Chapter 3: About our Sun-Mars binary system

3.1 The Sun, Mars and the Earth, and their moons

Fig. 3.1 A screenshot from the Tychosium 3D simulator (www.ts.tychos.space)

Fig. 3.1 A screenshot from the Tychosium 3D simulator (www.ts.tychos.space)

The first objection people make to the idea that Mars is the Sun’s binary companion is usually something like: “Nonsense! Mars is a planet, not a star!” Yes, today’s astronomers do indeed refer to Mars as a ‘planet’, even though, as we shall see, Kepler himself called Mars a ‘star’ (Stellae Martis, in Latin). In any case, the distinction between a planet and a star is not as clear-cut as it may seem. Many ‘stars’ don’t even appear to shine with their own light: for instance, countless red and brown dwarfs are so dim that they remain completely invisible even to our largest telescopes. In fact, red dwarfs are the most common ‘stars’ in our skies:

“Red dwarfs are by far the most common type of star in the Milky Way, at least in the neighborhood of the Sun, but because of their low luminosity, individual red dwarfs cannot be easily observed. From Earth, not one star that fits the stricter definitions of a red dwarf is visible to the naked eye.” Red dwarf (Wikipedia)

As any amateur astronomer will know, Mars is a solid reddish-orange sphere reflecting the light of the Sun, but to the naked eye it shines almost like a star. Incidentally, it is worth noting that Mars is the only reddish-orange body in our Solar System.

Fig. 3.2 Similarities between Mars and brown dwarf.

Fig. 3.2 Similarities between Mars and brown dwarf.

You may now ask: “How do we know about the existence of dwarf stars which are invisible even to our largest telescopes?” We know this thanks to sophisticated instruments called spectroscopes which are routinely used to detect the invisible companions of larger stars. Cecil G. Dolmage has succinctly described the basic workings of the spectroscope thus:

“There are certain stars which always appear single even in the largest telescopes, but when the spectroscope is directed to them a spectrum with two sets of lines is seen. Such stars must, therefore, be double. Further, if the shiftings of the lines, in a spectrum like this, tell us that the component stars are making small movements to and from us which go on continuously, we are therefore justified in concluding that these are the orbital revolutions of a binary system greatly compressed by distance. Such connected pairs of stars, since they cannot be seen separately by means of any telescope, no matter how large, are known as “spectroscopic binaries.”

However, it should be noted that even spectroscopes will fail to determine whether star companions detected in such manner shine with their own light:

“In observations of spectroscopic binaries we do not always get a double spectrum. Indeed, if one of the components be below a certain magnitude, its spectrum will not appear at all; and so we are left in the strange uncertainty as to whether this component is merely faint or actually dark. It is, however, from the shiftings of the lines in the spectrum of the other component that we see that an orbital movement is going on, and are thus enabled to conclude that two bodies are here connected into a system, although one of these bodies resolutely refuses directly to reveal itself even to the all-conquering spectroscope.” -“Astronomy of To-day - A Popular Introduction in Non-Technical Language” - by Cecil G. Dolmage (1908)

Today, we know that the vast majority of our visible stars have one or more faint or invisible companions, and astronomers are discovering new binary systems at an ever-increasing rate. Surely, this has to be the most significant, paradigm-changing astronomical epiphany of our modern age! One can only wonder why such persistent findings haven’t yet sparked a major debate questioning the ‘implicit exceptionalism’ of the Copernican heliocentric theory—what with its companionless ‘non-binary star’ (the Sun) and its gigantic 240-million-year orbit.

Having said that, there does appear to be a growing awareness within select astronomy circles of the awkwardness of the notion of a solitary Sun. Here is, for instance, a short excerpt from a recent article published on the Science Alert website in November 2018:

“Our Sun is a solitary star, all on its ownsome, which makes it something of an oddball. But there’s evidence to suggest that it did have a binary twin, once upon a time. Recent research suggests that most, if not all, stars are born with a binary twin. (We already knew the Solar System is a total weirdo. The placement of the planets appears out of whack compared to other systems, and it’s missing the most common planet in the galaxy, the super-Earth.)” Science Alert (Nov 20, 2018)

Another article published in June 2017 on the PhysOrg website carries this most interesting title: “New evidence that all stars are born in pairs”.

