Chapter 17: “The Great Inequality” - solved by the TYCHOS

17.1 Perturbations and mathemagics

Back in the 18th century, the spiny question of the observed behavior of Jupiter and Saturn ignited a titanic and long-winded debate among our world’s most celebrated astronomers and mathematicians, including Halley, Flamsteed, Euler, Lagrange, Laplace and Poincaré. What every astronomy historian will know as ‘the Great Inequality’ is a scientific saga of epic proportions. In short, the problem was that the motions of Jupiter and Saturn seemed to obey neither the Newtonian gravitational ‘laws’, nor the Keplerian elliptical ‘laws’. Not a trivial problem, you may say. Surely, Newton and Kepler couldn’t possibly both be wrong … or could they?

What had been observed, first by Kepler himself and later by Halley, was that Jupiter appeared to accelerate while Saturn appeared to decelerate. This was truly ominous news for mankind: it meant, according to Newton’s ‘laws’ of gravity, that Jupiter would inevitably end up crashing into the Sun, while Saturn would be driven into the depths of space!

As we shall see, the TYCHOS can show that these apparent accelerations and decelerations are completely illusory and that our Solar System is not threatened by any looming planetary catastrophe. But let us first see how the eminent Astronomical Journal described the alarming discovery of ‘the Great Inequality’ back in 1895:

Fig. 17.1

Fig. 17.1

Make no mistake, this was no petty matter: the very stability of our Solar System was believed to be at stake. In fact, the Paris and Berlin Academies set up special prizes to encourage scientists to resolve this pesky and ‘potentially apocalyptic’ problem. Leonhard Euler, the most acclaimed Swiss mathematician of all times, was the first awardee, although his calculations showed both Jupiter and Saturn accelerating, contrary to any empirical astronomical observations ever made.

Isaac Newton was also well aware of the problem of the presumed ‘instability’ of our Solar System, based on the observed behavior of Jupiter and Saturn, but he never tackled the troublesome matter, preferring to leave it up to God to eventually restore the ‘chaotic’ planetary motions to order. Kepler also declined the challenge in the hope that future generations would unveil the mystery of our Solar System’s apparent instability. For once, Kepler was right about something.

Now, what you need to know is that, as seen from Earth, Jupiter and Saturn appear to conjunct at roughly the same celestial longitude every 60 years or so. Since Jupiter employs 12 years to circle around us, while Saturn employs 30 years to do so, the two will regularly ‘meet up’ every 60 years (60 = 5 x 12 or 2 x 30, respectively). However, these 60-year conjunctions of Jupiter and Saturn appear to precess anti-clockwise, as illustrated below:

Fig 17.2 Source: “Les conjonctions triples Jupiter-Saturne” by Jean Meeus (1980)

Fig 17.2 Source: “Les conjonctions triples Jupiter-Saturne” by Jean Meeus (1980)

The extract in Figure 17.3 gives an idea of the utter perplexity caused by ‘the Great Inequality’ and how it got the entire astronomy establishment of the time on their toes:

Fig 17.3 Source: “Saturn and its System” by Richard Anthony Proctor (1865)

Fig 17.3 Source: “Saturn and its System” by Richard Anthony Proctor (1865)

Enter Lagrange and Laplace, perhaps the two most renowned French mathematicians of all times. The two ‘science icons’ engaged in a long struggle to try and resolve the paradox while taking care to uphold the sacrosanct Newtonian gravitational ‘laws’. Depending on the source you consult, it was either Lagrange or Laplace who ‘solved the problem’ by using formidably complex equations to show that the apparently increasing gap between Jupiter’s and Saturn’s celestial longitudes was a temporary phenomenon which would eventually reverse course. The gap, it was claimed, would gradually diminish and cancel itself out in the course of about nine hundred years. Our two giant gas planets were not going to bring on the much feared apocalyptic end times after all.

