same size as the Sun, then we multiply the result by 1.7, assuming the officially estimated ratio between the physical diameters of the Sun and Sirius (1:1.7) is correct.

• Distance to Sirius if it were the same size as the Sun = 323450 / 42633 ≈ 7.5868 AU

• Distance to Sirius assuming it is 1.7 times larger than the Sun = 7.5868 × 1.7 ≈ 12.89 AU

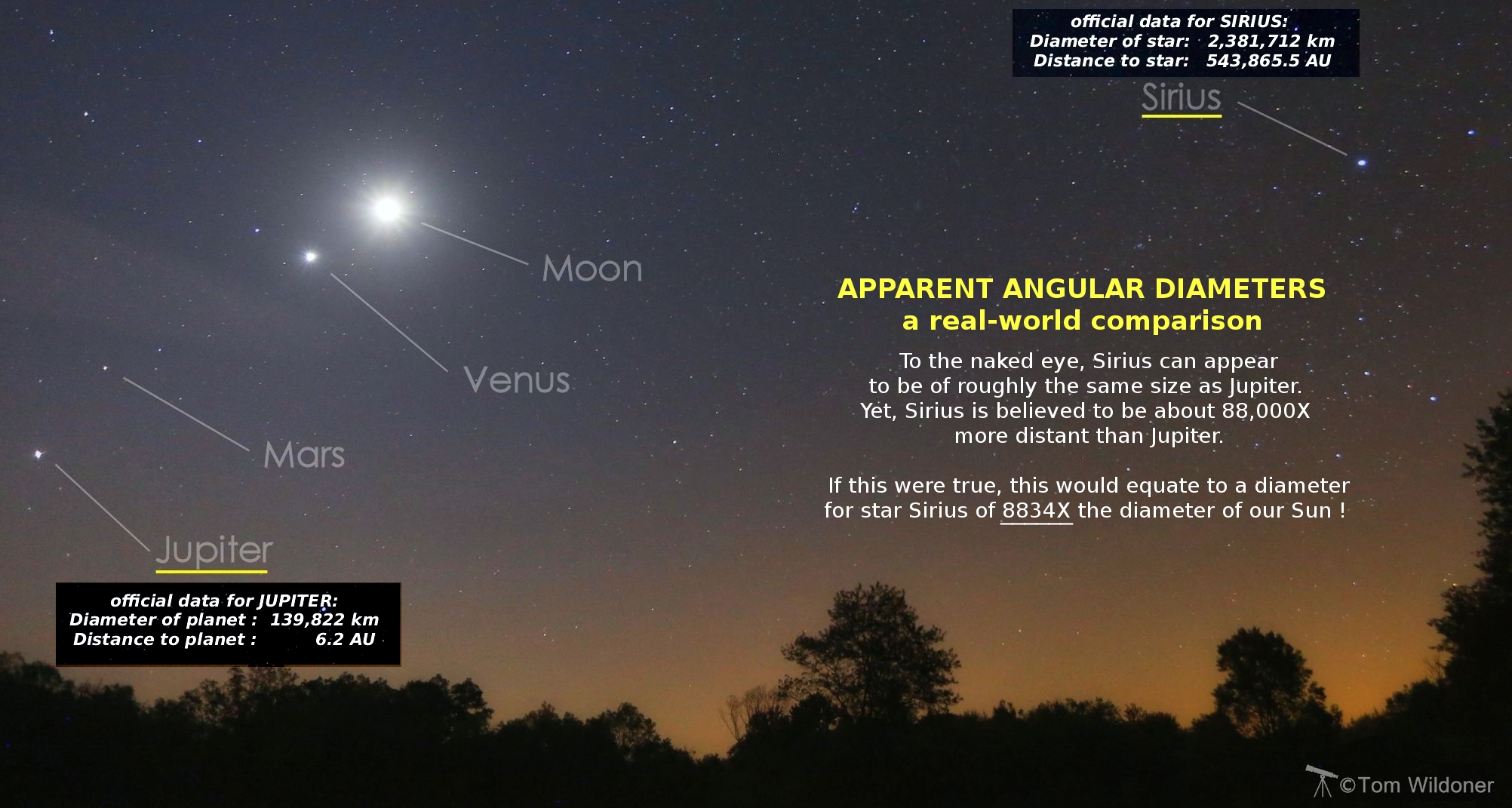

Again, Tycho Brahe would likely have been satisfied with the notion that the brightest star in our skies might be located some 3.4 AU farther away than Saturn, itself located some 9.5 AU away (while being a considerably fainter object in the sky than Sirius). So could Sirius be located at about 12.8 AU, yet still be 1.7 times larger than the Sun? It is not possible to say with certainty at this point, not without further study. However, take a minute or two to consider the heliocentrists’ absurd claim that Sirius is located a whopping 550000 times farther away than the Sun, or 88000 times farther away than Jupiter. A photograph of the night sky will help illustrate the issue at hand. Note the fairly similar sizes of Sirius and Jupiter to the naked eye:

Fig. 23.4 A visual comparison between the observed sizes of Jupiter and Sirius. Keep in mind that Saturn (unfortunately absent in this photograph) is about 13 times fainter than Jupiter. Sirius thus outshines Saturn by a considerable amount. Photograph by Tom Wildoner - October 8, 2015

Fig. 23.4 A visual comparison between the observed sizes of Jupiter and Sirius. Keep in mind that Saturn (unfortunately absent in this photograph) is about 13 times fainter than Jupiter. Sirius thus outshines Saturn by a considerable amount. Photograph by Tom Wildoner - October 8, 2015

The Sun subtends about 0.53° (or 1920 arcseconds) in the sky, roughly the same as the Moon. Now, take a good look at the photograph in Figure 23.4 and compare the sizes of the Moon and Sirius. Does Sirius appear to be several hundred thousand times smaller than the Moon?

Astronomers have been debating the thorny subject of the observed star sizes for centuries. Ironically, it was that epochal technological advancement, the telescope, that provided the Copernicans with some ‘optical justification’ (another excuse of the ‘stellar aberration’ type) for this seemingly intractable issue, courtesy of Astronomer Royal George Airy—yes, the very same fellow who were to falsify James Bradley’s nebulous ‘stellar aberration’ theory. Mind you, the so-called ‘Airy disk’ theory is hardly any less of an obscure and contentious affair. Here it is described by the Wikipedia:

“Airy Disk : The resolution of optical devices is limited by diffraction. So even the most perfect lens can’t quite generate a point image at its focus, but instead there is a bright central pattern now called the Airy disk, surrounded by concentric rings comprising an Airy pattern. The size of the Airy disk depends on the light wavelength and the size of the aperture. John Herschel had previously described the phenomenon, but Airy was the first to explain it theoretically. This was a key argument in refuting one of the last remaining arguments for absolute geocentrism: the giant star argument. Tycho Brahe and Giovanni Battista Riccioli pointed out that the lack of stellar parallax detectable at the time entailed that stars were a huge distance away. But the naked eye and the early telescopes with small apertures seemed to show that stars were disks of a certain size. This would imply that the stars were many times larger than our sun (they were not aware of supergiant or hypergiant stars, but some were calculated to be even larger than the size of the whole universe estimated at the time). However, the disk appearances of the stars were spurious: they were not actually seeing stellar images, but Airy disks. With modern telescopes, even with those having the largest magnification, the images of almost all stars correctly appear as mere points of light.” “George Airy” - Wikipedia

In short, Airy proclaimed that we cannot trust our eyes, or telescopes, when it comes to gauging the angular diameters of the stars, since “the resolution of optical devices is limited by diffraction”. Moreover, naked-eye assessments of star sizes would be entirely spurious and utterly useless because starlight would be greatly inflated by ‘atmospheric diffraction’ as it traverses Earth’s atmosphere. However, there is an obvious problem with this theory: why isn’t the light emanating from the Sun and our planets similarly affected? Light is light regardless of how remote the source is and should suffer the same distortion, if any, upon traversing our atmosphere. The notion that atmospheric diffraction would hugely inflate the apparent sizes of the stars but not those of our planets is one of the most bizarre axioms of heliocentrism.

Tycho Brahe’s estimate of the angular diameter of Vega—a so-called ‘first-magnitude’ star—was 120 arcseconds, which is 16 times smaller than the angular diameter subtended by the Sun (1920 arcseconds). Now, before you start scoffing at Brahe’s ‘generous’ estimate of the angular size of Vega, consider the following easily verifiable facts: if you hold an old LP vinyl record at arm’s length in front of the Sun, the Sun’s disc will just about fit into the 7-mm hole in the middle. Ergo, the Sun’s angular diameter subtends about 7 millimeters at arm’s length. In Tycho Brahe’s expert judgment, Vega’s angular diameter is only 16 times smaller than that of our Sun. Figure 23.5 may help determine how realistic his reckoning was:

Fig. 23.5

Fig. 23.5

The tiny dot in Figure 23.5 does not look too different from what we see in reality. In light of this, Tycho Brahe’s contention that ‘first magnitude’ stars like Vega are only about 16 times smaller than the Sun seems quite reasonable. Nevertheless, much like Groucho Marx, mainstream astronomers insist that we reject the evidence of our own eyes and that the angular diameter of Vega is in reality 622000 times smaller than the Sun’s.