“Astronomers have speculated about the origins of binary and multiple star systems for hundreds of years, and in recent years have created computer simulations of collapsing masses of gas to understand how they condense under gravity into stars. They have also simulated the interaction of many young stars recently freed from their gas clouds. Several years ago, one such computer simulation by Pavel Kroupa of the University of Bonn led him to conclude that all stars are born as binaries.(…) We now believe that most stars, which are quite similar to our own sun, form as binaries. I think we have the strongest evidence to date for such an assertion.” “New evidence that all stars are born in pairs” (June 14, 2017)

Interesting, isn’t it? If all stars are born in pairs, how and why did our Sun separate from its original companion? Did they part ways due to hypothetical cosmic ‘turbulences’ and ‘perturbations’ that somehow ruined their primordial, magnetic relationship? If it were eventually found that all stars have a binary companion, this would have profound implications for the entire realm of astrophysics—and this isn’t just my personal opinion: it was none other than Jacobus Kapteyn, the world’s foremost expert in stellar statistics, who famously stated at the end of his illustrious career that:

“If all stars were binaries there would be no need to invoke ‘dark matter’ in the Universe.”

We have seen that modern astronomy studies strongly support the notion that stars are by definition born in pairs. Further on (Chapter 28), we shall see that a very recent study (September 2022) has concluded that stars also die in pairs. As shown above, the evidence that all stars are binary/multiple systems is mounting day by day, yet in the realm of popular science our Sun is still steadfastly claimed to be a single star.

We have all heard of ‘dark matter’, but are never told exactly what it is. This is because nobody really knows. Modern astrophysicists think of it as an elusive, invisible and imponderable ‘stuff’ filling the universe and are desperately attempting to detect it―so far with no luck. It is currently contended that about 80% of the universe consists of dark (or ‘missing’) matter because the observed, highly scattered distributions and the erroneously estimated orbital speeds of celestial bodies and galaxies appear to violate both Kepler’s and Newton’s hallowed laws, as well as the infamous ‘Big Bang’ theory. Here’s an extract from a Wikipedia page titled “Galaxy rotation curve”:

“Since observations of galaxy rotation do not match the distribution expected from application of Kepler’s laws, they do not match the distribution of luminous matter. This implies that spiral galaxies contain large amounts of dark matter or, in alternative, the existence of exotic physics in action on galactic scales. These results suggested that either Newtonian gravity does not apply universally or that, conservatively, upwards of 50% of the mass of galaxies was contained in the relatively dark galactic halo.”

Evidently, Kepler’s and Newton’s laws, which modern astrophysics relies on, are in serious trouble today. Yet, the world’s scientific community does not seem to be much bothered with that. Let us now take a brief look at what is popularly known as black holes.

3.2 Binary stars keep masquerading as black holes

The above title is the actual headline of an article published on sciencenews.org in April 2022. According to this recent discovery, binary stars ‘keep masquerading’ as black holes. In other words, what astrophysicists for decades have been calling black holes may simply be artefacts caused by formerly unsuspected and still undetected binary star systems.

Fig. 3.3 Image source: sciencenews.org

Fig. 3.3 Image source: sciencenews.org

Here’s an extract from the article published on Science News.org on 4 April 2022:

“As astronomy datasets grow larger, scientists are scouring them for black holes, hoping to better understand the exotic objects. But the drive to find more black holes is leading some astronomers astray. “You say black holes are like a needle in a haystack, but suddenly we have way more haystacks than we did before,” says astrophysicist Kareem El-Badry of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. “You have better chances of finding them, but you also have more opportunities to find things that look like them.” Two more claimed black holes have turned out to be the latter: weird things that look like them. They both are actually double-star systems at never-before-seen stages in their evolutions, El-Badry and his colleagues report March 24 in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The key to understanding the systems is figuring out how to interpret light coming from them, the researchers say.” SCIENCE NEWS, April 2022 - “Binary stars keep masquerading as black holes”