However, it is unclear just how Lagrange and Laplace reached their ‘mathemagical’ conclusions. In academic text books, we may find some dreadfully abstruse computations based on assumptions of how ‘gravitational perturbations’ and ‘tidal friction effects’ might cause those puzzling inequalities. As it is, the Copernican model allows for no plausible explanation as to why Jupiter’s and Saturn’s celestial longitudes would oscillate back and forth, as observed. In time though, and to their great relief, Lagrange and Laplace were eventually ‘proven right’: the apparent, relative accelerations and decelerations of Jupiter and Saturn were observed several decades later to have reversed course:

“In 1773, Lambert used advanced perturbation techniques to produce new tables of Jupiter and Saturn. The result was surprising. From the mid-17th century the Great Anomaly appeared to go backwards: Saturn was accelerating and Jupiter was slowing down! Of course, such behavior was not compatible with a genuinely secular inequality.” “Stability of the Solar System in the 18th century” by Massimiliano Badino

One of the greatest observational astronomers in those days, William Herschel, had also investigated the apparent back-and-forth oscillations of Jupiter and Saturn:

“Herschel describes Saturn’s period as increasing (i.e. Saturn seemed to be slowing down) during the seventeenth century - and Jupiter’s period as diminishing (i.e. Jupiter seemed to be speeding up) and he adds – ‘In the eighteenth century a process precisely the reverse seemed to be going on.” “Saturn and its System” - by Richard Anthony Proctor (1865)

This time, no end-of-the-world scenario was proposed. Nonetheless, as pointed out by a number of contemporary independent researchers, ‘the Great Inequality’ and its corollary, the ‘stability of our Solar System’, both remain unsolved riddles to this day. For instance, Antonio Giorgilli, a veteran Italian expert in this peculiar area of astronomical studies and the author of “La Stabilità del Sistema Solare: Tre Secoli di Matematica” , admits to having no answer to the enigma:

“Su queste basi cercherò di illustrare che significato si possa dare alla domanda: ‘il sistema solare è stabile?’ Quanto alla risposta, non vorrei deludere nessuno, ma sarà: non lo sappiamo”. Translation: “On this basis I will try to illustrate what meaning can be given to the question: ‘is the solar system stable?’ As for the answer, I do not want to disappoint anyone, but it will be: we do not know”.

