Chapter 9: Tilts, obliquities and oscillations

9.1 Kepler’s accelerating and decelerating planets

Earth’s well-known 23.4° axial tilt is a fundamental requisite for the Copernican model to work, since Earth’s obliquity is meant to account for our alternating seasons. The most popularly held, yet academically supported, theory as to exactly why Earth’s axis would be skewed goes like this:

“When an object the size of Mars crashed into the newly formed planet Earth around 4.5 billion years ago, it knocked our planet over and left it tilted at an angle.” “What Is Earth’s Axial Tilt or Obliquity?” - Time and Date website

Yet, and in spite of such a fanciful explanation for Earth’s tilt, Copernicans also believe that our planet slowly wobbles around its own axis. In the TYCHOS model, the Earth is indeed tilted at 23.4° in relation to its orbital plane, yet with some notable differences: it is the Sun that revolves around the Earth, while our planet’s own orbital motion proceeds at the tranquil speed of 1.6 km/h, with our northern hemisphere at all times ‘leaning outwards’, towards the Sun’s external orbital path.

Interestingly, it is beyond dispute among geophysicists that our planet’s northern hemisphere is ‘heavier’ than its southern hemisphere. It is estimated that over two thirds (68%) of the Earth’s land mass is in the northern hemisphere, meaning that our planet is ‘top heavy’. This notion is almost universally accepted by both mainstream and ‘dissident’ scientists:

“The northern hemisphere consists of the great land masses and higher elevations, from a mechanical aspect, the Earth is top heavy, the northern hemisphere must attract a stronger pull from the Sun than the southern hemisphere. This lack of uniformity should impact on the movements of the Earth.” “Big Bang or Big Bluff” (p.164) by Hans Binder (2011)

It would thus seem intuitively logical, even to devout Newtonian advocates, that Earth’s heavier hemisphere would hang ‘outwards’ as our planet goes around its Polaris-Vega-Polaris (PVP) orbit. Conversely, it is hard to fathom how and why Earth’s axis would maintain a fixed, peculiar inclination while circling around the Sun (whilst also wobbling around its axis), as posited by the heliocentric theory. In fact, one of the latter’s most problematic aspects has to be its proposed cause for the observed secular stellar precession and our alternating pole stars. As will be expounded in Chapter 10, the hypothesis of a ‘third motion’ of Earth—a slow, retrograde wobble of Earth’s polar axis—has been roundly disproven in recent years.

As illustrated in Figure 9.1, the TYCHOS model provides an uncomplicated solution to the enigma of the General Precession and our alternating pole stars: the phenomenon is simply due to Earth’s slow, ‘clockwise’ motion around the PVP orbit, completed in 25344 years. Our current northern and southern pole stars are Polaris and Sigma Octantis, but over time these will be replaced by other stars, namely Vega (~11000 years from now) and Eta Columba (~12000 years from now).

Fig. 9.1 How the PVP orbit causes the pole stars to alternate.

Fig. 9.1 How the PVP orbit causes the pole stars to alternate.

The fact that Earth is tilted may also explain why the Sun is further from Earth around July and closer to Earth around January, the difference being 5 Mkm (152.1-147.1 Mkm, or 3.3%). As a matter of fact, the Sun is observed to be about 3.3% smaller in July than in January, regardless of which earthly hemisphere it is viewed from (incidentally, one wonders how flat earth proponents would account for this particular empirical observation).

Fig. 9.2

Fig. 9.2

If we envision the Earth’s magnetic charge as a repelling force which prevents the Sun from ‘falling into it’, the force would likely peak around summer solstice in the northern hemisphere when the ‘heavier’ part of the globe is maximally tilted towards the Sun (Figure 9.3). Six months later, when the southern and ‘lighter’ hemisphere is maximally tilted towards the Sun, the repelling force would wane somewhat, allowing the Sun to get a little closer to Earth. However speculative this scheme for the Earth’s axial tilt and the variation in the Earth-Sun distance may seem, it is worthwhile to consider, were it only as a point of departure for future inquiry.