So two recently discovered black holes have turned out to be double-star systems at never-before-seen stages in their evolutions. That article is pure dynamite, if you ask me, and is well worth reading in its entirety. But let me submit another excerpt from it:

“The problem was that there was not just one star, but a second one that was basically hiding,” says astrophysicist Julia Bodensteiner of the European Southern Observatory in Garching, Germany, who was not involved in the new study. That second star in each system spins very fast, which makes them difficult to see in the spectra. What’s more, the lines in the spectrum of a star orbiting something will shift back and forth, El-Badry says. If one assumes the spectrum shows just one average, slow-spinning star in an orbit - which is what appeared to be happening in these systems at first glance - that assumption then leads to the erroneous conclusion that the star is orbiting an invisible black hole.”

Amazing, isn’t it? In short, black holes may merely be optical illusions created by binary/multiple star systems, one of the components of which spins too fast to be distinguishable in the spectra. Since this astonishing discovery was made as recently as early 2022, the field of astrophysics may be about to undergo a major revolution. Could all black holes be illusory? Let us read the final lines of the quoted Science News article:

“Everyone was looking for really interesting black holes, but what they found is really interesting binaries,” Bodensteiner says. These are not the only systems to trick astronomers recently. What was thought to be the nearest black hole to Earth also turned out to be pair of stars in a rarely seen stage of evolution. Of course, it’s disappointing that what we thought were black holes were actually not, but it’s part of the process,” Jayasinghe says. He and his colleagues are still looking for black holes, he says, but with a greater awareness of how pairs of interacting stars might trick them.”

In conclusion, currently available evidence suggests dark matter and black holes could be figments of the imagination engendered by our poor understanding of binary systems and ‘optical tricks’ played by their complex interactions.

3.3 The intersecting orbits of the Sun and Mars

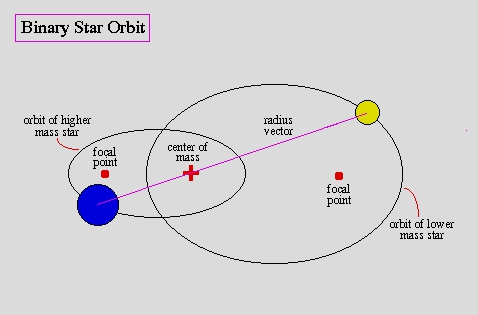

To see what the configuration of the Sun-Mars binary system might look like, let us begin with a classic binary star system.

Fig. 3.4 A classic binary star system, as illustrated in the astronomy literature: a larger and a smaller body revolve in intersecting orbits around a common centre of mass.

Fig. 3.4 A classic binary star system, as illustrated in the astronomy literature: a larger and a smaller body revolve in intersecting orbits around a common centre of mass.

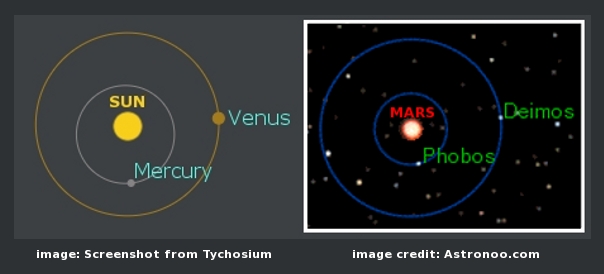

Note that, if we replace the above ‘high-mass star’ and ‘low-mass star’ with the Sun and Mars, respectively, as in the below adaptation, we obtain a neatly balanced binary system that incorporates the two moons of the Sun (Mercury and Venus) and the two moons of Mars (Phobos and Deimos).

Fig. 3.5 In the TYCHOS, Earth is positioned near (or at) the centre of mass of the Sun-Mars binary system. Both the Sun and Mars are escorted by a pair of moons (Venus and Mercury, and Phobos and Deimos).

Fig. 3.5 In the TYCHOS, Earth is positioned near (or at) the centre of mass of the Sun-Mars binary system. Both the Sun and Mars are escorted by a pair of moons (Venus and Mercury, and Phobos and Deimos).