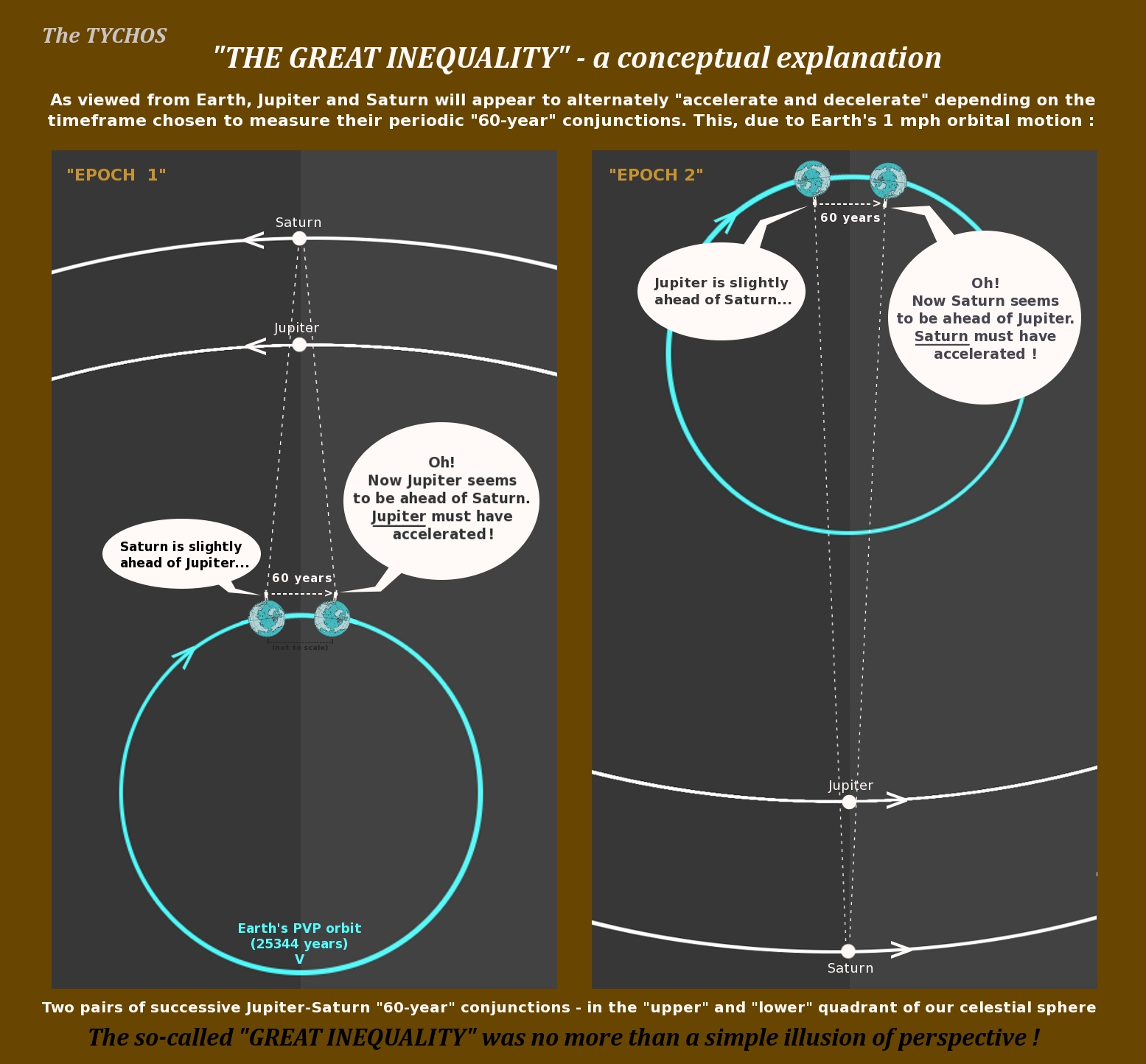

“We do not know”. Indeed not. And chances of figuring it out are virtually nil as long as we base our reasoning on the wrong configuration of the Solar System. We have looked at some of the historical controversies surrounding the ‘mysterious’ motions of Jupiter and Saturn; it now remains to be seen if the TYCHOS model can resolve the riddle of ‘the Great Inequality’ without resorting to gratuitous ‘gravitational perturbations’ or ‘non-gravitational effects’. As you can see for yourself in Figure 17.4, the truth, as is often the case, is quite simple—and yes, you guessed it right: it is Earth’s slow displacement around its PVP orbit that creates the optical illusion that Jupiter and Saturn are alternately accelerating or decelerating. In reality, the two planets move at perfectly constant speeds, just like all the other components of our Solar System.

Fig. 17.4 A conceptual explanation of ‘the Great Inequality’. Two successive Jupiter-Saturn ‘60-year’ conjunctions: in the ‘upper’ and the ‘lower’ quadrant of our celestial sphere. As viewed from Earth, Jupiter and Saturn will appear to alternately “accelerate and decelerate” depending on the timeframe chosen to measure their periodic ‘60-year’ conjunctions. This, due to Earth’s 1 mph orbital motion. The so-called ‘Great Inequality’ is nothing more than an illusion of perspective.

Fig. 17.4 A conceptual explanation of ‘the Great Inequality’. Two successive Jupiter-Saturn ‘60-year’ conjunctions: in the ‘upper’ and the ‘lower’ quadrant of our celestial sphere. As viewed from Earth, Jupiter and Saturn will appear to alternately “accelerate and decelerate” depending on the timeframe chosen to measure their periodic ‘60-year’ conjunctions. This, due to Earth’s 1 mph orbital motion. The so-called ‘Great Inequality’ is nothing more than an illusion of perspective.

1: Whenever (in a certain epoch) Jupiter and Saturn are observed, over a 60-year interval, to conjunct in the ‘upper quadrant’ of our celestial sphere, it will seem as if Jupiter is accelerating.

2: Whenever (in a certain epoch) Jupiter and Saturn are observed, over a 60-year interval, to conjunct in the ‘lower quadrant’ of our celestial sphere, it will seem as if Saturn is accelerating.

This is because, while Earth moves at snail pace around its PVP orbit, Jupiter and Saturn will alternately conjunct as they proceed in the opposite or in the same direction as Earth. So there it is: another fine mess elegantly cleared up by the TYCHOS in a matter of minutes. You can rest assured that Jupiter and Saturn are not afflicted by any fanciful, chaotic perturbations and will not be crashing into the Sun or migrating to other galaxies.

Before we move on, in his paper on the stability of the Solar System, Giorgilli makes another point of paramount interest to the Tychos model:

“The first long-term simulations have been carried out since the end of the 1980s by some researchers, including A. Milani, M. Carpino, A. Nobili, GJ Sussman, J. Wisdom, J. Laskar. Their conclusions can be summarized as follows: the four major planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune) seem to move quite regularly even over a period of a few billion years, which is the estimated age of our Solar System. On the other hand, the internal planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars) present small random orbital variations, in particular of their eccentricity, which cannot be interpreted as periodic movements: we must admit that there is a chaotic component. Not that the orbits change much, at least not in the short term, but there may be, for example, small variations in the eccentricity of the Earth’s orbit that have very significant effects on the climate: the glaciations appear to be correlated with these variations.”