Fig. 9.3 Speculative scheme of the magnetic influence of Earth on the Earth-Sun distance.

Fig. 9.3 Speculative scheme of the magnetic influence of Earth on the Earth-Sun distance.

The 3.3% annual variation in the distance between the Earth and the Sun may explain why Kepler claimed that all the bodies in the solar system keep accelerating and decelerating. Kepler’s model has Earth travelling around the Sun while alternately speeding up and slowing down. In the TYCHOS model, of course, the annually orbiting body is not the Earth, but the Sun. The below orbital velocities, attributed to the Earth by mainstream astronomers, would therefore apply to the Sun.

According to a NASA Fact Sheet:

EARTH’s max. orbital velocity: 30.29 km/s

EARTH’s min. orbital velocity: 29.29 km/s

Difference: 3.3%

Annual variation in the distance between the Earth and the Sun: 3.3%.

Note that this is no small variation. It means Earth would have to speed up by as much as 3600 km/h (about 3 times the speed of sound) between July and January. But how to account for such hefty, yet formidably consistent, speed variations? Well, the Copernican astronomers’ explanation is that, due to the Sun’s ‘gravitational pull’, the closer a planet is to the Sun, the faster it will travel.

However, one has to wonder how the Sun’s ‘gravitational pull’, exerted perpendicularly to a given planet’s orbit, could cause it to speed up and slow down, linearly. Yet, this is what Kepler was forced to conclude in order to ‘make things work’. I trust the astute reader has already perceived a far more obvious explanation for these apparent velocity fluctuations: quite simply, since the Sun transits 3.3% closer to Earth in January (perigee) than it does in July (apogee), it will be perceived to travel 3.3% faster in relation to the firmament. In reality, though, the Sun always travels at a constant speed (29.78 km/s), and so do all the other bodies in the system. In other words, their apparent orbital speed variations are an optical illusion caused by changes in relative distance and spatial perspective.

9.2 Venus and the Sun’s 5 Mkm oscillation

What follows is something that will require the reader to return for a second reading later on to fully appreciate its remarkable nature and significance. For now, suffice to say that the TYCHOS model submits that Earth’s orbital diameter (i.e. the diameter of the PVP orbit, as expounded in Chapter 11) is 113.2 Mkm. Venus is often referred to as ‘Earth’s sister’ because it is almost the same width as Earth (12103.6km versus 12756km respectively). According to all official estimates, the average Sun-Venus distance is 108.2 Mmkm. As illustrated in Section 9.1, the Earth-Sun distance varies by about 5 Mkm between winter and summer. Thus, since Venus is a moon of the Sun, as posited by the TYCHOS model, it should also oscillate in relation to the Earth by 5 Mkm between summer and winter. In other words, the maximum Earth-Venus distance would add up to 113.2 Mkm (108.2Mkm + 5Mkm), a figure that would seem to ‘reflect’ the diameter of Earth’s PVP orbit. The significance of this is unclear, yet it certainly merits further investigation.

9.3 The Sun’s ‘mysterious’ 6 or 7-degree tilt

“It’s such a deep-rooted mystery and so difficult to explain that people just don’t talk about it.”

You may never have heard of it, but one of the most baffling mysteries in astronomy is the 6° (or 7°) tilt of the Sun. Others refer to it as “the common plane of all of our planets’ orbits with respect to the Sun’s polar axis”. Make no mistake: the observable fact that the Sun’s axis is tilted at an angle with respect to the entire solar system’s plane is no petty matter. For why would this be? Isn’t the Sun supposed to be the massive ‘central driveshaft’ of the system? Shouldn’t therefore all our planets’ orbits be co-planar with the Sun’s equator? Well, they are not, and this fact is an absolute mystery for academic astronomy—an unresolved quandary which all by itself falsifies both Newton’s and Einstein’s edicts. As recently as 2016, an academic study admitted that it’s “such a deep-rooted mystery and so difficult to explain that people just don’t talk about it”. The study went on, bizarrely enough, to speculate that this tilt of the Sun’s axis might be caused by what they call “Planet Nine”, a hitherto unseen and entirely hypothetical celestial body!