We can see just how harmonious such a binary system would be: our Earth and Moon embraced by the Sun-Mars binary duo, with each of the binary companions hosting a pair of lunar satellites. You may now ask yourself why no one (not even supporters of Brahe’s original model) has envisioned to this day Mars as the Sun’s binary companion; this may be because Mars returns in opposition every two solar years, instead of every single year—as one might expect of a ‘classic’ binary system. Moreover, due to the eccentricity of Mars’ orbit, this 2:1 ratio will fluctuate back and forth over time (it is currently about 2.13:1). However, as will be demonstrated further on, this oscillating ratio will in the long run average out to a precise 2:1 relationship: the Sun will return to the same place in our skies in 25344 years—the ‘Solar Great Year’—whereas Mars will do so in 50688 years (25344 × 2)—i.e., the ‘Martian Great Year’. (Note that, throughout this book, the value of ‘25344’ years will denote the Earth’s Great Year. Yet, since the Earth will have completed a 360° clockwise revolution around its PVP orbit during this time—thus ‘subtracting’ one counter-clockwise solar revolution—the value of ‘25345’ years should be used for the ‘Solar Great Year’).

3.4 Why Mars?

You may now wonder: “Why Mars? Wouldn’t it make more sense if Jupiter, the largest planet in our system, were the Sun’s binary companion?” Well, size is not everything. Let us not forget that Jupiter is considered a ‘gas planet’ while Mars is believed to be composed of mostly iron and rock. There is no way of directly determining and comparing the weight of these two bodies, but I trust we can all agree that the density (hence, the relative weight) of iron and rock are several orders of magnitude greater than that of any gas existing in nature.

Furthermore, aren’t we told that the Sun itself is composed of hydrogen (70%), helium (28%) and a negligible 2% of other, denser elements? Seen in this light, could Mars have a mass similar to that of the Sun, in spite of their ‘David-and-Goliath’ difference in diameter? While this would appeal to the adherents of Newton’s gravitational laws, it should be stated for the record that my research for the TYCHOS model has from day one left Newtonian and Einsteinian physics at the door, so to speak. It has instead focused on the all-important, empirically testable, repeatable and verifiable observational data gathered over the centuries by our world’s most rigorous observational astronomers. To wit, no physical/astrophysical theorems of our solar system can be formulated without having first correctly determined its geometric configuration (doing so would be tantamount to putting the proverbial cart in front of the horse).

Mars is the only body of our solar system that can transit on both sides of Earth in relation to the Sun and whose farthest-to-closest transits from Earth exhibit a whopping 7:1 ratio, with a mean apogee of 400 million km and a mean perigee of 56.6 million km. This is a strong indication that Mars—and no other body in our solar system—is the Sun’s binary companion. The below screenshot from the Tychosium 3D simulator should make this clear:

Fig. 3.6 Mars can transit as close as 56.6 Mkm from Earth (perigee) and as far as 400 Mkm (apogee), representing a 7/1 ratio (400 / 56.6).

Fig. 3.6 Mars can transit as close as 56.6 Mkm from Earth (perigee) and as far as 400 Mkm (apogee), representing a 7/1 ratio (400 / 56.6).

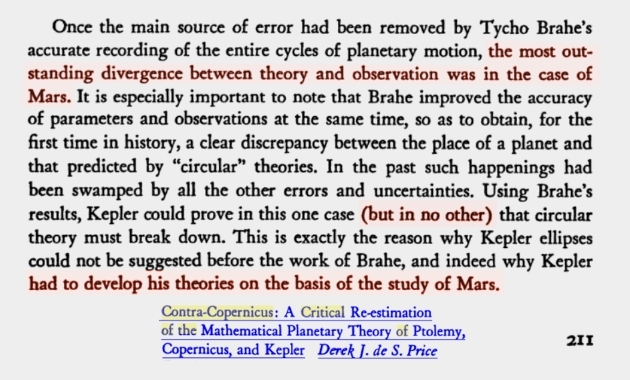

As we shall see in the following chapters, there are many good reasons to think that Mars—and no other body of our system—is the Sun’s binary companion. Perhaps the most interesting evidence of Mars’ uniqueness among the components of our system is the fact that Kepler formulated his entire set of ‘laws’ around the motions of Mars. As astronomy historians have thoroughly documented, Kepler, who was recruited by Brahe for the sole purpose of resolving the ‘incomprehensible behaviour’ of Mars, spent over half a decade in what he called his “war on Mars”, obsessively trying to solve the befuddling Martian riddle. Mars was truly the greatest challenge posed by Brahe’s exceptionally accurate observational tables.