This strongly supports the notion proposed by the TYCHOS that the celestial bodies in our Solar System make up two distinct groups: an ‘inner binary family’ composed of the Sun, Mars, Mercury, Venus and of course the Earth-Moon system, and an ‘outer circumbinary family’ composed of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto.

17.2 Clarifying the 12-year and 30-year periods of Jupiter and Saturn

At this point I would like to take the opportunity to clarify my contention that Jupiter and Saturn have, technically speaking, ‘integer’ periods of respectively 12 years and 30 years, which happen to be perfect multiples of our Moon’s true synodic period (TMSP). As every astronomer will know though, the orbital periods of the ‘Jovian planets’ (from Jupiter to Pluto) are all reckoned to be slightly shorter than integer numbers of solar years. Jupiter, for instance, is said to complete one of its orbits in 11.862 years. Saturn is said to complete one of its orbits in 29.4571 years. This means that, after 12 integer years, Jupiter will appear to have precessed ‘eastwards’ by a small amount. Likewise, after 30 integer years, Saturn will appear to have precessed ‘eastwards’ by a small amount.

Now, if we go to the Tychosium 3D simulator and activate the ‘Trace’ function, we can visualize the peculiar configuration that allows to explain why, geometrically speaking, the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn are actually completed in exactly 12 and 30 integer years. As shown by the screenshots in Figure 17.5, Jupiter will return to the very same point in its characteristic ‘teardrop loop’ after an exact 12 year-period. In other words, Jupiter’s true period is 12 integer years, which corresponds to 150 TMSPs. Likewise, Saturn will return to the very same point in its characteristic ‘teardrop loop’ after an exact 30 year-period. Thus, Saturn’s true period is 30 integer years, which corresponds to 375 TMSPs.

Fig. 17.5 A conceptual explanation of Jupiter’s 12-year cycle and Saturns’s 30-year cycle.

Fig. 17.5 A conceptual explanation of Jupiter’s 12-year cycle and Saturns’s 30-year cycle.

Put differently, since the ‘outer’ planets, Jupiter and Saturn, do not precess ‘clockwise’ along with the ‘inner binary family’ of our system, when seen from Earth their orbital periods will appear to be slightly shorter than they really are. It is therefore correct to say that their true orbital periods are 12 years and 30 years, respectively.

17.3 Saturn’s motions: another Copernican aberration

Did you know that, although the Earth is said by heliocentrists to revolve around the Sun in about 365 days, Saturn can reconjunct with Earth and the same star in only 252 days? This is an observable fact that begs a very good explanation, as I am sure you will agree. For example, the heliocentric Star Atlas simulator shows Saturn on 1 June 1994 and 8 February 1995 facing the same star in the Aquarius constellation (22h56min14s of RA), only 252 days apart:

Fig. 17.6 Screenshots from the heliocentric Star Atlas simulator.

Fig. 17.6 Screenshots from the heliocentric Star Atlas simulator.

The JS orrery, another heliocentric simulator, confirms these positions for the same two dates. One must wonder how the two parallel lines in Figure 17.7 could possibly point to the same star in the Aquarius constellation. To explain away this inconvenient observation, heliocentrists usually claim the stars are so grotesquely far away that the difference between parallel and convergent lines becomes infinitesimal.

Fig. 17.7 Screenshot from the heliocentric JS orrery.

Fig. 17.7 Screenshot from the heliocentric JS orrery.

In comparison, Figure 17.8 shows how the Tychosium 3D simulator depicts the same two conjunctions. As you can see, having completed its retrograde loop, Saturn naturally returns to the very same line of sight, facing the same point in the Aquarius constellation:

Fig. 17.8 Screenshot from the Tychosium 3D simulator.

Fig. 17.8 Screenshot from the Tychosium 3D simulator.

I will leave it up to the reader to judge which of the simulators provides the most sensible explanation for the observed behaviour of Saturn as it returns to the same point in our skies within a 252-day period. Far from imposing my own world view on others, I think it is time for the scientific community and laymen alike to have a rational and honest debate to determine what configuration of our Solar System best fits observable fact.