The long-standing tilt riddle is admittedly “a big deal” for mainstream astronomers:

“All of the planets orbit in a flat plane with respect to the sun, roughly within a couple degrees of each other. That plane, however, rotates at a 6-degree tilt with respect to the sun — giving the appearance that the sun itself is cocked off at an angle. Until now, no one had found a compelling explanation to produce such an effect. ‘It’s such a deep-rooted mystery and so difficult to explain that people just don’t talk about it,’ says Brown, the Richard and Barbara Rosenberg Professor of Planetary Astronomy.” “Curious tilt of the Sun traced to undiscovered planet” - by the California Institute of Technology (2016)

“The Sun’s rotation was measured for the first time in 1850 and something that was recognized right away was that its spin axis, its north pole, is tilted with respect to the rest of the planets by 6 degrees. So even though 6 degrees isn’t much, it is a big number compared to the mutual planet-planet misalignments. So the Sun is basically an outlier within the solar system. This is a long-standing issue and one that is recognized but people don’t really talk much about it. Everything in the solar system rotates roughly on the same plane except for the most massive object, the Sun — which is kind of a big deal.” “Planet Nine may be responsible for tilting the Sun” - by Shannon Stirone (2016)

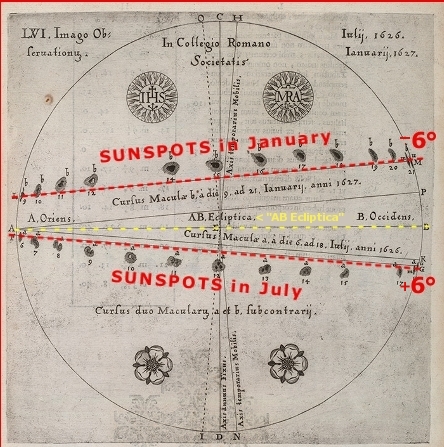

As you will remember, in Chapter 6 we saw that the rotational axes of both Mars and our own Moon are also inclined by about 7° degrees, a remarkable fact heliocentrists are hard pressed to explain. As it turns out, the 6° (or 7°) tilt of the Sun’s rotational axis with respect to our ecliptic plane was known long before 1850. It was discovered by Christoph Scheiner back in the 1600s during his extensive 20-year-long sunspot observations. His work was richly illustrated and published in his monumental treatise Rosa Ursina (1630). In fact, the sunspot issue triggered a bitter and infamous 30-year-long feud between Galileo and Scheiner (who, incidentally, was a staunch supporter of the Tychonic model). To be sure, the observed inclination of the Sun is no trivial matter, but a true bone of contention in the endless debate between heliocentrists and geocentrists.

“Scheiner, in his massive 1630 treatise on sunspots entitled ‘Rosa Ursina’, accepted the view of sunspots as markings on the solar surface and used his accurate observations, to infer the fact that the Sun’s rotation axis is inclined with respect to the ecliptic plane.” “1610: First telescopic observations of sunspots, Solar Physics Historical Timeline” - by UCAR/NCAR (2018)

Fig. 9.4 Illustration by Cristoph Scheiner, with the 6° inclination of his observed sunspot transits in January and July highlighted in red.

Fig. 9.4 Illustration by Cristoph Scheiner, with the 6° inclination of his observed sunspot transits in January and July highlighted in red.