Vega is currently believed to be 25 Copernican LY away, i.e. over 1.5 million times more distant than our Sun. Yet, Vega’s physical diameter is estimated to be only about 2.3 times larger than the solar diameter. Now, if we take the Sun in Figure 23.5 and enlarge it 2.3 times, then scale it down 1.5 million times, it would not be visible from Earth with any sort of telescope, let alone to the naked eye.

Vega’s intrinsic luminosity (or ‘wattage’, if you will) is officially estimated to be 37 times stronger than our Sun’s. This is most interesting because Vega—considered by astronomers to be “the next most important star in the sky after the Sun”—is probably the most studied of all stars and has been used as a baseline for calibrating the photometric brightness scale. Now, according to the TYCHOS model, Vega is about 37 times more distant than the Sun. It may thus be reasonably inferred that the luminosities of the Sun and Vega are, in actuality, alike: what astronomers interpret as a 1:37 luminosity ratio between the two stars may only be due to their different remoteness from the Earth. In any event, the problems posed by the alleged ginormous stellar distances implied by the Copernican model should now have become painfully clear.

Tycho Brahe’s main objection to the Copernican model was that the stars could not be so formidably distant unless they were, without exception, hugely larger than our Sun. Brahe reckoned instead that the respective diameters of the visible stars were more homogeneous, i.e. only somewhat larger or smaller than that of our Sun, as opposed to dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of times larger. One must admit that, from a purely statistical viewpoint, this makes perfect sense, for why would there be so many ‘giant’ and ‘supergiant’ stars in our galactic neighbourhood? To be sure, the Wikipedia tells us that “giant stars have radii up to a few hundred times the Sun and luminosities between 10 and a few thousand times that of the Sun, whereas the radii of supergiant stars can be in excess of 1,000 solar radii [with] luminosities from about 1,000 to over a million times the Sun.”

Now, if the TYCHOS reduction factor is correct, does that mean Vega is 42633 times smaller than the official estimate of 2.3 times the size of the Sun? No, Vega may actually still be about 2.3 times larger than the Sun. Here is why:

• Vega’s angular diameter according to Tycho Brahe = 120” (1/16 of the Sun)

• Vega’s angular diameter according to Copernican astronomers = 0.0029”

• Apparent size ratio = 120 / 0.0029 ≈ 41380 (i.e., fairly close to the 42633 TYCHOS reduction factor)

⇒ Remember: 1 Copernican LY = 63241.1 AU, and 1 ‘TYCHOS LY’ = 1.4834 AU

• Earth-Vega distance in the Copernican model = 25.04 LY

• Earth-Vega distance in the TYCHOS model = 25.04 × 1.4834 = 37.144 AU

• Size ratio of Vega relative to the Sun = 37.144 / 16 ≈ 2.32

So perhaps Tycho Brahe was right all along about star sizes and distances. In any event, his estimate for Vega’s angular diameter would seem to agree with the TYCHOS model’s proposed reduction factor (42633), but keep in mind that even if the stars are 42633 times closer than believed by heliocentrists, it doesn’t necessarily follow that their actual diameters are 42633 times smaller than current estimates. Today, Brahe’s reckonings of the angular diameters of first magnitude stars (2 arcminutes) would seem wildly exaggerated. Yet, in his time, a number of eminent astronomers estimated them to be even larger than that. Kepler, for instance, estimated the angular diameter of Sirius to be 4 arcminutes (or 240″):

“Magini took the stars of the first mag. to be 10’ in diameter; Kepler made the diameter of Sirius 4’ (Opera, ii. p. 676); the Persian author of the Ayeen Akbery put the diameter of stars of the first mag. = 7’ (Delambre, Moyen Age, p. 238), so that Tycho’s estimates were more reasonable than any of these.” “Further work on the star of 1572”

As we have seen, the modern estimate for Sirius is 0.005936″, or about twice the angular diameter of Vega (0.0029″). This is most interesting since it would mean that Brahe (whose known estimate for Vega was 120″) and Kepler (whose known estimate for Sirius was 240″) were actually in excellent agreement with regard to the observed angular diameter of the stars.