Fig. 3.7 Extract from “Contra Copernicus” by Derek J. de S. Price

Fig. 3.7 Extract from “Contra Copernicus” by Derek J. de S. Price

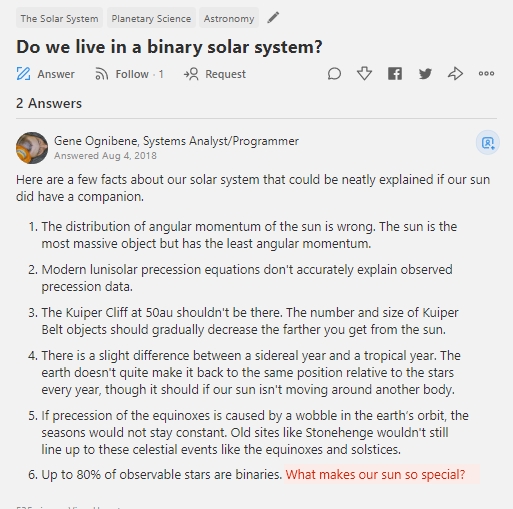

As for why the Sun is likely to have a binary companion, Gene Ognibene posted the following 6 points well worth the read:

Fig. 3.8

Fig. 3.8

3.5 Comparing the moons of the Sun and Mars

In the TYCHOS model, Mercury and Venus are moons of the Sun. Similarly, Mars has two lesser-known, ‘tidally locked’ moons: Phobos and Deimos. The Martian moons were discovered by Asaph Hall as recently as 1877, meaning that Brahe, Newton and Kepler were all unaware of their existence.

Fig. 3.9 The moons of the Sun and Mars: Mercury and Venus, and Phobos and Deimos

A closer look at the moons of Mars brings up some interesting interrelationships with their larger counterparts, Mercury and Venus. Under the Copernican model, according to which Mars is just another planet orbiting the Sun, there would be no conceivable reason for these four celestial bodies to exhibit any sort of ‘synchronicity’ with each other. In the TYCHOS model, on the other hand, this is one of many ‘harmonious resonances’ that seem to pervade our solar system, as will be thoroughly expounded further on.

Consider these comparative facts about the moons of the Sun (Mercury and Venus) and the moons of Mars (Phobos and Deimos).

→ Venus’ diameter is about 2.5 times larger than Mercury’s diameter.

→ Deimos’ orbital diameter is about 2.5 times larger than Phobos’ orbital diameter.

→ Phobos’ diameter is about 1.8 times larger than Deimos’ diameter.

→ Venus’ orbital diameter is about 1.8 times larger than Mercury’s orbital diameter.

It may at first sound bizarre to compare orbs’ diameters to orbital diameters (apples and oranges?), unless you know that our Moon revolves around the Earth in the same time as the Sun rotates around its axis (~27.3 days, the so-called Carrington number). Curious, isn’t it? To my knowledge, you won’t find any mention of these remarkable ’reciprocities’ in astronomy literature.

Furthermore: Each year, Mercury revolves about 3.13 times around the Sun, whereas each day Phobos revolves 3.13 times around Mars. For the sake of comparison, think of the Sun as revolving once every year around Earth, whereas the Earth rotates once every day around its axis.

All this appears to indicate an affinity between these two pairs of moons, something Copernicans would have to attribute to happenstance. Conversely, under the TYCHOS model, these orbital resonances can be interpreted as a natural consequence of the interrelation between the Sun’s moons (Mercury and Venus) and Mars’ moons (Phobos and Deimos).