The Sun’s north pole tilts towards us in September and away from us in March, as described in a paper by Bruce McClure:

“The Sun’s axis tilts almost 7.5 degrees out of perpendicular to Earth’s orbital plane. (The orbital plane of Earth is commonly called the ecliptic.) Therefore, as we orbit the Sun, there’s one day out of the year when the Sun’s North Pole tips most toward Earth. This happens at the end of the first week in September. Six months later, at the end of the first week in March, it’s the Sun’s South Pole that tilts maximumly towards Earth. There are also two days during the year when the Sun’s North and South Poles, as viewed from Earth, don’t tip toward or away from Earth. This happens at the end of the first week in in June, and six months later, at the end of the first week of December.” “The Tilt of the Sun’s Axis” by Bruce McClure (2006)

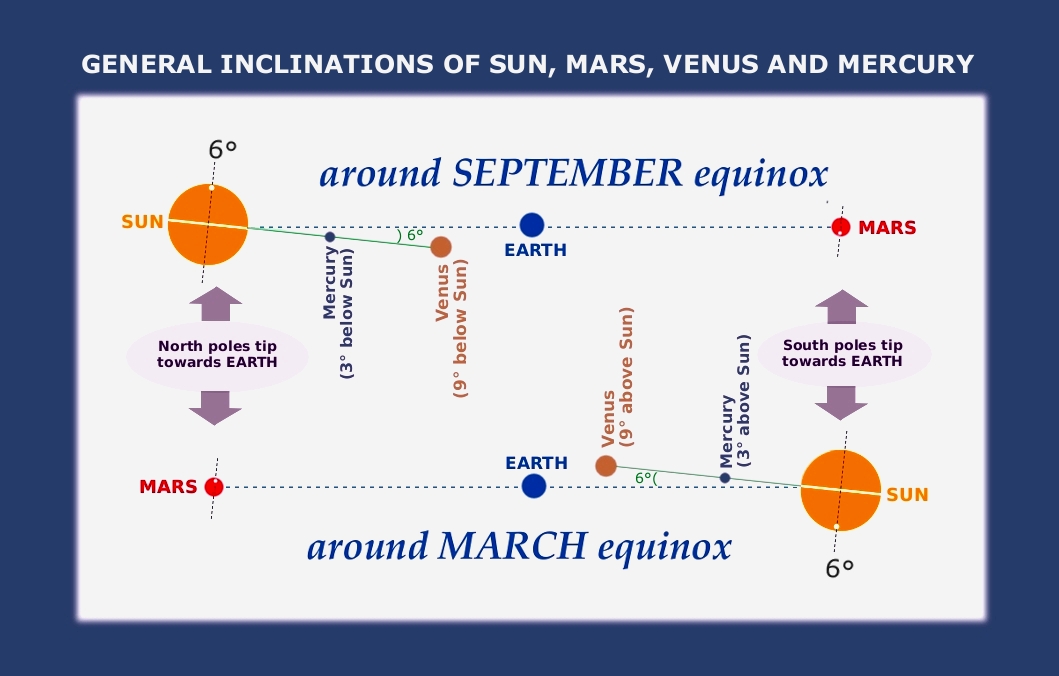

In the TYCHOS model, this 6° (or 7°) tilt of the Sun can be illustrated as follows:

Fig. 9.5

Fig. 9.5

Figure 9.6 is based on another of Scheiner’s illustrations, showing how he personally observed the movement of two sunspots around the solar sphere in the month of March:

Fig. 9.6

Fig. 9.6

Note that the inclination marked in red as 23° is simply caused by Earth’s own axial tilt. What concerns us in Scheiner’s drawing is the tilt highlighted in yellow arrows and blue arcs. It’s hard to make out exactly what amount of inclination they show, but 6 or 7 degrees would seem to be a fair estimate. In any case, the drawing clearly indicates that the Sun’s north pole tilts away from Earth in the month of March. We may also be satisfied that the Sun’s polar axis is indeed tilted by 6° or 7° in relation to the ecliptic.

9.4 Are the orbits of Venus and Mercury co-planar with the Sun’s axial tilt?

We shall now proceed to verify whether the orbits of Sun’s two moons, Venus and Mercury, can be correlated with the Sun’s 6° or 7° tilt. Official astronomy provides the following figures for the orbital tilts of Venus and Mercury:

Orbital tilt of Venus: 3.4°

Orbital tilt of Mercury: 7°

In reality however, Venus can from our earthly perspective be observed to be as many as 9° below or above the Sun. Again, spatial perspective can be misleading as it depends on several factors, such as relative distances and inclinations.