23.3 How can we see so many stars with our naked eyes?

An inescapable question for the world’s astronomers: how can so many stars, reputedly hundreds or thousands of light years away, be visible to the unaided eye? How large would they have to be?

“In the absence of any observed stellar parallax, Tycho scoffed for example at the absurdity of the distance and the sizes of the fixed stars that the Copernican system required: Then the stars of the third magnitude which are one minute in diameter will necessarily be equal to the entire annual orb (of the earth), that is, they would comprise in their diameter 2284 semidiameters of the earth. They will be distant by about 7850000 of the same semidiameters. What will we say of the stars of first magnitude, of which some reach two, some almost three minutes of visible diameter? And what if, in addition, the eighth sphere were removed higher, so that the annual motion of the earth vanished entirely (and was no longer perceptible) from there? Deduce these things geometrically if you like, and you will see how many absurdities (not to mention others) accompany this assumption of the motion of the earth by inference.” “Tycho Brahe’s Critique of Copernicus and the Copernican System” - by Ann Blair (1990)

Let us consider the distance currently claimed for one of our brighter stars, Deneb (also called Alpha Cygni). Deneb is said to be about 200 times larger than our Sun, but we are also told it is a whopping 2600 LY (~164 426 800 AU, or 24 598 249 280 000 000 km) away from our eyes. That’s over 164 million times more remote than the Sun! And yet:

“Deneb is one of the brightest stars we can see with the naked eye.” “Night Sky: Look Northeast For Deneb” - by Steven Glazier

“A blue-white supergiant, Deneb is also one of the most luminous stars. However, its exact distance (and hence luminosity) has been difficult to calculate; it is estimated to be somewhere between 55,000 and 196,000 times as luminous as the Sun.” “Deneb” - Wikipedia

Pardon me? “Between 55000 and 196000 times as luminous as the Sun”? With such a large error margin, it sounds more like guesswork. Besides, these formidable luminosity levels may very well be a way of justifying the untinkable stellar distances that the Copernican model requires for its survival. What sort of otherworldly physics would cause a star to shine 196000 times brighter than our Sun? Didn’t Sir Isaac tell us that the laws of physics are the same throughout the universe?

“One 2008 calculation using the Hipparcos data (gathered by ESA’s Hipparcos satellite) puts the most likely distance (to Deneb) at 1550 light-years, with an uncertainty of only around 10%.” “Deneb” - Wikipedia

Some modern planetariums have Deneb at a distance of 3227 light years, i.e. over twice the distance estimated by ESA. Do the stellar distance estimates of mainstream astronomers ever agree with each other? Is Deneb 1550 or 2600 or 3227 light years away? Evidently, no one seems to know with any reasonable degree of precision. I, for one, grew up with the notion that the science of astronomy was far more exacting than this. Virtually none of these claimed star distances and luminosities add up. They are all, as TV celebrity Carl Sagan liked to say, “extraordinary claims that require extraordinary evidence”. It should thus come as no surprise that, as we shall see further on, several independent astronomers have in later years vigorously questioned NASA and ESA (the European Space Agency) over the star distances published in their official catalogues.

In any event, should the stars be much closer than currently believed, this would certainly help explain why we can see very distant stars like Deneb with the naked eye and why ‘first magnitude’ stars like Sirius and Vega can appear to be of roughly the same size as Jupiter. To be sure, much more study is needed in the field of optical astronomy, a branch of human knowledge rife with controversy still today. The long-debated question of the perceived telescopic star disk sizes and how they are affected by assorted optical phenomena is far from being a settled matter. The same goes for the use of redshift and blueshift Doppler effects to determine whether stars are receding from or approaching our Solar System. But more on that in Chapter 26.

23.4 About our relative speed in relation to the stars

The velocity value of 19.4 km/s keeps popping up all over astronomy literature. As shown by the quotes below, there appears to be some sort of consensus regarding this velocity value, although its actual meaning is rather nebulous. What is this speed measured against? It appears this value is meant to represent the ‘perceived average relative speed’ of our Solar System in relation to the stars, as computed within the Copernican framework, with its grossly inflated Earth-star distances.

“…The solar system itself has a velocity of 20km/s with respect to the local standard of rest of nearby stars…” “Cross-Calibration of Far UV Spectra of Solar System Objects and the Heliosphere” by Quémerais, Snow and Bonnet

“The average radial velocity of the stars is of the order of 20 km per second”. “The Motion of the Stars” by J. S. Plaskett (1928)

Fig. 23.6 Extract from “The Motion of the Stars”, by J. S. Plaskett (April 1928).