You might now justly ask yourself: “Why are Mercury and Venus the only ‘planets’ of our solar system with no moons of their own?” As a matter of fact, this is one of astronomy’s longstanding ‘mysteries’. The truth of the matter is: no Copernican astronomer actually knows why Venus and Mercury are moonless, and no compelling theses on this vexing subject have been advanced to this day. Here are, for instance, NASA’s timid and tentative explanations of this major cosmic enigma:

“Most likely because they are too close to the Sun. Any moon with too great a distance from these planets would be in an unstable orbit and be captured by the Sun. If they were too close to these planets they would be destroyed by tidal gravitational forces. The zones where moons around these planets could be stable over billions of years is probably so narrow that no body was ever captured into orbit, or created in situ when the planets were first being accreted.” “Why don’t Mercury and Venus have moons?” by NASA for Imager for Magnetopause-to-Aurora Global Exploration

Here’s a rather more intellectually honest statement found on another NASA webpage:

“Why Venus doesn’t have a moon is a mystery for scientists to solve.” “How many moons?” by Kristen Erickson for NASA Space Place (2017)

As it is, the TYCHOS model has a simple answer to this ‘mystery’: Venus and Mercury have no moons due to the simple fact that they are moons themselves. In fact, the notion that Venus and Mercury are moons rather than planets can be deduced and backed up in multiple ways. What follows should make it glaringly obvious that Mercury and Venus are moons, not planets.

3.6 Rotational resonances between our Moon, Mercury and Venus

• The Moon rotates around its axis and revolves around the Earth in 27.322 days (or 655.73 hours). The Moon’s circumference is 10920.8 km. Hence, a distance of 10920.8 km covered in 655.73 hours computes to an equatorial rotational speed of 16.65 km/h.

• Mercury rotates around its axis and returns to perigee in ~116.88 days (or 2805.12 hours). Mercury’s circumference is 15329 km. Hence, a distance of 15329 km covered in 2805.12 hours computes to an equatorial rotational speed of 5.465 km/h.

• Venus rotates around its axis and returns to perigee in ~584.4 days (or 14025.6 hours). Venus’ circumference is 38024.5 km. Hence, a distance of 38024.5 km covered in 14025.6 hours computes to an equatorial rotational speed of 2.711 km/h.

These rotational speeds are of course exceptionally slow, compared to those of all the other bodies in our Solar System. In fact, they are all in the speed range of a children’s merry-go-round. In contrast, Jupiter’s equatorial rotational speed is a brisk 43000 km/h, and Saturn’s is about 37000 km/h. Such hypersonic speeds are completely unlike the sluggish rotational speeds of moons.

Note also the following interesting facts and resonances:

• Venus’ mean perigee-to-perigee period is exactly 5 times longer than that of Mercury (whose equatorial rotational speed is near-exactly twice that of Venus).

• The Moon’s equatorial rotational speed (16.65 km/h) is about 100 times slower than that of the Earth’s (1670 km/h) and roughly 10 times faster than the Earth’s orbital speed (1.6 km/h).

• The Moon’s rotational speed (16.65 km/h) is approximately 3 times that of Mercury (5.465 km/h) and 6 times that of Venus (2.711 km/h). Incidentally, this 6:3:1 rotational resonance between the Moon, Mercury and Venus is somewhat reminiscent of the notorious 4:2:1 orbital resonance between Io, Europa and Ganymede (the moons of Jupiter) known in astronomy as the ‘Laplace resonance’.

Further on (Chapter 20), we shall have a look at Mars’ true axial rotational period which, when assessed in light of the TYCHOS model, turns out to be synchronous with Earth’s (~24 hours). In any event, the fact that astronomers have never even entertained the possibility that Venus and Mercury might be solar satellites rather than planets―what with their evidently lunar rotational speeds and behaviour―is in itself a mystery.

Definition of a moon or lunar body

Based on the above, the characteristics that set moons apart from planets may be summarized thus:

• No moons have satellites of their own, since they are moons themselves.

• Moons rotate exceptionally slowly around their own axes compared to all other celestial bodies.

• Moons always show the same face to their host star or planet (in astronomy jargon: they are ‘tidally locked’).

In the next chapter, I will illustrate the basic configuration of the TYCHOS model and introduce you to the interactive Tychosium 3D simulator. Although it may seem somewhat premature to unveil it at this early stage of the book, an overview of the TYCHOS model’s configuration is necessary to understand the subsequent chapters.