Whenever Venus transits in perigee in September, we see it below the Sun by about -9°.

Whenever Venus transits in perigee in March, we see it above the Sun by about +9°.

Whenever Mercury transits in perigee in September, we see it below the Sun by about -3°.

Whenever Mercury transits in perigee in March, we see it above the Sun by about +3°.

Fig. 9.7

Fig. 9.7

On the other hand, whenever MERCURY transits in perigee in September, we see it BELOW the Sun (by about -3°, as viewed from the Earth); and Whenever MERCURY transits in perigee in March, we see it ABOVE the Sun (by about +3°, as viewed from the Earth).

The TYCHOS model allows to make a conceptual illustration of the above empirical observations (Fig. 9.8)

Fig. 9.8 Venus’ and Mercury’s orbits can be shown to be co-planar with the Sun’s tilt.

Fig. 9.8 Venus’ and Mercury’s orbits can be shown to be co-planar with the Sun’s tilt.

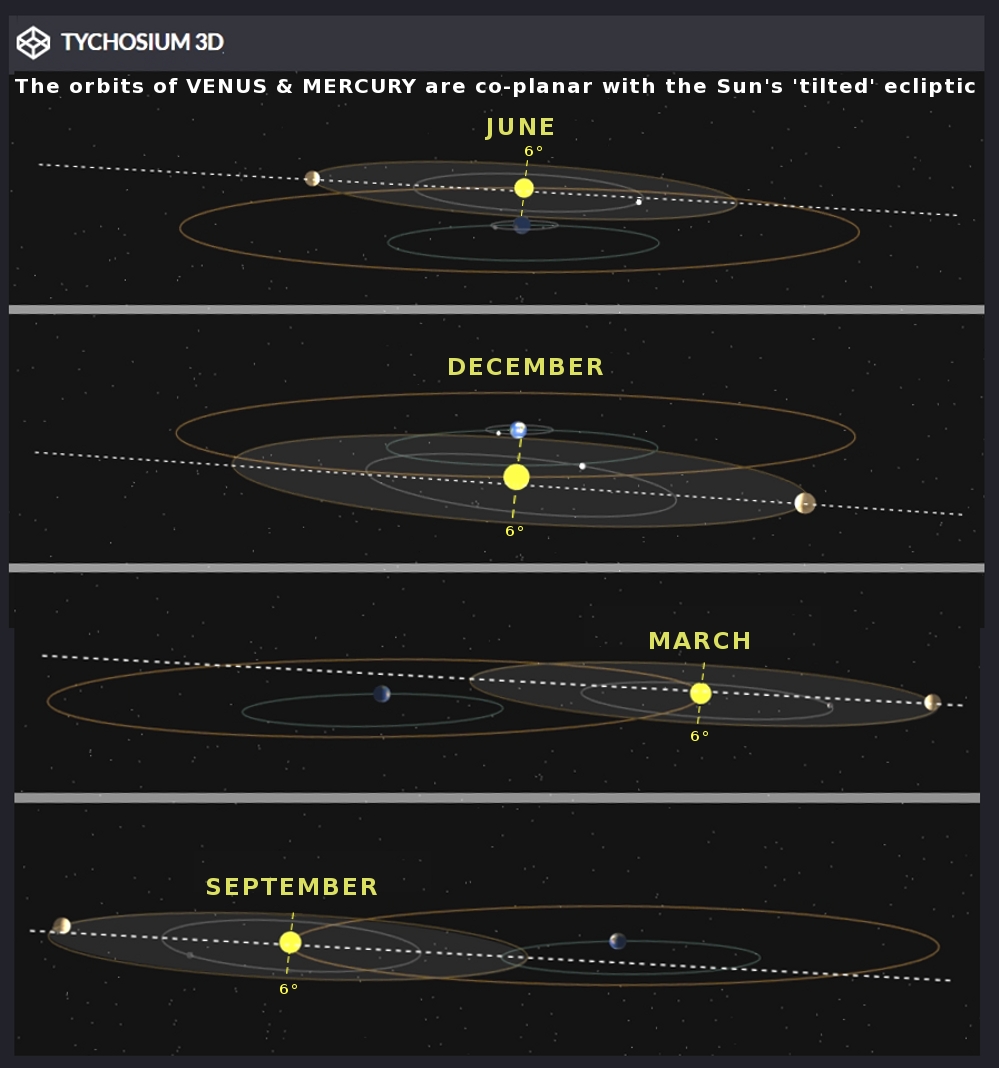

Unsurprisingly, heliocentric astronomers do not seem ever to have noticed or debated this stunning fact. But then, you may ask, does the Tychosium 3D simulator show the orbits of Venus and Mercury to be co-planar with the Sun’s axial tilt? Indeed it does: as you can personally verify, the Tychosium 3D simulator shows how the virtual ‘disk’ that encompasses the orbits of Venus and Mercury around the Sun remains permanently tilted by about 6° or 7° in relation to the Sun’s orbital plane. Whether the Copernicans like it or not, the orbits of Venus and Mercury are demonstrably co-planar with the Sun’s axial tilt. The following four screenshots from the Tychosium 3D simulator illustrate the fact:

Fig. 9.9 The orbits of Venus and Mercury are co-planar with the Sun’s tilted ecliptic

Fig. 9.9 The orbits of Venus and Mercury are co-planar with the Sun’s tilted ecliptic

One could not wish for stronger and more spectacular evidence that Venus and Mercury are the two lunar satellites of the Sun. As it is, Venus and Mercury are not just the only moonless ‘planets’ of our solar system, they are also the only two bodies whose orbits are fine-tuned to the Sun’s axial tilt. Everything suggests that we ought to start referring to them as ‘moons of the Sun’, instead of ‘planets’. Add to this the fact, expounded in Chapter 6 (Section 6.3), that our own Moon’s rotational axis is also tilted by about 7° in relation to the ecliptic, meaning the Moon is actually fine-tuned to the Sun, Venus, Mercury and Mars, and even to the observed inclination of the Sirius system! To what, one may ask, would the advocates of the heliocentric model attribute this wondrous accord? Try submitting this question to your local astronomy professor, but prepare to be treated with disdain.