Fig. 23.6 Extract from “The Motion of the Stars”, by J. S. Plaskett (April 1928).

“The Sun’s peculiar velocity is 20 km/s at an angle of about 45 degrees from the galactic centre towards the constellation Hercules.” “Spiral Galaxies” by Dmitri Pogosian (2018)

“The Sun is moving towards Lambda Herculis at 20km/s. This speed is in a frame of rest if the other stars were all standing still.” “What is the speed of the Solar System?” by Scherrer, Tai and Hoeksema (2017)

“The speed of the Sun towards the solar apex is about 20 km/s. This speed is not to be confused with the orbital speed of the Sun around the Galactic center, which is about 220 km/s [or 800.000 km/h] and is included in the movement of the Local Standard of Rest.” “Solar apex” - Wikipedia

The Paris Observatory provides the more exacting figure of 19.4 km/s, or a displacement of “about 4 AU/year”:

“Solar apex: The point on the celestial sphere toward which the Sun is apparently moving relative to the Local Standard of Rest. Its position, in the constellation Hercules is approximately R.A. 18h, Dec. +30°, close to the star Vega. The velocity of this motion is estimated to be about 19.4 km/sec (or about 4 AU/year). As a result of this motion, stars seem to be converging toward a point in the opposite direction, the solar antapex.”

“Antapex: The direction in the sky away from which the Sun seems to be moving (at a speed of 19.4 km/s) relative to general field stars in the Galaxy.” “An Etymological Dictionary of Astronomy and Astrophysics” / Paris Observatory by M. Heydari-Malayeri

In the interest of accuracy, we should probably use this 19.4 km/s value as it appears to be the most widely accepted estimate today. This velocity is essentially described as representing the motion of the Solar System relative to the stars. Hence, if the stars are in fact much closer to us than currently believed, their perceived (heliocentric) velocity should be divided by our 42633 reduction factor.

• 19.4 km/s × 3600 = 69840 km/h, and 69840 km/h / 42633 ≈ 1.638 km/h

⇒ Orbital velocity of the Earth in the TYCHOS model = 1.601169 km/h

Next, let us apply our 42633 reduction factor to the “4 AU/year” displacement estimate of the Paris Observatory:

• 4 AU ≈ 598 400 000 km, and 598 400 000 km / 42633 ≈ 14036 km

⇒ Annual displacement of the Earth along its PVP orbit = 14036 km

In conclusion, the general velocity perceived to exist between the stars and our Solar System (ca. 19.4 km/s) would seem to support both of the TYCHOS model’s “boldest” - yet most fundamental assertions:

• Earth moves at the very tranquil speed of 1.6 km/h

• The stars are about 42633 times closer than currently estimated

23.5 About the solar apex and the solar antapex

Untold efforts have been made to determine the spatial progression and direction of the Sun in relation to the surrounding stars. Astronomers have coined the term ‘solar antapex’ to indicate the point in the sky from which the Sun appears to be receding, and the term ‘solar apex’ to indicate the point in the sky towards which the Sun appears to be moving. It has now finally been determined that the Sun is receding from the celestial ‘longitude point’ of 6h28m RA (roughly in the direction of the Sirius system) and approaching the celestial ‘longitude point’ of 18h28m RA (roughly in the direction of Vega). Source: “Solar Apex” - Wikiwand

This turns out to be in most excellent accordance with the TYCHOS model. The below screenshots from the Tychosium 3D simulator show that the Sun will indeed be moving in such manner in the next 12672 years (½ TGY). In this respect, the TYCHOS model is fully consistent with the observed and computed secular progression and direction of the Sun as it proceeds away from the solar antapex and towards the solar apex.

Fig. 23.7 Screenshots from the Tychosium 3D simulator. The TYCHOS model agrees with the observed direction of the Sun’s secular motion, from its antapex (RA: 6h28m) to its apex (RA: 18h28m).

Fig. 23.7 Screenshots from the Tychosium 3D simulator. The TYCHOS model agrees with the observed direction of the Sun’s secular motion, from its antapex (RA: 6h28m) to its apex (RA: 18h28m).

In the next chapter, we shall see how Earth’s purported translational velocity of 107226 km/h has never been experimentally verified nor confirmed. This is a hard fact which no earnest astronomer can deny, yet relativists will unfailingly roll their eyes and tell you that “Einstein has long explained why the Earth’s translational velocity is impossible to verify!”