9.5 The Sun’s 79-year cycle and 39.5-year oscillation period

The Sun is observed to slightly oscillate around its own nucleus. According to current theory, the reason for this oscillation is the extra-solar location of the system’s ‘center of mass’:

“The center of mass of our solar system is very close to the Sun itself, but not exactly at the Sun’s center (it is actually a little bit outside the radius of the Sun). However, since almost all of the mass within the solar system is contained in the Sun, its motion is only a slight wobble in comparison to the motion of the planets.” “Does the Sun orbit the Earth as well as the Earth orbiting the Sun?” by Cathy Jordan / Cornell University (2015)

According to the Wikipedia, what is observed is actually “the motion of the solar system’s barycenter relative to the Sun”.

“The barycenter (or barycentre) is the center of mass of two or more bodies that are orbiting each other, or the point around which they both orbit. It is an important concept in fields such as astronomy and astrophysics. The distance from a body’s center of mass to the barycenter can be calculated as a simple two-body problem. In cases where one of the two objects is considerably more massive than the other (and relatively close), the barycenter will typically be located within the more massive object. Rather than appearing to orbit a common center of mass with the smaller body, the larger will simply be seen to wobble slightly.”

The Wikipedia goes on to say that the Sun’s observed wobble/oscillation is caused by “the combined influences of all the planets, comets, asteroids, etc. of the solar system”. However, the TYCHOS model allows us to explore other possibilities, such as the direct influence of the Sun’s binary companion, Mars. After all, such subtle oscillations on the part of host stars in binary systems are precisely what our modern-day astronomers look for, with their sophisticated spectrometers and assorted state-of-the-art techniques, when trying to determine if a given star may host a smaller binary companion. In light of this, it seems perfectly reasonable to attribute the Sun’s small oscillation around its nucleus to ordinary binary system physics.

Earlier on we saw how Mars has a distinctive 79-year cycle within which it returns to the same celestial location. As it is, even Mercury, the Sun’s junior moon, exhibits a 79-year cycle and thus conjuncts regularly with Mars every 79 years. Now, it turns out that, according to modern-day researchers of solar activity, the Sun also has a 79-year cycle. According to studies conducted by Theodor Landscheidt, the cycle of solar activity is related to the sun’s oscillatory motion about the center of mass of the solar system.

Theodor Landscheidt (1927-2004) is held in the highest esteem by many independent astronomers and climatologists who have noticed that our Earth’s climate is correlated to the periodic fluctuations of solar activity, which themselves depend on the Sun’s observed oscillations around the “center of mass of the planetary system (CM)” – to use Landscheidt’s own words. Now, as their theory goes, this observed oscillation of the Sun would be caused by the gravitational pull of the larger planets of our system (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune). Some say that even Mercury and Venus may be involved in this collective “solar nudging”. Oddly enough, Mars – and Mars only – is never mentioned in their papers, despite Landscheidt’s discovery of the Sun’s peculiar 79-year synchronicity with Mars.

Table 9.1 Swinging Sun, 79-Year Cycle, and Climatic Change - by T. Landscheidt (1981)

Table 9.1 Swinging Sun, 79-Year Cycle, and Climatic Change - by T. Landscheidt (1981)

Interestingly, Landscheidt also points out that the Sun’s nucleus and center of mass “can come close together (i.e., return to the same place in space) as in 1951 and 1990”, that is, within a ~39.5-year period. The study features the well-known diagram shown in Figure 9.11, plotting the Sun’s observed oscillation around its own center of mass. I have borrowed and captioned the diagram to highlight the fact that the Sun’s center of mass returns to the same place in approximately 39.5 years. Since the Sun and Mars are locked in a 2:1 orbital ratio, it would stand to reason that the Sun exhibits such a period, since Mars exhibits a 79-year (39.5 x 2) orbital cycle. Just as the Sun revolves twice for every Mars revolution, the Sun’s nucleus would complete two 39.5-year oscillatory periods for every 79-year cycle of Mars.

Fig. 9.10 In the TYCHOS model, Mars and the Sun are binary companions. The two are locked in a 2:1 orbital ratio. Mars has a well-known 79-year cycle in which it returns to the same place, i.e., its oppositions occur at the same longitude. ’B’ marks the Sun’s center of mass, to which it returns in about 39.5 years, or 79/2.

Fig. 9.10 In the TYCHOS model, Mars and the Sun are binary companions. The two are locked in a 2:1 orbital ratio. Mars has a well-known 79-year cycle in which it returns to the same place, i.e., its oppositions occur at the same longitude. ’B’ marks the Sun’s center of mass, to which it returns in about 39.5 years, or 79/2.

Above graphic from p. 44, “Sun-Earth-Man: a Mesh of Cosmic Oscillations” by Theodor Landscheidt (1989). Landscheidt’s caption for the graphic reads:

“Master cycle of the solar system. Small circles indicate the position of the center of mass of the planetary system (CM) in the ecliptic plane relative to the Sun’s center (cross) for the years 1945 to 1995. The Sun’s center and CM (center of mass) can come close together, as in 1951 and 1990 (ed- i.e. ca. 39.5 years) or reach a distance of more than two solar radii.” “The Golden Section: A Cosmic Principle” - by Theodor Landscheidt (1993)

Other independent authors have detected a peculiar “80-y/40-y” periodicity (an approximation of the TYCHOS model’s 79-y/39.5-y periodicity) in relation to the Sun’s barycentric dynamics and what is termed “solar angular momentum inversions”:

“We apply our results in a novel theory of Sun-planets interaction that it is sensitive to Sun barycentric dynamics and found a very important effect on the Sun´s capability of storing hypothetical reservoirs of potential energy that could be released by internal flows and might be related to the solar cycle. This process (which lasts for ca. 80 yr) begins about 40 years before the solar angular momentum inversions, i.e., before Maunder Minimum, Dalton Minimum, and before the present extended minimum.” “Dynamical Characterization of the Last Prolonged Solar Minima” by Rodolfo Gustavo Cionco and Rosa Hilda Compagnucci (2010)

In any event, the observed ‘wobble’ or oscillatory motion of the Sun and its 39.5-year periodicity would certainly seem to lend additional support to the notion that the Sun and Mars constitute a binary system locked in a 2:1 ratio.

9.6 Galileo and Scheiner

As a brief anecdotal aside, it is interesting to note that Galileo (a staunch crusader for Copernicus’ theories) seemingly perceived Cristoph Scheiner’s sunspot observations as a threat to heliocentrism. The notoriously ill-tempered Galileo engaged in fierce verbal battles with numerous astronomers of his time, often wrongfully claiming primacy over new discoveries made by others with the aid of the telescope. Outraged by Galileo’s accusations of plagiarism regarding the discovery of the sunspots, Scheiner decided to move from Ingolstadt to Rome in order to better defend his work. The feud between Galileo and Scheiner soon escalated. Galileo did not refrain from smearing his German colleague, calling him “brute”, “pig”, “malicious ass”, “poor devil” and “rabid dog”!

Fig. 9.11 Galileo writes about his sunspot-rival Scheiner. “On Sunspots” - Translations of letters by Galileo Galilei and Christoph Scheiner, University of Chicago Press (2010)

Fig. 9.11 Galileo writes about his sunspot-rival Scheiner. “On Sunspots” - Translations of letters by Galileo Galilei and Christoph Scheiner, University of Chicago Press (2010)

One may thus be forgiven for questioning the legacy of this most revered ‘science icon’, what with his dreadful arrogance and contempt of his peers. In any case, Galileo’s most acclaimed telescopic discoveries (the phases of Venus and the moons of Jupiter, both of which had, in fact, been previously observed by other astronomers) did not contradict in any way the Tychonic model which, in his time, and as few people will know today, was the predominant ‘system of the world’. What’s more, in his writings, Galileo virtually ignored the widely accepted geoheliocentric model proposed by Brahe and Longomontanus.

“After 1610, when Galileo engaged himself fully in astronomy and cosmology, he showed little direct interest in Tycho’s system and none at all in Longomontanus’ version of it. (…) Moreover, he never mentioned explicitly the Tychonian world system by name.” “Galileo in early modern Denmark, 1600-1650” - by Helge Kragh

One must wonder why Galileo Galilei, the man hailed as the ‘father of the scientific method’, would have been so dismissive of his illustrious Danish colleagues and instead used Ptolemy and his already moribund geocentric system as a straw man in order to forward his heliocentric convictions. The reason why Galileo ‘passed over’ the Tychonic (or semi-Tychonic) system will forever remain a mystery, and it certainly doesn’t say much about his adherence to the scientific method. To be sure, Galileo never provided any sort of evidence for the Earth’s supposed revolution around the Sun. The only argument he put forth towards this idea—his infamous “tide theory”—proved to be entirely spurious:

“Clearly inspired by the behaviour of water when boats come to a halt, Galileo Galilei concluded that the ebb and flow of the tides resulted, similarly, from the acceleration and deceleration of the oceans. This, in turn, was caused by the movement of the Earth around the Sun, and its rotation on its own axis. However, Galileo was completely mistaken in this theory.” “Defeated by the Tides” by Jochen Büttner (2014)

In the next chapter, we shall tackle the so-called ‘third motion of Earth’ and see if the idea that the Earth slowly wobbles around its axis, in the opposite direction of its axial rotation, holds any water. Spoiler: it does not!